Energy Musings - June 16, 2025

The East Coast offshore wind market is in turmoil, which we have covered. Economic challenges are the problem. A UK analysis shows how expense offshore wind is and why subsidies are insufficient.

Offshore Wind Continues To Face Stormy Weather

The Nor’easter spawned by President Donald Trump’s January Executive Order to halt all wind permitting has riled up the East Coast offshore wind market. While much of the recent drama has focused on Empire Wind's status, the 815-megawatt (MW) project off New York Harbor, there is turmoil worldwide. We covered the latest East Coast saga in Empire Wind Sued Over Lease And Permit Approval, Energy Musings, June 9, 2025. (https://energymusings.substack.com/p/energy-musings-june-9-2025)

The most recent flotsam from the East Coast storm is Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind, the developer of a 1.5-gigawatt (GW), 200-wind-turbine project, petitioning the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities to withdraw from the Offshore Renewable Energy Certificate framework established in 2021. The developer cited a range of issues influencing its decision, including increased costs for steel and manufactured components, high interest rates, supply chain disruptions, and President Trump’s executive order.

Last January, Shell plc exited the joint venture it formed with French electric utility company EDF to build the Atlantic Shores project. Its subsidiary, Shell New Energies US LLC, remains a partner with EDF’s EDF-RE Offshore Development, LLC, in the holding company formed for all its offshore East Coast projects. Shell wrote down its Atlantic Shores investment by $980 million, while EDF did the same in February.

In a court filing by a group of state attorneys general against the Trump administration’s January decision pausing offshore wind permitting, it was disclosed that SouthCoast Wind will not be able to meet the June 30 deadline to negotiate a power purchase agreement with Massachusetts. SouthCoast Wind’s CEO says the project could be delayed for two years. That is a blow to the state’s clean energy plans, but may also explain why Governor Maura Healey has announced support for nuclear power while also seeking ways to reduce resident electricity bills.

The outlook for offshore wind in Europe is mixed. Some developers are shutting down projects and not participating in offshore wind auctions because subsidies are not guaranteed or high enough. In the UK, Danish developer Ørsted announced that adverse economic developments forced it to halt its 2.4 GW Hornsea 4 wind farm in the North Sea. That follows Swedish developer Vattenfall stopping work on its 1.4 GW Norfolk Boreas wind farm in 2023 for similar reasons.

Elsewhere in Europe, the Netherlands has been examining how to reintroduce subsidies in its next offshore wind tenders. The absence of subsidies has forced the country to delay its goal to reach 21 GW of offshore wind capacity by two years to 2032.

In January, Denmark announced it was reworking its offshore wind tendering process because no one bid in its last tender, which did not offer subsidies. The new scheme being contemplated considers the bids received in a tender to determine the amount of government subsidies that will be provided. According to media reports, the government is considering subsidies of up to 55.2 billion Danish crowns ($8.32 billion) over 20 years. The government is planning three tenders with a combined 3 GW of capacity this fall, two additional tenders in early 2026, and one in the fall of 2027. The projects awarded under these tenders are projected to come online by 2032 and 2033.

Around the world, we see offshore wind developers exiting projects. Because of unsustainable costs, Norway’s Equinor has withdrawn from offshore wind projects in Vietnam, Spain, and Portugal. Likewise, Shell sold its interests in projects in South Korea, Ireland, and France, besides Massachusetts, when it cancelled its interest in Atlantic Shores.

The Problem

What is wrong with offshore wind? In a word: uneconomic. The offshore wind business model prospered during the years of cheap money. Renewable energy projects are inherently low-return businesses, impacted by the time value of money. They require substantial investment upfront, with revenues not arriving for years, but then continuing for years, usually at the fixed price agreed initially. These projects generally earn returns on equity in the low- to mid-single digit percentages. Developers boost their returns on equity by adding significant amounts of debt. It’s called leverage.

The problem with this business model is that this financial structure can be quickly upended when interest rates rise. Terrence Keeley, chairman and CEO of 1PointSix, told the audience at the Future Energy Forum conference in May, co-sponsored by the National Center for Energy Analytics (we are a senior fellow), that interest rates going from 0% to 5% can triple the cost of capital on renewable projects. If you haven’t factored that into your project’s economics, it is a disaster.

A 2023 Time magazine article stated, “A 2020 analysis from the International Energy Agency shows that a 5% rise in interest rates would increase the levelized cost of electricity from a natural gas plant only marginally, while it could increase the cost of electricity from wind and solar by a third.” We believe that the writer is not financially savvy. The difference between 0% and 5% is magnitudes greater than increasing interest rates by 1.05%. We wonder if the author meant a five percentage point increase rather than a 5% increase in the current interest rate.

The Time magazine writer further noted that the 2023 report from the investment firm Lazard, a long-time chronicler of the levelized cost of energy (LCOE), highlighted how the cost of renewable energy had risen. In 2021, Lazard estimated that the average LCOE for utility-scale solar power was $38 per megawatt-hour. In 2023, the cost estimate jumped to $60, a 58% increase in two years. Lazard said wind had “seen a similar increase.” The LCOE increase was directly attributed to the higher-interest rate environment. The low-interest rate world no longer exists.

Subsidies Hurt UK Ratepayers

Regulators around the world have ignored this new interest-rate environment. A new report from David Turver of Eigen Values shows how UK energy regulators setting renewable energy subsidies are basing their decisions on failed analyses. Turver’s analysis is based on the latest data from the Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) seventh carbon budget, which was released in March. He was able to update his calculations after the CCC released its methodology for setting the Contract for Difference (CfD), the UK’s subsidy mechanism for renewable energy.

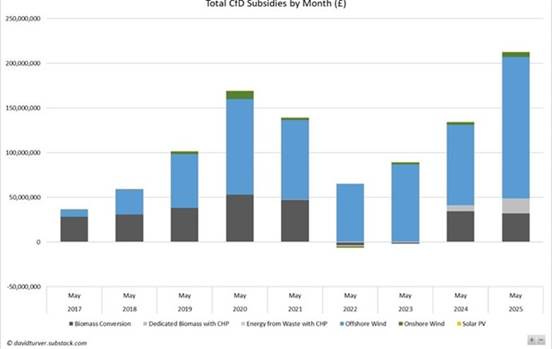

In another report from Eigen Values, Turver showed the magnitude of the CfD paid each May from 2017 to 2025. The dramatic increase in recent years explains why UK ratepayers are outraged. The May 2025 CfD payment for offshore wind is twice the previous largest payment in May 2020.

Current UK offshore wind subsidies hit a record cost.

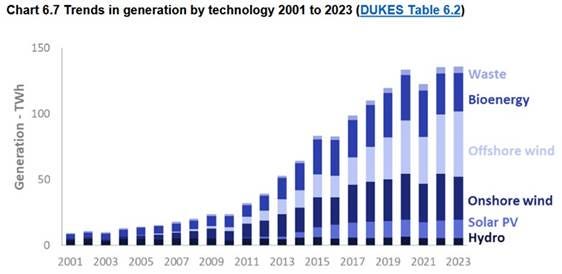

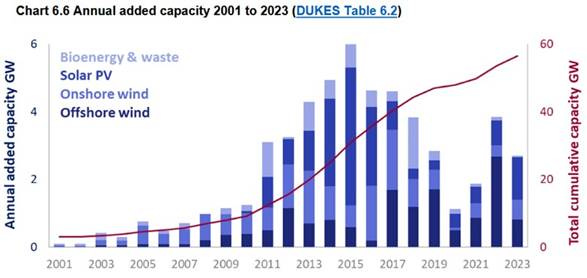

The following two charts show IK electricity generation and annual generation capacity added by technology for 2001-2023. They convey the continued growth in capacity and output. The latter is what drives the CfD payments.

UK renewable power output was flat from 2020 to 2023 due to the weather.

The UK government noted the variations in the weather on renewable output. Although renewable generation capacity grew significantly during 2013-2019, it fell sharply during the pandemic years. The subsequent capacity additions recovery was muted, likely due to the industry’s changed economics. Despite the capacity growth, total output was flat from 2020 to 2023 due to weather variability. This points up a weakness of renewable energy and why people should view claims about capacity additions skeptically.

UK renewable generating capacity continues to grow.

Turver’s first report showed some of the fallacies of the CCC in setting CfDs that reflected unrealistic economics for offshore wind. He based his comments on studying the latest Electricity Generation Costs. As he wrote in an op-ed published by The Telegram, “The new report showed that the estimated levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for wind had fallen from £57/MWh in the 2020 report to £44/MWh in the latest [2023] publication.”

Turver found that when comparing the data from the two 2025 CCC reports, the LCOE of offshore wind was expected to decline. The decline was driven by an increase in the expected capacity factor (output related to total capacity) from 51% to 61%. That means it is spreading the high fixed costs of offshore wind farms over more generated electricity units, bringing the LCOE down. This assumption contrasts with the latest 5-year record of a 41% capacity factor.

He further noted CCC’s assumed 81% reduction in the estimate for infrastructure costs for a 1-GW wind farm built in 2025. The decline is from £344.8 ($469.0) million to £64.3 ($87.5) million. The analysis also assumes that the construction and capital costs remain flat. In addition, they assume a 30-year life for offshore wind farms, in contrast to the 25-year life assumptions of many wind farm developers. The challenge to that assumption is that Germany is dismantling its first offshore wind farm after 15 years of use.

There is a significant issue with the CCC’s assumption about the cost of capital. Turver notes that its 2016 report assumed a cost of capital of 8.9%. By 2020, that cost had fallen to 6.3%. Capital cost hurdle rates are usually set as a factor above the average of 10-year and 30-year bonds. Generally, that factor is 6.5 percentage points. When Turver wrote his op-ed, that factor applied to the then-current interest rates yielded a cost of capital of around 11%.

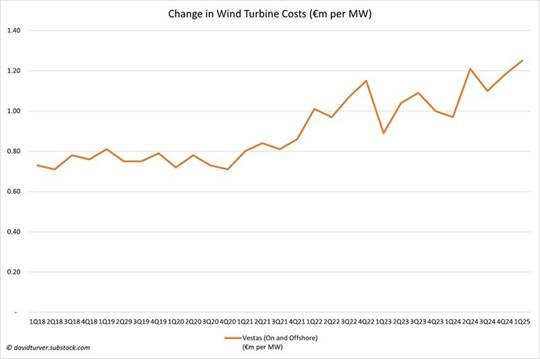

He then looked at what had happened to turbine costs based on reports from Siemens and Vestas, two of Europe’s largest suppliers. They report that the cost of wind turbines had increased by 47% between the end of 2020 and 2022.

Turver ran a sensitivity analysis based on the lower capacity factor, the higher cost of capital, the higher cost of construction, and a reduced wind farm life. The net effect is to push up the CfD estimate to £131.05 ($178.27) per megawatt-hour (MWh) from the £44 ($59.85)/MWh estimate of the CCC.

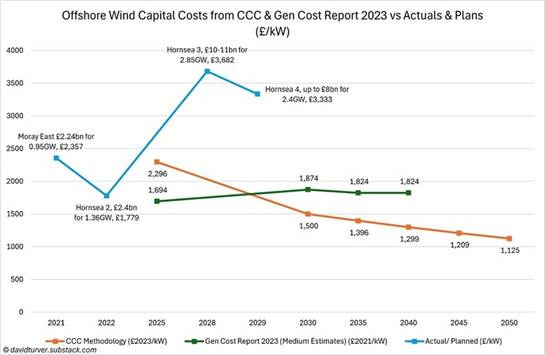

With the release of the latest CCC methodology report, Turver could update his estimates and compare them against actual data. Here is his updated chart of the cost of capital analysis. It shows the CCC estimates to 2050, the generation report estimates, and the actual data from offshore wind projects. We would point out that the last data point shows the cost of capital for the Hornsea 4 project, which Ørsted just shut down for being uneconomic.

Offshore wind is proving to be more costly than expected.

Another updated Turver chart shows the cost of offshore wind turbines. The data is based on quarterly reports from Vestas. Turver noted that turbine costs had risen 47% between the end of 2020 and 2022. There was a sharp drop in reported costs at the start of 2023, but then the upward trend resumed, putting the price at the beginning of 2025 above the 2022 peak.

Offshore wind turbine costs are continuing to increase.

Turver’s final chart shows the CfD awards – the guaranteed price from which subsidies are paid – for fixed and floating offshore wind projects compared to CCC’s LCOE estimates. If we only look at the fixed CfD awards, the 2024-2025 award amounts are close to the estimated LCOEs, but the 2028 award is about double the estimate. Floating offshore wind CfDs are well above the CCC estimates, reflecting the significant cost differences between bottom-supported and floating offshore wind.

These differences highlight the unrealistic assumptions built into the UK government’s estimate of the cost of offshore wind. That is important because offshore wind is being heavily counted on to reduce electricity costs and help to meet the UK’s net-zero emissions targets.

Actual offshore wind costs are well above regulator estimates.

In contrast to the U.S., where limited liability companies conduct offshore wind projects and most renewable energy projects, many UK projects are done by public companies or subsidiaries required to file financial statements. The documents submitted to public utility regulators to justify power purchase agreements are heavily redacted, as the companies want that information to remain confidential. We hope U.S. utility regulators receive unredacted information and apply rigorous analyses. They are the last line of defense for ratepayers from paying obscenely high electricity rates.

Solving the Problem

Turver’s analysis explains why offshore wind projects are being cancelled and why bidders for new ones are demanding substantial subsidies. Costs for these projects have soared. Subsidies are the only way developers can overcome the flaws in their business models. Maybe it is time for offshore wind farm developers to reconsider their business models and, if possible, find better ones. On the other hand, perhaps they and their promoters should be more honest about what their electricity will cost the ratepayer, rather than trumpeting the canard that wind power is cheap.

Another issue UK wind is experiencing, but not covered here, is the cost of switching off wind turbines because they generate more power than the grid can accept. According to data from the grid operator, it needed to switch off UK wind farms 13% of the time during 2024-2025 at a cost of £2.7 ($3.7) billion. That expense is passed on to ratepayers, further escalating their power bills.

Offshore wind is expensive, as Turver’s analysis shows. Furthermore, it does little to reduce carbon emissions because of the need for backup power. It is time for energy realism to drive government policy.