Energy Musings - September 27, 2023

All eyes are focused on rising oil prices. Fear is they will boost gasoline pump prices and inflation. The real economic worry, not only here but globally, is declining diesel inventories.

Gasoline Prices Less A Problem Than Diesel Inventories

Economists and investors are closely watching rising oil prices, wondering how high they may go after crossing the $91-a-barrel WTI futures threshold. That marks a 20% rise over the last 60 days. Over the same span, U.S. gasoline pump prices rose only 9%. Their rise was held down by the end of the summer driving season. But the bigger problem for the economy, not only here but globally, is the increase in diesel prices in response to a tightening supply situation. U.S. diesel prices increased 22% in the last two months, and they may be about to soar.

Diesel prices are climbing heading into winter as demand rises and supplies are constrained. This is a potential economic disrupter.

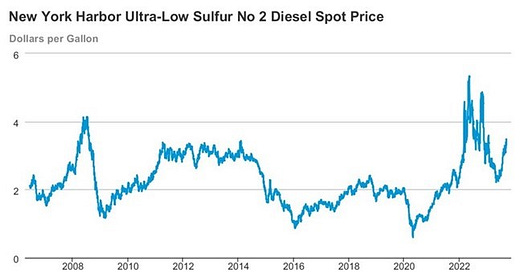

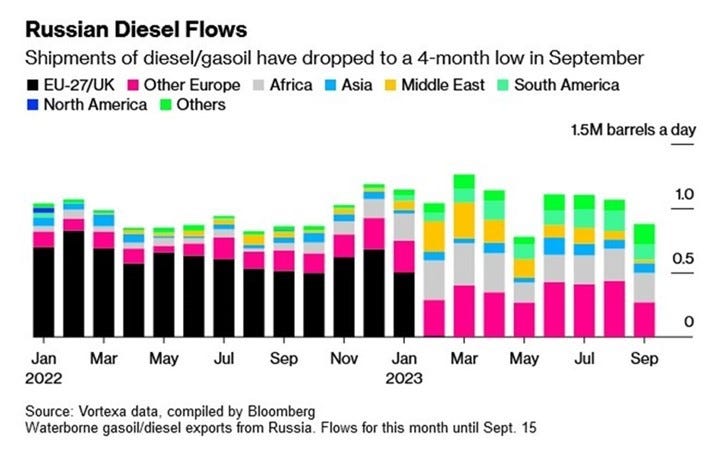

As the chart shows, New York Harbor diesel prices spiked to a modern-day high in the months immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The war prompted a European energy crisis as many of the continent’s economies were dependent on Russia for their natural gas, crude oil, and diesel fuel supplies. Europe was thrown into disarray as fuel supplies were restricted and Western governments retaliated by putting embargos in place on the purchase of Russian energy supplies. The embargo created logistical challenges for European fuel buyers, but they found ways to purchase oil and refined products from other suppliers who were buying and refining Russian crude oil.

As the Energy Information Administration chart shows, from May 2022 to May 2023, New York Harbor diesel prices fell by 50%, falling back to where they had been before the run-up in anticipation of the Russia/Ukraine war. But since the May low, the diesel price has climbed by 50%, bringing it back to levels last seen in 2010-2014 before the 2022 war-driven spike.

Several factors are driving the global diesel market, and their strength and speed of development could be the difference between a sharp spike in diesel prices and a slow climb higher. Certainly, at this time of the year, as we head into winter and seasonal demand ticks up, supply and demand balances become critical.

The production cutbacks by Saudi Arabia and Russia, which will last through the end of 2023, are an important driver for higher diesel prices. Those two countries have chosen to concentrate their production cuts on those oils that contain the most diesel fuel potential. That means refineries can extract a higher percentage of diesel from those specific crude oil barrels than from others, enabling them to build diesel inventories faster. Since there is no guarantee Saudi Arabia and Russia will restore their output cuts when 2024 arrives, this crude oil quality issue could continue to impact diesel availability throughout the winter.

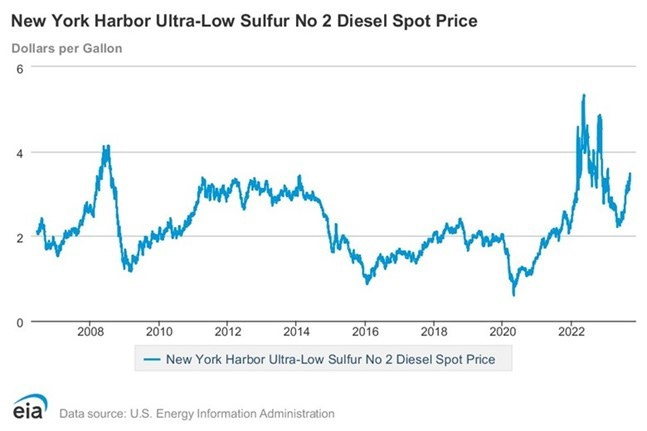

A second factor is the shortage of global refinery capacity to produce diesel and other refined petroleum products. During the pandemic, the oil industry shut down many small and unprofitable refineries or converted them to produce sustainable aviation fuels. Many new refineries have yet to start up, so global capacity is down just when demand is growing heading into winter. Refineries can operate at higher utilization rates for longer, but they risk accidental shutdowns, and when regular maintenance is needed, it may take longer, extending the downtime and limiting building diesel supplies.

Closing unprofitable refineries before new ones start up has reduced industry capacity that impacts global refined product inventories.

Additionally, hot summer temperatures forced many European and North American refineries to run slower, thus diesel stockpiles failed to grow as normally happens heading into winter. Refiners were also pressured to emphasize the production of gasoline and jet fuel over diesel this summer, further limiting the growth of diesel inventories.

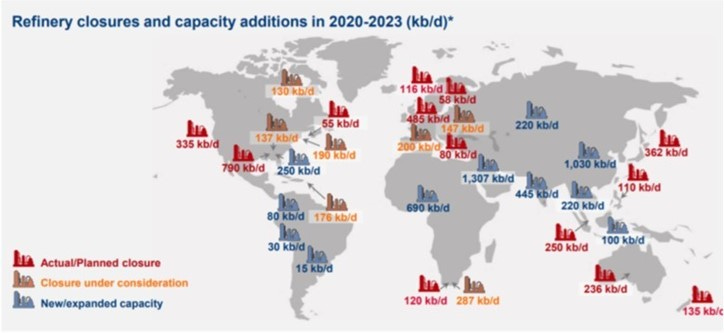

Russia has also decided to become more aggressive and use its diesel exports as an economic weapon. Russia announced a one million barrels a day embargo on diesel exports. It also restricted 500,000 barrels per day of gasoline exports, but European countries rely on diesel for a greater amount than gasoline. Russia instituted these embargos to help contain their domestic market prices and to create further logistical challenges for European allies of Ukraine. Oil traders are not sure how much of the embargoed diesel and gasoline supplies will leak into international markets, but based on the leakage in response to the European Union’s crude oil purchase embargo, they believe a meaningful portion will make it. Depending on the veracity of this assumption, diesel prices might only climb further rather than spike higher.

Russia diesel supplies found other markets in 2023 but its new embargo create problems globally for supplies.

The chart from Bloomberg showing the monthly destinations for Russian diesel oil highlights how volumes shifted significantly once the European Union implemented its ban on buying Russian oil and refined products in January. As oil is fungible, it is not surprising that those non-European destinations in 2022 suddenly grew in importance for Russian output. The diesel supplies previously flowing into those markets were suddenly diverted to Europe. This fungibility is why traders are confident that a significant amount of the embargoed Russian diesel will leak out to foreign markets.

A final consideration in the global diesel market conundrum is how China is managing its oil industry. Earlier this year, it was thought China’s oil consumption was experiencing a record rebound from its Covid-19 closure. However, although consumption was higher, it turned out that the government was using low crude oil prices to stockpile the record oil imports for when prices rose. Now that oil prices are substantially higher, expectations are that China will begin releasing those stockpiles to ease domestic gasoline and diesel prices in its economy and to keep refineries operating to export products to boost government revenues. Therefore, it is possible that as we head into winter, more Chinese diesel will be flowing into Asian markets easing the near-term upward price pressure. If Chinese demand continues to grow in 2024, the tight supply situation will support higher diesel prices and likely push them up further.

The challenge in the U.S., like elsewhere, is low diesel inventories heading into winter. The following chart shows the weekly inventory story for low-sulfur diesel that was mandated for the over-the-road market in 2010 and then for all uses – off-road, railroad, and marine – in 2014. Since early 2022, the low points in inventory were last seen in 2014 when the market expanded, and demand was inflated. Prior inventory lows were associated with the end of winter and not the start as we are now confronting. That has ominous implications for future diesel prices.

Distilate inventories are at the lowest levels since 2010-2014 but this is heading into winter and not coming out.

It is important to understand the role diesel fuel plays in economies. It is the predominant fuel of the heavy-duty transportation sector – trucks and trains. That is how goods move from factories to stores. It is hard to think of any product not touched by diesel vehicles. From food to raw materials to finished goods, it is hard to think of anything in our everyday lives that is not touched by diesel power. Diesel is interchangeable with home heating oil, which is why we focus on distillate inventories. An abnormally cold winter could draw some of the diesel inventory into servicing that market.

If oil is the economy, then diesel is the workhorse. Higher diesel prices will be passed on to consumers. The Wall Street Journal reports that some long-haul food trucks are charging retailers a surcharge for expensive diesel. That will only get worse as diesel prices climb. It will spark greater inflation, inflicting harm on our economy, businesses, and families.