Energy Musings - October 28, 2024

California regulators are scrambling to adjust their vehicle emissions reduction plans to deal with market realities. Ending diesel trucks is not about to happen on the state's timetable.

California’s EV Mandate Confronts Reality

California has a legal requirement to eliminate its carbon emissions. It has been a national leader in this effort, and several other states follow its lead. Regarding eliminating emissions from light-duty vehicles, 17 states plus the District of Columbia follow California’s rules. However, only 10 states follow its heavy-duty truck emission mandate.

The state is having problems implementing its latest vehicle emissions rules. Amazingly, California’s followers are now acknowledging its problems. As they see the problems and the harm the rules are creating for their citizens, they are breaking away from the zero-emissions parade. New Jersey was first. Oregon, Massachusetts, and New York are mulling following New Jersey.

California’s War to End Carbon Emissions

Let’s look at the history and current emissions landscape to understand why the tide suddenly seems to be going out rather than sweeping up more state followers.

Here are California’s original greenhouse gas (GHG) emission targets.

• By 2010, reduce GHG emissions to 2000 levels.

• By 2020, reduce GHG emissions to 1990 levels, and

• By 2050, reduce GHG emissions 80% below 1990 levels.

Over the years since these targets were introduced, California governors enacted Executive Orders restating and amplifying their GHG targets. For example, an order established a new 2030 GHG emission reduction target of 40% below 1990 levels. The target was established to check that California was on track to meet its 2050 80% reduction target. The interim target’s impact puts increasing pressure on regulators and vehicle manufacturers to move faster on their carbon-cutting steps.

Another Executive Order established “a goal of at least 5 million zero-emission vehicles (ZEV) on California roads by 2030.” Another order set a new statewide goal of carbon neutrality as soon as possible, but no later than 2045, and maintain net negative emissions.

At mid-year 2024, California has 1.8 million ZEVs on its roads, leaving it 3.2 million units short of its target. Over the next five and a half years, California will need to sell nearly 600,000 ZEVs annually to reach its target. Last year, there were 441,283 EVs of all types sold according to the California Energy Department. Among that total, 63,496 were plug-in hybrids and 3,119 were fuel-cell cars with the remainder being battery-only electric vehicles. Thus, the annual sales pace must increase by nearly 36%.

There is no question that California is moving quickly to cut its emissions. Interestingly, the California Air Resources Board (CARB), which is responsible for implementing the state’s Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) regulations, said last year that it did not require waivers from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Air Act provisions to make changes to its ACF rules.

In October 2023, the California Trucking Association sued CARB over its plans to enforce its electric truck rules. The lawsuit said, “while CARB may claim otherwise, ACT [Advanced Clean Trucks] cannot be enforced until such waiver is granted.” The CTA also said, “CARB is prohibited from enforcing its own emissions standards in the absence of an EPA waiver.” Not surprisingly, CARB suddenly filed for an EPA waiver, but without making the filing public.

One ACT rule deals with electrifying California’s drayage trucks at the state’s ports. According to ACT, effective January 1, 2024, no non-electric drayage trucks could be registered for port work. While the EPA has yet to approve a waiver, the statistics of electric drayage trucks show progress.

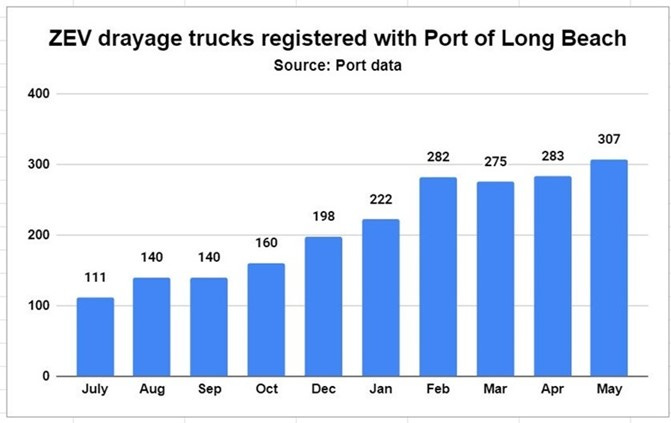

In early October 2023, the drayage registry for the Port of Long Beach, the second largest U.S. cargo port, showed 218,440 trucks on the list, according to FreightWaves.com. In July 2023, the first month the port reported data on drayage truck moves, there were 111 zero electric vehicles (ZEV) active. By October, the number climbed to 160. The port operational data showed that in July, 0.5% of all drayage truck moves were conducted by ZEVs, but by October that share was up to 0.86%.

Electric trucks at Long Beach increased early in 2024.

Source: FreightWave.com

With the January 2024 registry cutoff date imminent, it was not surprising that the number of drayage ZEVs increased. Five months into 2024, the number of ZEVs at Long Beach increased to 307 from 198 in December 2023, a 55% jump. However, in May, despite all the financial incentives to aid truck purchases, the number of ZEV truck moves in the Port of Long Beach was only up to 1.48%. Internal combustion engine (ICE) trucks continue to perform virtually all the moves at the port despite electrifying this fleet representing one of CARB’s highest priorities.

The existing ACF rules are designed to phase out all drayage trucks with a model year before 2010. All Class 7 and 8 diesel drayage trucks were supposed to leave the market by January 1, 2024. The rules specify that a drayage truck must be removed from the system under one of two scenarios. It must be removed when it reaches 18 years of age or 800,000 miles of use, or if its 800,000 miles are met within 13 years. In other words, if a truck racks up 800,000 miles in 11 years, it can continue to operate until the 13-year mark. However, once an older truck reaches 800,000 miles, it must be removed regardless of age.

The Port of Long Beach has a program to build electric charging stations to incentivize the addition of ZEV drayage trucks. The funding comes from a $10 tax on 20-foot containers moved by non-ZEV trucks while exempting ZEV loads. So far, the port has raised $70 million. We doubt Californians or Americans have any idea that the cost of their merchandise is boosted by this tax.

Ending Diesel Trucks in California

The push to close out the diesel truck era in California is running into market problems. ZEVs are much more expensive than ICE trucks. In most cases, ZEVs cost twice as much as a diesel truck. According to the American Truck Dealers, a typical electric Class 8 truck costs roughly $400,000 while the average cost for a comparable diesel-powered vehicle is $180,0000. In many cases, the price difference can be up to three times the cost of a diesel truck. Therefore, when talking about vehicles costing upwards of $400,000, the $40,000 federal tax credit does little to close the cost differential.

There are also major operational problems such as charging ZEV trucks and their range. Heavy-duty ZEV trucks have a range of 150 miles on average compared to 1,000 to 1,500 miles for a diesel truck. The charging time for a ZEV truck can be 90 minutes, severely diminishing their usefulness for long-distance transportation, thereby limiting them mostly to local delivery services. Then there is the problem of finding a charging station.

Ryder System released a study comparing the total cost to transport (TCT) for ZEV trucks versus diesel trucks. It was “based on representative network loads and routes from Ryder’s dedicated fleet operations, which includes more than 13,000 commercial vehicles and professional drivers. It factors in the cost of the vehicle, maintenance, drivers, range, payload, and diesel fuel versus electricity, while also accounting for EV charging time and equivalent delivery times. The analysis also assumes the accessibility and use of the fastest applicable commercial vehicle chargers – though this network infrastructure is not yet built out.” That was a very comprehensive methodology.

The study compared the TCT on a one-to-one basis for diesel and ZEV transit vans, straight trucks, and heavy-duty tractors. Ryder based the study on its overall universe of trucks but also on several specific markets, California being one. The following are the conclusions for California.

• “A light-duty EV transit van (Class 4) shows an estimated annual increase in TCT of approximately 3% or nearly $5,000. While vehicle cost increases 71% and labor increases 19%, partially due to more time required for EV charging, fuel versus energy costs decrease 71% and maintenance cost decreases 22%.

• "For a medium-duty EV straight truck (Class 6), the annual TCT increases to approximately 22% or nearly $48,000. The vehicle cost increases 216%, which is only partially offset by a 57% savings in fuel versus energy and 22% savings on maintenance.

• “And, for a heavy-duty EV tractor (Class 8), the annual TCT increases by approximately 94% or approximately $315,000. The equipment cost is the largest contributor, representing an increase of approximately 500%, followed by general and administrative costs that increase approximately 87%, and labor and other personnel costs that increase 76% and 74%, respectively. Fuel versus energy savings are approximately 52%. This assumes delivery times equivalent to a diesel vehicle and factors payload and range limitations as well as EV charging time – all of which requires nearly two heavy-duty EV tractors (1.87) and more than two drivers (2.07) to equal the output of one heavy-duty diesel tractor (which requires 1.2 drivers on average).”

The high cost of ZEV vehicles across the board is a major profitability problem for trucking companies being forced to buy and operate ZEVs. They save money using electricity versus diesel fuel, but the other costs destroy that economic advantage.

The most damaging comparison was with heavy-duty trucks that require nearly two ZEV tractors, and two drivers, to haul the same load as a diesel truck. For an industry struggling to find people willing to work as over-the-road truck drivers, a switch to ZEVs would create serious staffing challenges along with operational problems.

“While Ryder is actively deploying EVs and charging infrastructure where it makes sense for customers today, we are not seeing significant adoption of this technology,” says Robert Sanchez, chairman and CEO of Ryder. “For many of our customers, the business case for converting to EV technology just isn’t there yet, given the limitations of the technology and lack of sufficient charging infrastructure. With regulations continuing to evolve, we wanted to better understand the potential impacts to businesses and consumers if companies were required to transition to EV in today’s market.” (Emphasis added.)

The outcome of the Ryder analysis is not supportive of an impending and rapid transition from diesel to electric trucks. Therein lies the challenge facing CARB and the other states embracing California’s ACT rules. CARB’s ACT rules are forcing dealers to limit the sale of diesel pickup trucks because they will not be able to meet their state fleet emission rules. Therefore, a diesel pickup truck can only be purchased if a ZEV pickup truck is sold. This is rationing.

To overcome the problems truck engine manufacturers face, CARB has proposed amending their 2023 agreement. The proposed ACT amendments would help companies more quickly receive emissions credits when they sell a ZEV and provide a grace period for rule violations.

A manufacturer would receive credits when the truck is delivered to a California dealer or truck upfitter, who adds components and accessories before sale, rather than when it reaches the final customer. That would significantly shorten the waiting time for the credit, which now can be extended by more than a year. Credits can be sold and turned into cash for the manufacturer.

The second rule modification may be more significant for the ZEV market in California. CARB is now proposing that companies have three years to make up for missing their ZEV requirements in any given year. Theoretically, this would stop ACT from forcing diesel vehicle sale rationing until the charging challenges are overcome and ZEV costs moderate.

Politicians in states where climate change mandates are pushing up electricity prices are feeling the heat in this election cycle. As a result, some of them are beginning to balk at following California’s electric truck, fearing additional public pushback. Four of the 10 states following California’s ZEV mandate are rethinking that support.

New Jersey is contemplating giving truck manufacturers a break from selling ZEVs. Democratic legislators introduced two bills to push back the state’s compliance with California’s ACT rule by two years. They cited the unavailability of ZEVs as well as an adequate charging infrastructure. “The state is just not ready,” said New Jersey Senate Transportation Chair Patrick Diegnan.

Officials in Oregon, Massachusetts, and New York are proposing actions to slow down the push for ZEV trucks. In Oregon and Massachusetts, officials are delaying following California’s clean diesel rule, citing a shortage of ZEVs that meet those specifications. They also cited the lack of California’s EPA waiver as a reason to delay.

Separately, New York and Massachusetts officials are creating a special exemption from the rules for snowplows and street sweepers because city leaders say they can’t find cleaner models. Given the recent battery fire of an emergency vehicle parked in a firehouse that resulted in the total destruction of the facility, officials must worry about more electric vehicles in their government fleets.

The comedy is all the finger-pointing underway about these backtracking on ZEV rules in the face of market realities. As we indicated above, CARB is amending its ACT rules to try to sustain the ZEV momentum. The lack of the EPA waiver for the ZEV drayage rules must be troublesome for CARB officials. However, since the rules were expected to begin on January 1st, manufacturers shifted production and deliveries while buyers placed orders last year. That momentum is suspended, but it has created ripple effects elsewhere.

“Vehicle manufacturers want to sell as many [zero-emission vehicles] as possible," Jed Mandel, president of the Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association, told Politico California. "But, given the lack of infrastructure and cost concerns, customers aren’t buying them. As a result, manufacturers are limited in the number of traditional diesels they can sell."

Given the reality that California’s rules require a percentage of all truck sales to be electric, manufacturers are sending their ZEVs to the state. Additionally, they are limiting the number of diesel trucks they manufacture.

Not surprisingly, environmentalists see the market reality being manipulated by diesel truck manufacturers. Whenever bad policies and regulations create market disruptions, it is never the fault of the politicians’ policies or the regulators’ rules, it is the price-gouging, selfish industry CEOs.

If the problem is that ZEVs are priced too high, it must be the manufacturers’ problem. Craig Segall, a former top official at CARB and now vice president of Evergreen Action, sent a letter to California Attorney General Rob Bonta last week calling for the investigation of truck manufacturers’ pricing and production strategies. “I think they would very much prefer a world in which they can invest less in cleaning up their combustion fleet and do the zero-emission transition at whatever pace they prefer,” Segall said.

Earlier, CARB Executive Officer Steve Cliff questioned the diesel manufacturers’ arguments. He said California’s emissions reduction targets aren’t limiting 2024 diesel engine sales. The companies can buy emissions credits instead of selling ZEVs, which would allow them to continue selling diesel trucks. In Tesla’s surprising third-quarter earnings report, it reported revenue from emissions credits it sold to other companies of $739 million, well above analysts’ expectations for $539 million, and a 33% year-over-year increase.

Ray Minjares, heavy-duty vehicles program director at the International Council on Clean Transportation, probably summed up the situation the best. He pointed out that manufacturers are balking, maybe because they understand their customers and the market better. But he also took CARB officials to task for assuming the ZEV sales requirements would bring lower vehicle prices. Mythical thinking.

Minjares assessed the situation. “To put it bluntly, the manufacturers have taken control of the situation and determined what market they want to see.” We doubt the manufacturers “determined” the market but rather they understood better the market destined to be created by pushing a not-ready-for-prime-time technology. Manufacturers understood the economics of ZEVs versus diesel trucks laid out so well by Ryder in its analysis released last May. Ryder’s analysis pointed out that ZEVs are likely to be a niche market – local delivery services. Forcing ZEVs into the heavy-duty truck market will drive up inflation and create huge supply train problems further creating economic problems. Ending the diesel truck era will have to wait.