Energy Musings - November 21, 2024

A new analysis using current population and GDP growth projections shows the over-estimation of the global temperature rises by the IPCC's climate models. It is time to modernize them.

Updated Model Inputs Undercut Climate Alarmism

Climate scientist Roger Pielke Jr. writes about his recent analysis of climate model temperature predictions by incorporating updated global population and GDP projections. He did this because the climate predictions from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) models depend on decades-old data inputs and are responsible for the catastrophic outlook.

People may be surprised that Pielke’s study finds we are on track to meet the UN’s 2ºC temperature rise by 2100 compared to pre-industrial days because all they have heard is the impending catastrophe narrative. The analysis should cause people to stop and ask about the basis for climate alarmism. Is it based on science, and what is that science? Or is it manipulated to empower the world’s elites who will dictate how the eight billion people live their lives?

The timing of Pielke’s study, reported in his Substack newsletter, coincided with the release of the UN Environment Program’s (UNEP) latest “emissions gap” report as we headed toward the opening of the UN COP 29 climate conference. The conference is being held in the iconic oil city of Baku, Azerbaijan with its long history of helping develop the world’s oil industry.

The narrative ahead of the conference was how hot the climate has been in 2024. This led to a demand that national climate pledges increase to prevent global temperatures from creating a climate disaster.

The UNEP report warned of a “massive gap between rhetoric and reality.” It said the chance of limiting global warming to 1.5ºC is “virtually zero” based on current trends. All the mainstream media and climate activists covered the report. In response to UNEP’s comment that greenhouse gas emissions were the highest ever recorded, Carbon Brief noted that there needed to be a “quantum leap” in country climate pledges.

The Financial Times wrote that the world is on course for a “catastrophic” temperature rise of more than 3ºC above pre-industrial levels. Moreover, it noted the chance to limit the warming to 1.5ºC “will be gone within a few years” without quick action.

The Guardian reported that current national emissions-cutting commitments for 2030 are not being met. Even if they were, they would only limit the temperature rise to a “still disastrous 2.6ºC to 2.8ºC.” The 3.1ºC figure “isn’t strictly new” chimed in the BBC because it is “in line” with the projections from the latest IPCC assessment. Their estimate refers to its likelihood being greater than 66%.

Reuters quoted UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres: "We're teetering on a planetary tightrope. Either leaders bridge the emissions gap, or we plunge headlong into climate disaster." Is that worse than his prediction that “the era of global boiling has arrived”?

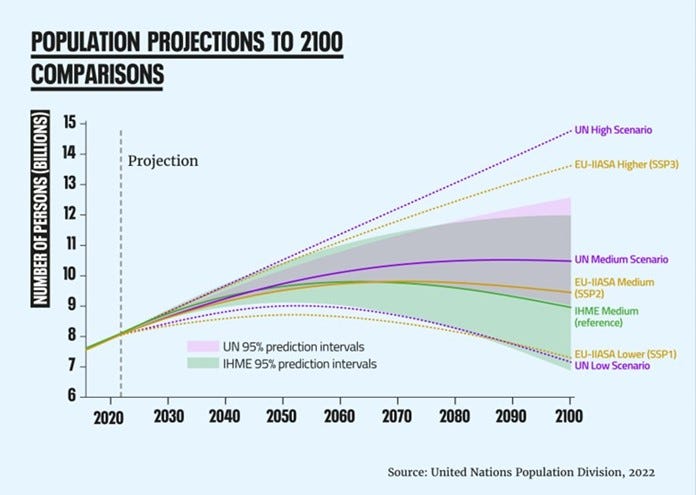

Pielke’s study was triggered by a column by opinion writer John Burn-Murdoch in the Financial Times titled “Peak population may be coming sooner than we think.” The article focused on the record of global population projections consistently overstating growth. The culprit is the UN World Population Division’s annual projections. While the UN is the gold standard for population projections because of their historical accuracy, two other respected institutions also provide estimates. They are the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) in Seattle and Vienna’s International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA).

As Burns-Murdoch points out, the forecasting models use different inputs, although the key ones are demographic and economic. However, some forecasters also incorporate assumptions about social change in estimating how the key metrics might change in the future.

The most recent UN World Population central estimate has the global population peaking at 10.3 billion people in 2084, 60 years from now. However, IIASA sees the peak arriving in 2080 with 10.1 billion people, while IHME has population reaching 9.7 billion in 2064. The problem with all these estimates is that forecasters have been overestimating the birth rates of countries when compiling the global total. For example, Burns-Murdoch points out that five years ago the UN forecasters had South Korea’s birth rate for 2023 at 350,000 when it was 230,000, a whopping one-third less.

The FT article contained a series of charts showing various countries’ birth rate histories and projections used by the UN and other forecasters. Here is one showing the record for Latin American countries. The collapses are incredible, just as are the projected decline rates. Many countries have current birth rates below the lows projected for 2050. Mexico was cited in a separate graph showing how its birth rate has now fallen below that of the United States.

The surprising fertility decline.

An early 2023 report by populationmatters.org looked at the forecasting estimates. It acknowledged that the relative accuracy of past projections by the UN Population Division is why it is recognized as the gold standard. However, the study’s author wondered whether the other two organizations had stronger models and might be more accurate going forward. The following chart shows all the forecasts from 2022 to 2100.

What if we are on the low fertility path?

The high scenarios never peak, but based on the latest birth rate trends appear unrealistic. Two population issues in driving climate projections are key. When might the world’s population growth peak? What if we are on a path of low population growth scenarios?

Pielke focused on the “current policy” projections for global temperature increases by 2100. Carbon Brief had just issued a report with a chart of three different “current policy” projections in the center. It shows that by 2100, global temperatures above pre-industrial levels are projected to be:

• 2.9ºC by UNEP

• 2.7ºC by CAT (Climate Action Tracker)

• 2.4ºC by IEA (International Energy Agency)

The current outlook for global temperature increases.

Global average surface warming projections in 2100 relative to pre-industrial levels from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (dark blue bars), UNEP report (mid blue), Climate Action Tracker (light blue), and IEA 2004 World Energy Outlook (grey). Bars show the central (50th percentile) estimate, while uncertainty ranges are shown by the upper and lower lines. Chart by Carbon Brief.

Note the central point of the current policies forecasts is 2.7ºC. That is the same temperature forecast as the IPCC’s SSP2-4.5 mid-point scenario. This provides the starting point for Pielke’s analysis.

Burns-Murdoch cited Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, a demographer and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. His calculations, based on the wide birthrate misses for emerging economies and the smaller overestimates for wealthy Western nations, have the world on the UN’s “low fertility” trend. Following this path means the world population peaks in 2054 at around 9 billion people, 30 years earlier than the UN’s central estimate.

Importantly, the Fernández-Villaverde estimate is about 20 years earlier and 500 million fewer people than in the IPCC’s SSP2 scenario. Assuming the population is related to carbon dioxide emissions over the 21st century, then fewer people means fewer emissions and a lower global temperature.

The lower population projection is similar to the forecast used in the IPCC scenario SSP1. Pielke notes that the Kaya Identity formula says that, all else being equal, fewer people means less carbon dioxide emissions. He then writes, “If we simply assume that cumulative emissions over the 21st century are proportional to population, then replacing SSP2 population with SSP1 population under the SSP2 scenario results in 11.6% less carbon dioxide emissions over the century.”

More people and GDP equals more emissions.

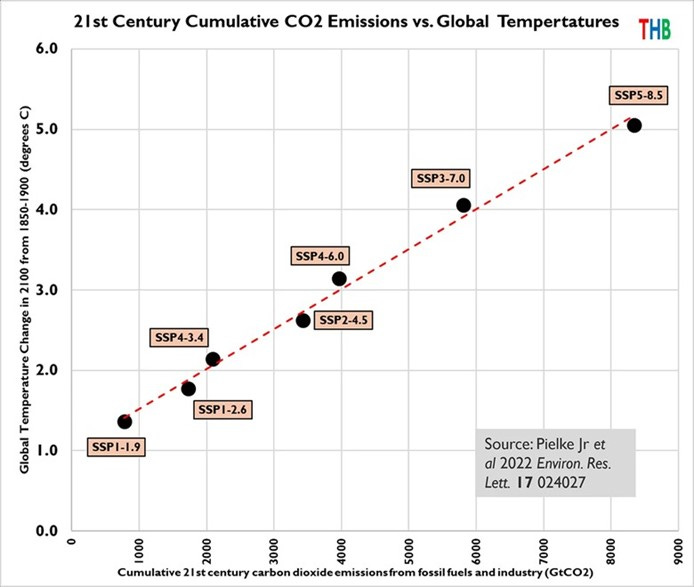

In projecting future global temperatures, Pielke utilized a linear relationship between cumulative carbon dioxide emissions of the 21st Century and 2100 global temperatures for the seven primary IPCC climate scenarios. This chart allows Pielke to estimate what happens to the 2100 global temperature when using the cumulative emissions under SSP1 population assumptions for SSP2-4.5 projections keeping all else equal.

Pielke also analyzed the consequences of global temperatures by using alternative assumptions about GDP growth under current policies. He used the work of Matthew Burgess, an economics professor at the University of Wyoming, and a past collaborator on climate research studies. Burgess recently produced a study showing future GDP growth will be lower than assumed in the SSP2 scenario.

Burgess and his co-authors of a paper on economic growth published in 2023 in the journal Communications Earth & Environment wrote:

“[S]low-growth, slow-convergence economic scenarios deserve greater attention in research and policy, and that the range of economic scenarios treated as plausible in research may need to be revised in this direction. SSP4 is currently seen as a worst-case scenario for global income convergence and a relatively slow-growth scenario. In contrast, SSP4 is modal compared to our projections, which would have over-projected economic growth and income convergence historically. This suggests that SSP4 might actually be a more realistic best-case scenario for growth and convergence.”

Pielke used two projections from Burgess to bracket SSP4 GDP projections to 2100. One projected slightly lower growth (DEM) than SSP4 while the other projected slightly greater growth (ADEM).

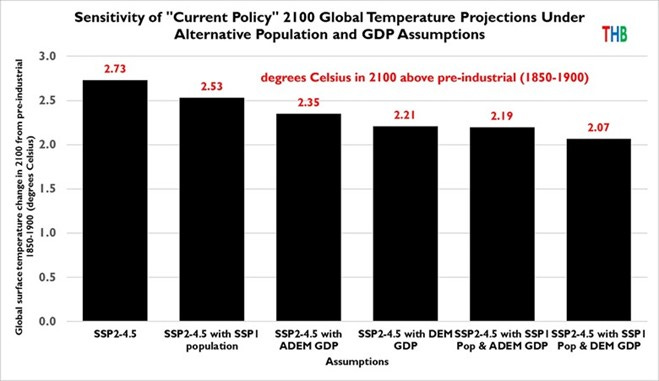

With the population and GDP projections, Pielke could project 2100 global temperature changes under various combinations of population and GDP growth compared to SSP2-4.5. The analysis produced the following chart.

How temperatures change with fewer people and less GDP.

The leftmost column shows the 2100 temperature change for SSP2-4.5 to be 2.73ºC. The next three columns show the results using the lower population projection, then the slightly higher GDP growth, and finally the slightly lower GDP growth forecast. The two rightmost columns combine the slower population growth with each of the two GDP growth projections. Each of these slower growth projections results in less global warming, with the largest reduction (0.63ºC) occurring when slower population growth is combined with a slower increase in GDP.

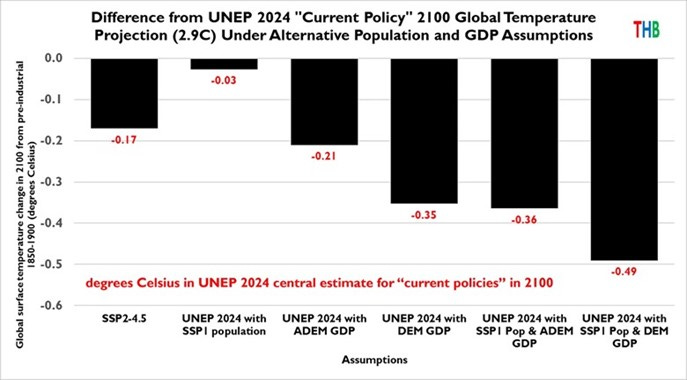

Pielke then compared the impact of the slower growth projections on the latest UNEP “current policy” forecast. That projection has a central estimate of a 2.9ºC rise by 2100. The range of changes is from essentially zero to upwards of -0.49ºC. The latter estimate would bring the UNEP central estimate down to 2.4ºC. If the reduction were applied to the IEA’s “current policy” projection of an increase of 2.4ºC, we would be around 2ºC, or in line with the Paris Agreement target.

Adjusting “current policies” means no climate catastrophe.

Pielke’s analysis showed that the models whose outputs guide climate policy are out of date. He pointed to scenario SSP3, with its global population projection of 13 billion people and rising, which has been used in 1,500 papers in 2024 so far.

The revised population and GDP projections are considerably different from the assumptions driving many IPCC disaster scenarios such as RCP8.5, referred to as “business as usual,” which requires a dramatic coal use increase. Pielke argues that the IPCC must update its forecasting scenarios to be more consistent with real-world observations.

He acknowledges that peak population and slower GDP growth bring their own set of societal and policy challenges. However, it is incumbent on the IPCC to recognize that its “current policy” projections are based on conservative assumptions, ignoring the reality that there will be new climate and energy policies. Additionally, the declines in fertility rates caught demographers by surprise. It is silly to believe there will not be other surprises in the future.

Failing to update climate models to account for real-world changes and trends leads to conclusions that increase skepticism of their policy prescriptions. However, Pielke should understand that without these out-of-date climate models, the climate disaster narrative would be impossible to sustain. This may be why few people other than subscribers to Pielke’s newsletter have read this analysis and his sober thinking and approach to such an important and divisive economic and societal issue.