Energy Musings - May 25, 2024

Lawfare is popular for attacking the oil and gas industry. The FTC used it against ExxonMobil. Now TotalEnergies is being sued in Europe for climate murders. Watchfor it spread to Washington, D.C.

Big Oil Knows Lawfare Well

The attack on former Pioneer Natural Resources CEO Scott Sheffield is just one more among many lawfare episodes involving the international oil industry. Not all of them are driven by the Biden administration and its agencies, but they and their fellow Democrat politicians are active participants.

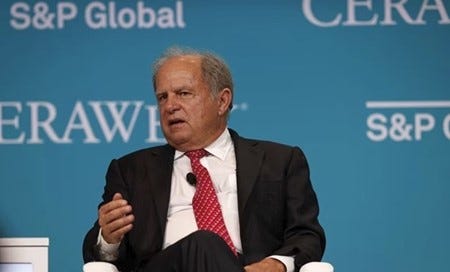

Pioneer Natural Resources CEO Scott Sheffield speaking about oil and gas market conditions at CERAWEEK.

The Sheffield episode is one example. He was banned from accepting a seat on the ExxonMobil board of directors following the Pioneer merger without the opportunity to defend himself. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which is charged with evaluating and approving industry mergers based on compliance with federal antitrust laws, issued a complaint and an order. By accepting the order and dealing with the complaint, ExxonMobil secured FTC approval to complete the Pioneer merger.

The 3-2 vote by commissioners stipulated that ExxonMobil agreed to not appoint or nominate Sheffield to be a member of the company’s board of directors for the deal to be approved. The three commissioners who voted in favor of this procedure were the Democrat members. Their approval vote drew a sharp dissent from the two Republican commissioners who questioned the justification for the majority’s decision.

Republican FTC Commissioners Melissa Holyoak and Andrew Ferguson wrote in their dissent:

“…Exxon’s consent to the entry of this order and its decision to exclude Mr. Sheffield from its board does not answer the ultimate question the Commission must answer before issuing a complaint: Whether the Commission has reason to believe this transaction itself violates Section 7. The Commission’s Complaint does not provide us with reason to believe that it does. The Complaint fails to articulate how the “effect of [the] transaction may be substantially to lessen competition.” We fear instead that the Commission is leveraging its merger enforcement authority to extract a consent from Exxon rather than addressing the conduct of one misbehaving executive.”

These commissioners discussed the “three factors in assessing the risk of increased coordination,” which is the test of Section 7 of the Clayton Act. They explained the factors used before the FTC revised them last year and the new ones. The commissioners declared that the complaint was unclear on which of the three factors were present in the merger evaluation. The two dissenters said the complaint focused on “actual or attempted attempts to coordinate.” They did not agree with the majority’s view that “Mr. Sheffield’s history of attempting to coordinate with other oil industry participants suggests that the market here is susceptible to anticompetitive coordination.”

The dissenting commissioners wrote: “The Complaint alleges only that a combined OPEC and OPEC+ ‘account for over 50% of global crude oil production.’ Importantly, it does not allege the merging parties’ market shares at all. As such, it fails to allege that either Exxon or Pioneer represents part of any ‘substantial share’ of the market, and for good reason: the post-merger firm’s share in the alleged market will not be substantial. The concentration in this market, and thus, the likelihood of successful coordination post-merger, are virtually unchanged by the proposed acquisition.”

Neither ExxonMobil nor Pioneer have meaningful shares of the world oil market. The combined oil equivalent production this year will be 1.6 million barrels a day. Generously, it represents 1.6% of world oil production. It is hard to see the merged ExxonMobil/Pioneer representing a “substantial share” of the global oil market.

The dissenting commissioners wrote: “…we are especially concerned with the Complaint’s focus on Sheffield’s past conduct at Pioneer as an indicator of Exxon’s future actions, without any discussion of whether Exxon has incentives to engage in the same behavior. Focusing on individuals’ conduct divorced from a firm’s incentives could have troubling ramifications for future enforcement actions. That is an ominous warning.

The FTC used an assortment of WhatsApp private communications between Sheffield and representatives of OPEC about the efforts of U.S. shale oil producers to control their output as evidence of collusion. There were also public statements Sheffield made about the need for financial discipline by shale producers and how they should lobby the Texas Railroad Commission (TRC) to get involved in regulating output as it did in the 1930s. The workings and success of the TRC during the Depression years were the model for OPEC’s formation in the 1960s. However, it was only when U.S. oil production ceased growing in the early 1970s that the center of global oil industry pricing power shifted to the Middle East and OPEC members.

Many of Sheffield’s statements about producer capital discipline reflected the widely held sentiment of investors and Wall Street analysts. The 2010s saw rapid oil and natural gas production growth as shale oil and gas producers capitalized on and improved directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing technology. The industry engaged in a race to grow output at any cost, which destroyed their balance sheets, finances, and shareholder returns. Financial discipline became the Wall Street mantra for the industry with investors promising to snub those producers who failed to exercise this discipline and return excess capital to shareholders. This message was not collusion. Moreover, Pioneer’s production more than doubled between 2019 and 2023, as U.S. total output grew enabling it to become the world’s largest producer. This record output becomes a problem for the FTC in making a case against Sheffield.

The key point the dissent FTC commissioners made about the majority’s opinion was stated thusly:

“The alleged conduct by Mr. Sheffield warrants scrutiny, but that does not mean we have reason to believe the transaction violates Section 7. The Commission should not leverage its merger enforcement authority—or any authority—the way it does today.”

The final point the dissenting commissioners wrote is telling. It highlights that attacking Pioneer’s Sheffield for communicating his views of oil market dynamics during the downturn in oil prices is dangerous. The FTC majority commissioners want to use antitrust law to promote their anti-oil views in keeping with those of the Biden administration. This is dangerous lawfare.

Jumping across the pond, we see a new chapter in oil industry lawfare. TotalEnergies directors, led by the company’s chief executive officer, are being criminally charged with responsibility for the widespread fallout from extreme weather events. Non-profit environmental groups filed the suit. The charges also include involuntary manslaughter for the deaths associated with these extreme weather events.

Legal academics say this is a novel case that relies on a body of science that attributes such events to climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions. While this may be the first case, the idea of charging oil companies with murder has been floating around environmental legal circles for a while.

European energy writer Irena Slav proposed conducting a science experiment to test the climate change/extreme weather events theory. Let’s switch off all fossil fuel use for a month. Her idea is to employ the scientific method – propose a hypothesis and then test it with a scientific experiment. She initially proposed a shutdown of one week but realized it was too short for the impacts to be measured. Ponder how Europe and North America would look after 30 days without oil, natural gas, or coal power. Without oil and gas, we are looking at the pre-1850 era. Absent coal, we are back to the 1700s. How many people want to live like that, especially environmentalists?

Back in the U.S., the most recent lawfare episode comes from the calls by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (RI-D) and Representative Jamie Raskin (MD-D) for the Department of Justice to investigate the oil industry over its questioning climate change claims and their role in creating global warming. The claim is based on the recent report of the Senate Committee on the Budget headed by Whitehouse.

The three-year investigation is the basis of the report. It found that the oil industry deceived the public about climate change since at least the 1960s. The report claims, based on documents it obtained from the oil companies, that the oil industry shifted its strategy of fighting climate change from outright denial to disinformation and doublespeak over the years.

This is the latest chapter in the “Exxon knew” climate change campaign. The campaign goes through periodic revivals. Recently, several of the children’s climate change lawsuits based on the claim have run into problems and have been shut down by the courts. The idea there is a direct linkage between the burning of fossil fuels, climate change, and extreme weather events is becoming harder to prove. Even the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has trouble supporting attributions that climate change has increased various forms of extreme weather events. Assigning every social ill to the fossil fuels industry without giving it credit for the social benefits is a serious distortion of reality.

As we head toward the November election, expect lawfare against the oil industry will ramp up. We expect to be commenting on this issue in its various forms for the next six months.