Energy Musings - May 14, 2024

The struggle of BP and Shell to close the stock price valuation gap with American IOCs continues. If there were a simple solution, the CEOs would have acted. The European media seeks answers.

Understanding The Great Oil Industry Divide

The Financial Times is focused on the thoughts of European-based international oil company CEOs about the valuation of their shares. The latest article focused on the two UK-based companies – BP p.l.c. and Shell plc – and their CEOs’ efforts to boost shareholder returns. Having failed to deliver returns under prior CEOs, each company is going “back to basics to boost shareholder returns,” according to the FT.

The shifts are led by the new CEOs who understand that their company shares have underperformed the prices of their industry compatriots across the pond. The underperformance is demonstrated in the chart of stock performances of the two U.S. and three European IOCs presented below. The FT article was focused on the impact of BP embracing aggressive climate targets in 2020 and the subsequent underperformance.

European IOCs have trailed the stock performance of their American counterparts.

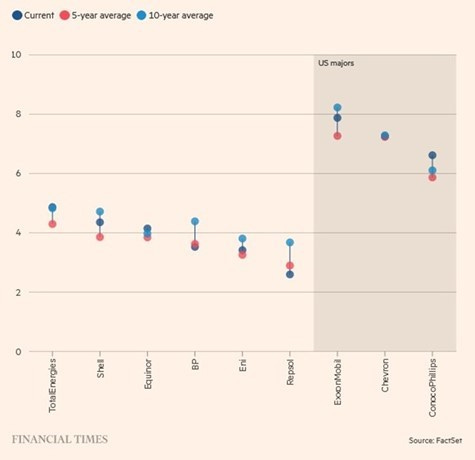

The BP/Shell article carried the chart below (one shown numerous times over the past year) showing the valuations of the international oil company shares based on the then-current, 5-year, and 19-year averages of stock prices to forward consensus cash flow estimates. The chart includes all the European-based and U.S.-based IOCs. It shows how much the European IOCs trailed the stock price performance of ExxonMobil and Chevron.

The least valuable American IOC trades at a 30% valuation premium to BP and Shell.

If we focus on BP and Shell and their 5-year trading averages, we find that they trade at two-thirds of the valuation of ConocoPhillips, the lowest-valued U.S. company. Compared to ExxonMobil and Chevron, the valuation spread is wider. The highest-valued European IOC – TotalEnergies – trades at a modestly lower discount to ConocoPhillips than BP and Shell.

How to close this Atlantic Ocean valuation gap? That depends on whether the problems dogging European IOC valuations can be identified. Is it because the Europeans opted to devote more of their investment to climate change policies at the expense of more oil and gas? How much of the gap is because European IOC shareholders are more interested in social issues and less in monetary returns? What about the management of BP and Shell in recent years?

An early 2023 Bloomberg analysis suggested the valuation problem reflects differences in the IOCs’ net zero investment focus. As the analysis stated:

“A bigger factor is sustainable-energy investments. All four have targeted 2050 for reaching carbon net zero. But BP and Shell are investing about $1 billion a year each in low-carbon energy, and say their oil-and-gas production has peaked. Exxon and Chevron spend less as a percentage on green projects, and expect fossil-fuel output to rise.”

Mystery solved. It is all about the difference in climate investments among the companies. However, Bloomberg noted that “environmental, social, and governance investors avoid BP and Shell because they remain big fossil-fuel producers.” Ah, the curse of the legacy business. However, based on the low returns of clean energy investments, without the greater profits of the legacy oil and gas businesses, BP and Shell’s clean energy investments would be impossible to fund.

This business focus divide was evident in the aggressive merger and acquisition moves of ExxonMobil and Chevron and their respective deals with Pioneer Natural Resources and Hess Corporation. For European IOCs to become more aggressive, they must pay all or a substantial amount of cash in transactions or dilute existing shareholders by trading lower-valued shares for the higher-valued acquisition target’s shares. If the target is also undervalued versus U.S. companies, then the dilution from a stock merger would be less punishing for shareholders. The purpose of such a deal only makes sense if it is a “cost-reduction” transaction with only a modest increase in the combined company’s oil and gas production.

The challenge for European IOCs in such a cost-reduction transaction is that trying to close the valuation gap is complicated by the cost savings and oil and gas profitability increases ExxonMobil and Chevron have engineered with their deals.

For example, the ExxonMobil merger with Pioneer Natural more than doubles its acreage in the prolific Permian Basin. Moreover, the acreage it is acquiring is largely contiguous, enabling ExxonMobil to drill fewer but longer lateral wells and boost output while reducing surface costs. This will also allow the electrification of development and production activities and speed up reaching the company’s net zero target. The result of the acquisition is that ExxonMobil’s combined petroleum production will grow faster, reaching 2 million barrels a day by 2027, with a reduced breakeven profit price of $35 a barrel. Roughly 40% of the company’s future oil production will be “short cycle” barrels enabling rapid output adjustment to match demand volatility. That flexibility further aids profitability.

Neither Shell nor BP have shale operations matching those of ExxonMobil. Shell, having exited its U.S. shale operations in a 2021 sale to ConocoPhillips, certainly doesn’t. And BP’s operations are much smaller. Given the consolidation of shale producers in recent years, the number of potential acquisition targets is small. Their higher stock market valuations create a meaningful financial hurdle for European IOCs.

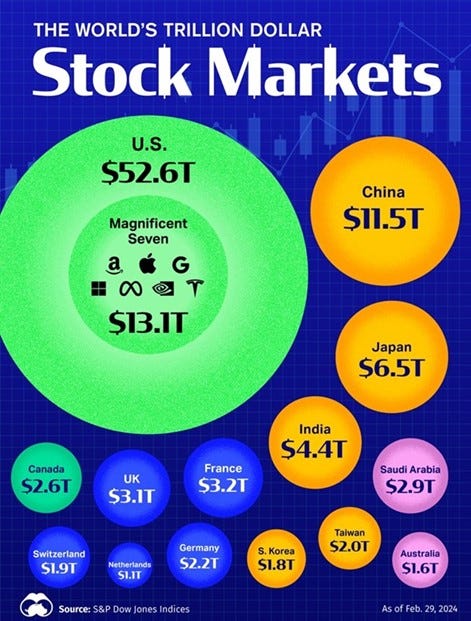

One of the bigger problems for European IOCs is something that afflicts all European stocks. They usually sell at lower valuations compared to U.S. stocks. That is probably because the U.S. stock market is more liquid. The chart below shows global stock markets by their market capitalizations. The U.S., at $52.6 trillion, is 17 times larger than the U.K. or French markets. If we combine all the European markets – U.K., France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland – the U.S. market is still 4.5 times larger.

The huge U.S. stock market provides greater liquidity that helps improve company stock valuations.

The smaller market capitalizations of these European exchanges make them less liquid – harder to trade in large volumes – and more susceptible to influence from local shareholders. A Citi analyst told the FT, “I don’t think European investors support the idea that oil-and-gas companies should grow anymore.”

If that view is correct, then the CEOs of BP and Shell adopting business strategies that slow their divestment of oil and gas assets and seek to grow production for the foreseeable future would make it very difficult for European investors to buy the shares. Without buying momentum, it is difficult to gain price-to-cashflow multiple expansion. Share price increases will depend solely on the growth of company cash flows per share.

A way to influence the per-share cash flows is for European IOCs to buy back more of their outstanding shares. It is a more efficient way to return capital to investors than through increased dividends. In February 2020, when BP’s then-CEO Bernard Looney introduced his new management team and its climate agenda, he warned BP pensioners and other shareholders that the green strategy and the sale of oil and gas assets would limit the growth in future dividends. It was probably a difficult pill for these former employees to swallow, as many depend on the dividend streams to supplement their retirement incomes.

European IOC CEOs may be looking down the road to an even less hospitable view of oil and gas companies on the continent. Next year, France will ban investment funds operating under the ISR “socially responsible” label from owning shares in oil and gas companies that plan to grow their production. The investment label is voluntary, but France’s TotalEnergies might suffer since it plans to grow output by 2%-3% a year through 2028. BP and Shell could also suffer to the extent that these French funds own those shares.

Another problem for BP and Shell in seeking a U.S. stock market listing as a solution to their undervalued shares is their management record in recent years. Both BP and Shell cut their dividends in 2020 in response to the economic problems from the pandemic while ExxonMobil and Chevron did not. Thus, American investors are likely to question the security of future returns from the European IOCs, which likely will limit an improvement in their valuations. No one knows how long investor memories last about management decisions that harmed shareholder returns.

According to Shell Chairman Ben van Beurden, the company might benefit from a New York Stock Exchange listing after rejecting such a shift in 2021. Current Shell CEO Wael Sawan says this is not being actively discussed, but he has talked extensively with the media and investors about his frustration with the stock’s valuation discount. BP management has just recently changed, so it is likely too early for the new CEO Murray Auchincloss to be focused on such a step. However, TotalEnergies is completing a study for its board of directors on the value of moving its stock listing to the U.S. It is due in September. The possibility of such a move is driven by the shift in the company’s shareholder base. About 40% of TotalEnergies shares are held by North American investors, up from 30% in 2012. Note our mention of the smaller valuation discount of TotalEnergies to its American competitors, which is probably in response to the company’s business model more closely mirroring those of ExxonMobil and Chevron.

We wonder how much the valuation discussion is driven by European CEOs’ observation of the larger compensation packages afforded to U.S. IOC CEOs. The FT reported that ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods earned $36.9 million last year, up $1 million from the prior year, while Chevron CEO Mike Wirth earned $26.5 million, some $3 million more than in 2022. Those pay packages compared to $9.9 million for Shell’s Sawan and $10 million for BP’s Auchincloss.

Compensation is often tied to the size of the company, and that is consistent in the U.S. ExxonMobil has a market capitalization of $480 billion while Chevron’s is $300 billion. They are much larger than Shell’s $230 billion and BP’s 110 billion market capitalizations.

A big difference between North American and European IOC CEO compensation plans is their reliance on “pay-at-risk” provisions. Stephen Diotte, compensation practice leader at the Bedford Group, a Calgary-based consultancy, was quoted by the FT. “If an executive has a good year the impact of the incentive payments on total compensation can be quite significant. And that upside for pay won’t be anywhere near as high typically for a European based executive.”

To demonstrate the point, ExxonMobil CEO Woods’ base salary was worth about $1.9 million, or roughly 5% of his total compensation package last year. The company had its second-most profitable year in 2023 with profits of $36 billion, only trailing its 2022 results. Thus, most of Woods’ pay package came from meeting and/or beating his metrics for earning bonuses.

Closing stock market valuation gaps with the American-based IOCs could be a big winner personally for European CEOs if their compensation packages have the right incentives. Such a scenario cannot be ignored in the CEOs’ thinking when considering moving their company’s stock listing to New York. A win for them would be a big win for their shareholders, which is the purpose of “pay-at-risk” compensation structures.

The decisions by BP and Shell to slash dividends in 2020 -- unlike CVX and XOM -- left a lasting bad taste for investors. Moreover, the lack of clarity in corporate strategy from "full speed ahead green" to "upstream ain't so bad after all" confounds us. The Euro Majors need to articulate clear strategy and meet performance goals for earns and dividends.