Energy Musings - May 23, 2025

A proposed plan to attract skilled workers from the middle of the U.S. for temporary work at coastal shipyards may solve its labor problem. It follows the offshore oil industry's work plan.

One Energy Sector Helps Another

The Trump administration started an effort to revitalize the domestic shipping and shipbuilding industries on April 9th with an Executive Order, “Restoring America’s Maritime Dominance.” The EO instructs multiple government agencies to develop a Maritime Action Plan to marshal existing and available resources, coordinate with our allies, and create various financial incentives for the domestic shipbuilding and shipping industries.

Two recent articles in Foreign Affairs magazine highlight the challenges the U.S. maritime industry faces due to long-ago government policy decisions. They focus on how the U.S. fell far behind China and had fewer shipyards, a smaller navy, and commercial fleets. One article addresses the U.S.'s economic and military challenges in “Underestimating China,” which made shipbuilding a tenet of its industrial strategy. Two former members of Biden’s National Security Council staff wrote the paper. The Director of the Defense Innovation Unit of the Defense Department during the first Trump administration authored the second paper. “The Empty Arsenal of Democracy” lays out steps the government needs to undertake to build a new defense industrial base, which includes shipbuilding.

Each paper points out the shortcomings of the other administration’s policies, but both suffered from a bureaucratic mindset that failed to see the dangers in continuing old policies. Surprisingly, these former government officials arrive at a similar conclusion‒China is a more formidable opponent than policymakers think, and our hollowed-out defense manufacturing capacity exposes the U.S. to losing a war with China. War games predict the losing outcomes. Such an outcome is not acceptable and demands action.

Overcoming our vulnerabilities is a must. Trump’s maritime plan is similar in thrust to the bipartisan SHIPS for America Act, which was introduced to Congress last December and recently reintroduced in the new Congress in April with minor modifications. A key one is splitting the legislation into two bills that allow the operational steps and the tax provisions to move forward in tandem rather than sequentially, as would have happened with the earlier bill. Faster resolution of the challenges is imperative.

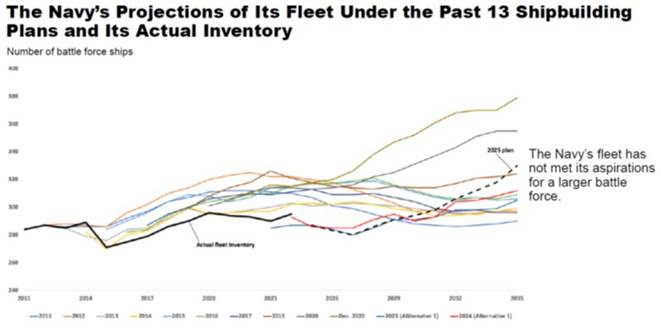

In 2024, a Congressional Budget Office presentation about the shortcomings of the Navy’s 2025 shipbuilding plan contained the following slide as its conclusion. Notice how the current Navy fleet is below the prior projected fleet sizes and only grows in the latter years of the forecast. That reflects the long time necessary to build military vessels.

The U.S. Navy continues to fall short of projected fleet growth forecasts.

The Arsenal paper identifies the root of Washington’s military shortcomings. It dates from a meeting at the end of the Cold War in the 1980s, which is known as the Last Supper. The Defense Department encouraged defense manufacturers to merge, figuring that the anticipated decline in defense spending meant insufficient purchasing power to support the industry as it was currently structured. The companies listened and responded by gobbling up each other. The paper outlined the resulting problems that impact the sector today.

“The toll has been profound. In addition to raising prices, this consolidation has allowed firms to shed manufacturing capacity with little consequence—including by switching to narrow, just-in-time supply chains that are highly vulnerable to disruption. Today, just one company supplies the turbofan engines used in most U.S. cruise missiles. Consolidation and an increasing focus on short-term shareholder value has also led to more financial engineering designed to increase share values, such as repeated rounds of stock buybacks. The result is less investment in the adoption of new technologies, output, or long-term research and development.”

To appreciate the national security implications of the deterioration of our shipbuilding capacity, the Arsenal paper states the following.

“Washington is also in need of new ships and planes—the average navy vessel is 19 years old, and the average air force plane is 32 years old. Some ships and planes are 50 years old. On average, major defense systems such as these take more than eight years to make. Meanwhile, 70 percent of the ships in China’s navy have been launched since 2010. China’s annual shipbuilding capacity is also 26 million tons, or a staggering 370 times the United States’ shipbuilding capacity of 70,000 tons. The United States does not even have enough industrywide capacity to make a single Ford-class aircraft carrier per year. (These carriers weigh 100,000 tons.)”

The Biden officials noted “China’s navy, already the largest in the world, will add a staggering 65 vessels in just five years, reaching a total size 50 percent larger than the U.S. Navy—roughly 435 vessels to 300. It has rapidly increased its ships’ firepower, surging from one-tenth of the United States’ vertical launch system cells a decade ago to likely exceeding U.S. capacity by 2027.”

These figures from officials in the two most recent governments are shocking. The comparisons in aircraft, missiles, and drones are even worse. Regarding our ammunition supplies, we could be out of business in a matter of weeks if we were to become involved in a military confrontation with China. Part of that shortfall lies with our supplying Ukraine with missiles, but not replenishing our inventory quickly. For example, the Stinger missiles we gave Kyiv were designed in the 1970s. They were last ordered by the military 20 years ago. The defense contractor Raytheon had to bring back retired engineers to make new ones. It had to re-create obsolete components. These bottlenecks limited Raytheon to making just 60 Stingers per month in 2024.

A General Accounting Office study of the U.S. shipbuilding industry indicated the dependence on old equipment. Many of the cranes and other equipment in shipyards are decades old. It has forced owners to fabricate replacement parts because none are available commercially. Our shipyards need massive investment to upgrade their capacities and capabilities. These investments will contribute to the shipyards becoming more productive, which is key to speeding up new vessel delivery times.

Labor for shipyards and ship repairs is another problem. Skilled craftsmen are in short supply. One pilot program developed by Bartlett Maritime Corporation, in partnership with the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, will bring skilled workers from the middle of the country to work in coastal shipyards without having to relocate.

The Rotational Workforce program aims to increase workforce capacity beyond the geographical boundaries of shipyard locations. The program would enable shipyards to hire workers from the “heartland of our nation and find people who have the skills, training, and experience to do these jobs – but who don’t want to leave their homes and permanently relocate near a shipyard or other key suppliers,” as Edward Bartlett founder and CEO of Bartlett Maritime told the Boilermakers at their recent annual conference.

He pointed out that the average age of submarines is 40 years old. We have 66 in the fleet, but only 48 are operational. Bartlett noted that the Navy orders two Virginia-class submarines yearly, but only 1.2 are delivered annually. That is because of the shortage of people and parts. He said there used to be 17,000 companies supplying parts, but we are down to only 5,000.

The rotational workforce model is based on the oil and gas industry’s successful offshore labor scheme. Workers on drilling rigs and platforms live and work on the facility for several weeks or a month. They then return home for a similar period. When the workers are offshore, they work 12-hour shifts daily. They are provided with accommodations, meals, recreational facilities, and healthcare. This is not a lifestyle for everyone, but it is an attractive opportunity to earn high wages while still being able to live at home half the year. Many offshore workers can even sustain sideline businesses during their at-home times.

There are other examples of this employment scheme in the oilfield. Crews that operate fracking equipment, which is a 24-hour process when jobs are underway, often work 14 days on and 14 days off, while living in nearby labor camps. Oilfield workers come from across the nation and the world to work on drilling rigs, offshore platforms and vessels, fracking crews, and other intense industry jobs requiring 24-hour activity. The pay can be good, with few opportunities to spend their wages when deployed.

Bartlett’s idea is that many skilled workers in the middle of the U.S. have suffered from the abandonment of domestic manufacturing over recent years. They will now have an opportunity for great jobs utilizing their skills but not being forced to relocate, as many manufacturing workers did in the 1970s in response to the recessions caused by the 1973 Oil Crisis.

While not a perfect solution for the shortage of skilled craftsmen needed by shipyards, it offers an opportunity to overcome a key impediment to ramping up activity. The shipbuilding industry will require significant capital investment to upgrade existing yards and to create new ones. The Biden officials recognize that the United States alone cannot overcome its problems and compete with China. They suggest a coordinated effort with our allies that would enable shipbuilders in Japan, Korea, Canada, and Europe to begin building ships that would be granted U.S.-flag status, in return for a program for them to start constructing new shipyards in the U.S.

It will take creative thinking to repair the deterioration in our maritime industry. It will take equally creative efforts to address the other defense industry shortcomings we must overcome for national security. We were pleased to see how one energy industry‒oil and gas‒ may help another‒shipbuilding‒ overcome its long-standing labor shortage challenge.

One point to remember is that many of those potential inland workers are acculturated to union shop conditions. In the US oil and gas industry, offshore field workers and even the supporting shipyards, (other than those working for the military) are not union. Admittedly, other countries do have union shops for their oil and gas operations. The US dominated offshore development without that attribute.

Secondly, the Jones Act, and earlier cabotage laws, have been successful in gutting the maritime world of international competitiveness. Step one should be to allow foreign built ships to be US flagged for strategic, point to point, transportation. We can use the Military Sealift Command as a template. For decades their fleet has been sourced from foreign shipyards, but flagged and crewed under Jones Act rules. Borrowing from the Asian model, we could gradually supply more and bigger modules to those foreign assembly yards, e.g. power trains, thruster3s, cranes, DP software, drilling packages etc.