Energy Musings - May 19, 2025

The International Maritime Organization has proposed rules that combine mandatory emissions limits and GHG pricing for the entire global shipping fleet. The U.S. objected, but it may be a head fake.

IMO Nears Adopting First Industry-wide Carbon Tax

In early April, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), an arm of the United Nations, completed its 83rd Marine Environment Protection Committee meeting. The meeting approved rules combining mandatory emissions limits and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions pricing across the maritime industry. This was the first in any international sector.

The central policy is a penalty of $380 per ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that ships must pay if they exceed a maximum level of emissions intensity. The allowed intensity will become stricter over time on a set schedule. Ships performing under that intensity standard will still have to pay a fine of $100 per ton of CO2 emissions above a second “direct compliance” level. Ships emitting less than this second standard get carbon credits, which can be banked for future use or sold to underperforming ships. The fee structure means only emissions above a specific limit are fined, with emissions under the limit being untaxed.

If the IMO formally approves the recommended rules in October, the scheme will go into force in 2027. It would be mandatory for ocean-going ships over 5,000 gross tonnage, although coastal vessels and workboats are exempt. The ships targeted by the emissions scheme are responsible for 85% of total CO2 emissions from international shipping. Shipping accounts for about 4% of the world’s CO2 emissions and remains one of the most challenging industries to decarbonize.

The meeting was preceded by two working group sessions – one dealt with reducing greenhouse gas emissions from ships, and the second focused on air pollution and energy efficiency of ships. These sessions showcased the international shipping industry's progress since 2019 in cutting emissions.

The meeting in London was contentious and judged by observers as either “a turning point for shipping” or a “shipwreck.” The U.S. delegation withdrew from the meeting. It issued a diplomatic note, reading in part: “The U.S. rejects any and all efforts to impose economic measures against its ships based on [greenhouse gas] emissions or fuel choice." While the media portrayed the U.S. withdrawal as disengagement, it may have been part of the Trump administration’s long-term plan to revive the U.S. commercial shipping industry.

The vote approving the IMO rules was 63 nations in favor and 16 opposed, an 80% favorable outcome. However, only 79 of the 176 IMO member states were present for the vote. The nations approving the measures represent barely over one-third of the member states who presumably will be voting in the fall. Besides the U.S., Russia and Saudi Arabia objected to the proposal.

People pleased with the meeting’s outcome suggest this is a “step in the right direction” to reducing emissions, although only a small portion of ship emissions are subject to a global carbon tax. However, even they acknowledged that the projected emissions reduction of around 10% by 2030 compared to 2008 remains well below the track needed to meet the IMO’s long-term emissions reduction target.

In 2023, the IMO established maritime industry carbon emission reduction targets of 20%-30% by 2030 and 70%-80% by 2040 compared to 2008. This was a dramatic increase from its target set in 2018 of a 50% reduction by 2050. Achieving the new 2040 target would require the average ship to reduce its GHG intensity by 90%.

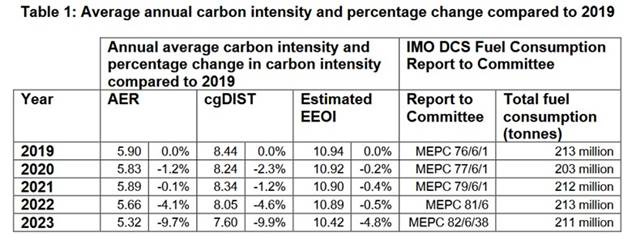

The IMO working group on ship energy efficiency reported the latest data showing meaningful progress. In the table below, the carbon intensity is measured in two ways - annual average supply-based (AER and cgDIST) and demand-based (EEOI) measurements of carbon intensity. Supply-based intensity is down almost 10% compared to 2019, nearly twice the decline of demand-based intensity. Both measures show much greater improvements compared to 2008, -23% for supply-based and -34% for demand-based. Of course, the industry has probably achieved the easiest reductions, meaning the remaining cuts will require more dramatic changes. For example, the industry’s sulfur reduction efforts (IMO 2020) likely explain a significant portion of the carbon intensity reductions experienced as heavy fuel oil consumption has fallen dramatically.

The shipping fleet is progressing in reducing its fuel carbon intensity.

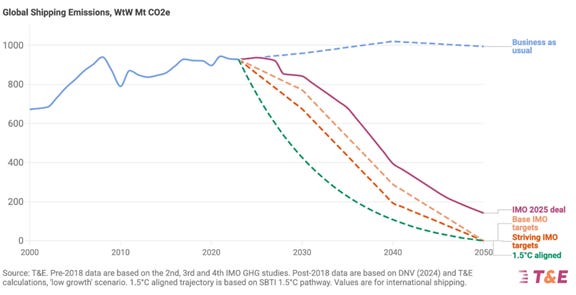

Various scenarios based on ship emission reduction plans are shown in the chart prepared by Transport & Environment. Based on the approved plan and the industry's reaction, we wonder whether reality will come close to meeting these projected emissions reductions. If not, then more drastic actions may be warranted by IMO.

Potential shipping industry emissions reductions.

Did the U.S. use the MEPC 83 meeting to send a message to international shipowners? If so, what is that message? An analysis by Cavalier Shipping showed that the IMO carbon fines and its emissions reduction schedule mean that a medium-range oil product tanker would be subject to an annual fine of $575,000 in 2028, rising to over $3.2 million by 2035 without the shipowner investing in emissions-reduction technology.

They pointed out that international ships that can serve both U.S. commercial and military markets have a new option. The current U.S. Tanker Security Program (TSP), which supports U.S. flag medium-range product tankers, offers a $6 million stipend per vessel in exchange for their availability during national emergencies. By avoiding the IMO carbon emissions fine, the ship would benefit by nearly $6.6 million in 2028, rising to $9 million by 2035. Even with the higher operating costs of more expensive U.S. mariners, this enhanced income stream could result in the reflagging of vessels. The IMO decarbonization scheme may aid the Trump administration’s efforts to grow the domestic commercial shipping fleet. Since building 250 new commercial ships over the next decade will be challenging, adding to the fleet by reflagging international ships may accelerate fleet growth, helping reduce the nation’s national security risk.