Energy Musings - October 1, 2023

Two stories: Block Island Wind's latest output data shows it continues to under perform. Omen for new wind farms? Energy topped September's and 3rd quarter's performance. More to come?

What’s Going On With Block Island Wind?

The nation’s first offshore wind farm, Block Island Wind, continues to underperform its avowed output projection. The latest monthly data from the Energy Information Administration for July showed the wind farm produced 3,289 megawatt-hours (MWh) of power. That output represented 55% of the average July output for 2017-2022. Since that span includes the July 2021 output, when major maintenance necessitated four of the five wind turbines be shut for extended periods, we adjusted the average by excluding that month’s output. Thus, this July’s output was only 48% of the adjusted monthly average. Is it all due to maintenance or are there other operational problems?

We were puzzled by the absence of any data for April. We were told that there was a notice to mariners from Ørsted, the wind farm’s owner, that the wind turbine closest to Block Island needed major repairs and would be shut down for much of the summer. The blades needed to be removed and the turbine’s nacelle disassembled to allow replacing the coils inside.

The six months of Block Island Wind’s 2023 output data totals 42,075 MWh, almost exactly half the full-year output for repair-impacted 2021, which totaled 84,208 MWh. We have reached out to Ørsted for an explanation of why there is no data on the EIA website for April output. We were told they would get back to us. Besides an answer to that question, we will be interested in seeing the August data as it was cooler and stiller than we remember from last year.

If the August through December output matches the best year for Block Island Wind (2019), this year’s output would still be less than 90,000 MWh. If we then add in the best April output (2020) the wind farm will reach about 102,000 MWh. Will that be considered a good output or a bad one?

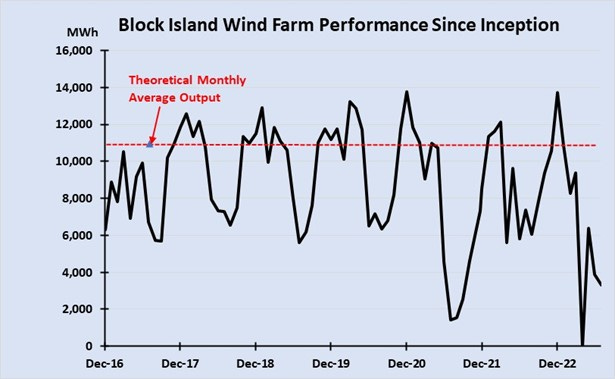

Here is the monthly output of Block Island Wind from the start of operations in January 2017 through July 2023. The chart demonstrates the value of the wind farm’s production in helping the New England grid’s winter electricity supply. In the winter, natural gas barely meets half the system’s power generation needs as supplies are diverted to satisfy home heating demand. Natural gas supply is plentiful during the summer and provides well over half the fuel needed to generate the grid’s output. As a result, the low offshore wind output during the summer months is not a supply issue.

Block Island Wind has underperformed its promised power output each year since it began operation.

While focusing only on annual data, the climate reporter for The Providence Journal calls any year that Block Island Wind generates over 100,000 MWh of power a success. According to an article he wrote back in April, he claims, Block Island Wind has been exceeding output expectations by producing more than 100,000 MWh each year. He claims that at the time wind farm was being built, expectations were that the turbines would achieve a 40% capacity factor, or the amount of wind power generated over the totality of 24 hours a day for 365 days a year. We are not sure where he got that estimate, other than by rewriting the history of the wind farm to claim it is successful to counter critics who say it has not been as productive as expected. When the local media is ‘bought and paid for’ by the offshore wind industry, every news article and media report must generate a positive narrative about the industry.

In 2016, when Block Island Wind was being constructed, General Electric, the supplier of the wind turbines, as well as representatives of Deepwater Wind, the project’s developer, expected the five 6-MW wind turbines to produce 125,000 MWh of power annually. The GE press release of March 18, 2016, stated the following.

Led by Deepwater Wind, the Block Island wind farm will use five 6-MW GE “Haliade” turbines to generate 30 MW of power, enough to produce around 125,000 MWh of electricity, thus meeting approximately 90% of Block Island’s electricity demand.

Senior Editor Meghan Gambino’s article of August 25, 2016, in Smithsonian Magazine, contained the following paragraph in an extended story about the nation’s first offshore wind farm.

The 30-megawatt Block Island Wind Farm is miniscule compared to Europe’s offshore farms. But it gets the job done: Each turbine can generate enough electricity for up to 5,000 homes. “But because of what they call the ‘capacity factor,’ which basically allows for the fact that the wind doesn’t blow all of the time, we think of these five machines as being able to supply electricity for 17,000 homes,” said Tim Brown, public affairs leader for GE Renewable Energy. The 125,000 megawatt-hours of electricity produced each year should meet 90 percent of Block Island’s power needs.

An August 23, 2016, article by CleanTechnica discussing the construction of Block Island Wind and the role of larger turbines offshore compared to onshore wind turbines, contained the following statement. “But while the average capacity factor for onshore wind in the United States was only 33% in 2014, Deepwater Wind forecasts that the Block Island Wind Farm will have a capacity factor of 47%.” A GE public relations executive cited the 47% capacity figure as equal to an output of 125,000 MWh annually.

By rewriting history and reducing the threshold for what is considered a successful offshore wind farm, ProJo’s climate reporter scored Block Island Wind as perfect except for maintenance-impacted 2021. That year was excused because all wind farms require maintenance. However, a new wind farm with only a four-year operating life would not be expected to require as extensive an amount of maintenance as this wind farm. One reason why the maintenance was extended was because cracks were found in the turbines that required extensive examination to confirm they were not a risk to the functioning of the turbines. These cracks were first discovered in similar model turbines from GE installed in Europe.

While the wind farm then outperformed the 100,000 MWh threshold in 2022, it is in danger of underperforming this year. Only in one year (2020) did Block Island Wind’s output surpass 120,000 MW but by only 229 MW. Still, 2020’s record production fell 4% below what GE and Deepwater Wind told the public would be normal annual output.

In the ProJo article, the climate reporter wrote: “Ørsted considers the Block Island project a success.” He followed up with the following:

“The Block Island Wind Farm not only made history as America’s first offshore wind farm, but it also continues to perform well and meet its contractual obligations to supply clean energy to Block Island and the mainland grid,” the company said in a statement. “The Block Island Wind Farm is setting the standard for the American offshore wind industry.”

What the climate reporter failed to note was that Ørsted was not the wind farm’s developer, it purchased it from Deepwater Wind’s equity holder, hedge fund investor DE Shaw, for $510 million in 2018. Block Island Wind was estimated to have cost $300 million but there may have been an undisclosed equity component in addition. As part of the purchase, Ørsted received all the additional leases Deepwater Wind had acquired, so it is impossible to assess the exact profit DE Shaw earned from Block Island Wind, but we assume the hedge fund earned its target rate of return on the investment. If DE Shaw was able to pay down a substantial amount of the debt the wind farm was carrying, the return on the hedge fund’s equity investment would be very attractive.

We guess that a new owner of Block Island Wind provides the opportunity for it to set output expectations. The ProJo climate reporter pointed to Deepwater Wind’s rate case filing with the Rhode Island Public Utility Commission. In that filing, Deepwater Wind used lower output figures in its hypothetical explanation of how its contract pricing would work. That would suggest that Deepwater Wind had no confidence in the output figure GE cited and was frequently repeated by the developer’s officials.

The following chart shows the annual output of Block Island Wind for 2017-2023 year-to-date. We show the utilization rate (capacity factor) history and the expected rate that supported the 125,000 MWh cited by GE and Deepwater Wind.

This year is shaping up to be a disaster in supplying Block Island and Rhode Island with offshore wind power.

What GE and Deepwater Wind told the public at the time it was building the wind farm was that it would meet the electricity needs of Block Island. While that was probably true during the winter months, it was probably not true during some summer months when the island’s population expands dramatically and tourism demand boosts power consumption. That was especially true when the wind farm was undergoing maintenance, which suggests they would have been relying on the power cable connecting the island with the mainland.

In 2021, it was reported that the Block Island electricity company restarted its four diesel generators to provide power while the wind turbines were undergoing maintenance. The backup generators are maintained for when the mainland power cable has problems. It needed to be reburied at the Block Island landing point because when the cable was initially installed it was not buried to the depth recommended by the engineers due to a rockier ocean bottom than assumed. Avoiding the expense of the deeper burial initially ultimately cost National Grid much more when the cable had to be reburied.

Now, the entire utility system and cable is the responsibility of its new owner, Rhode Island Electric, a subsidiary of Pennsylvania-based PPL Corporation. They have a different way than National Grid of purchasing natural gas supplies that should lead to a less expensive supply. The more interesting development is Rhode Island Electric’s role in rejecting the latest offshore wind proposal from Ørsted and partner Eversource. We have yet to see the analysis of the rejection, but it will be interesting reading given the current turmoil in the offshore wind market. It will also be interesting given the underperformance of Block Island Wind.

September’s Stock Market Was Terrible But Not Energy

According to Dow Jones Market Data, September is historically the worst month for stocks. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index has averaged a 1.1% decline in September since 1928. The ninth month of the year is when summer optimism fades and investors shift their focus to trends that will impact the next year’s economy and stock market. This September was no different. For the month, the S&P 500 index fell 4.77%, with only one of the 11 industry sectors posting positive results – Energy. That performance was not surprising given what happened to crude oil prices which are the driving force behind the sector’s earnings and stock prices.

Saudi Arabia and Russia have led OPEC+ in seizing control of oil pricing by agreeing to increase their production and export cuts, further tightening the global supply/demand balance. For much of this year, the organization’s cuts were designed to offset the weakness in Chinese oil demand as its economy struggled to recover after reopening from its pandemic lockdown. Rather than soar, as seemed initially to be China’s economic trajectory, the country’s demographic and financial woes held down growth and oil consumption. This was against a backdrop of an anticipated global economic recession that would cut oil use.

As the economy performed better than expected and inflation declined, offering the possibility of a less stringent monetary policy to slow economic growth, oil demand began picking up. But Saudi Arabia and Russia decided that they wanted higher oil prices, so they added to their production cuts and then vowed to hold them through the end of 2023. Global oil inventories began shrinking, especially for diesel fuel which is the workhorse of economies. Summer gasoline demand in the U.S. remained healthy and jet fuel demand globally was strong as tourism surged. Global oil markets continued to tighten. Suddenly commodity traders recognized that an extended cycle for crude oil was unfolding. Looking forward to ever-tightening supply/demand balances as U.S. oil drilling activity continued to slump, traders began buying oil futures in anticipation of higher prices. Their buying helped to drive oil prices higher, surprising investors who were still wrestling with the uncertainty about the vigor of the economy.

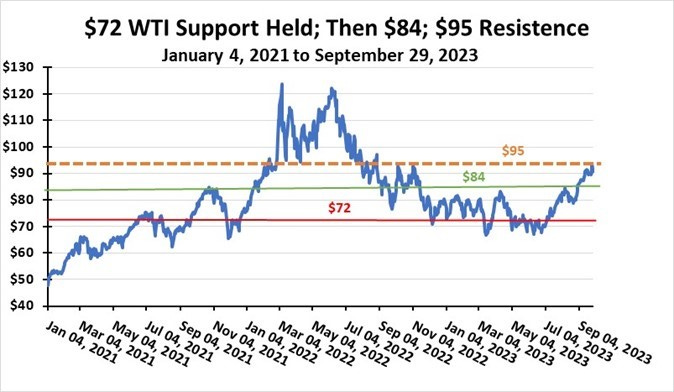

From $70 a barrel at the start of July, WTI oil futures prices rose to $82 by the end of the month. August saw the oil market trade sideways and oil prices only rise a dollar a barrel. September saw the market take off – going from $83 to $91 over the month, but prices settled lower in its final days after touching $94 a barrel. The last half of September was marked by extended discussions of how high oil prices might go. 100 a barrel? $150? Maybe even higher if there were a supply accident. What was becoming certain in the minds of many investors was that higher for longer might apply not only to interest rates but also oil prices.

The third quarter proved significant for oil prices as they were supported at $72, and broke resistance at $84 before reaching the next resistance at $94. Going higher?

Our monthly S&P 500 sector performance chart shows that September was the third consecutive month for Energy to be the top-performing sector. That has not happened going back as far as 2020. Not only was Energy the best-performing sector for the month, but it was also at the top of the list for the third quarter, posting a gain of 12.22%.

Equally impressive was Energy climbing into fourth place for year-to-date performance. At the end of June, Energy was in 10th place with a year-to-date performance of -5.52%. At the end of September, not only had Energy climbed six places in the ranking, but it had turned that negative mid-year performance into a positive 6.03% return. Can this performance continue? Watch what happens to oil prices.

September marked the third consecutive month of Energy topping the S&P 500 sector rankings.

This is not stock market advice, but if oil prices remain at this elevated level, the industry’s participants will have healthy cash flows to reinvest in the business as well as pay down debt, and return money to investors. Importantly, the Energy sector still represents less than 5% of the S&P 500 index. That means that energy stocks have relatively small capitalizations and are thus subject to outsized price moves when trading volume in their shares increases either up or down. Therefore, what happens to crude oil prices in the fourth quarter will determine how energy stocks perform as well as the Energy sector.