Energy Musings - March 24, 2025

The issue of U.S. shipbuilding capabilities is gaining notice. While the focus is currently on building ships for the U.S. Navy, the industry's problems are also an issue for our commercial fleet.

U.S. Shipbuilding Status Of Greater Concern

The issue of the shipbuilding capacity of the United States is bubbling up into the public’s consciousness. Most of the concerns come from people involved with the U.S. military. They are concerned because our Navy’s fleet is smaller than China's naval fleet, our prime global competitor. While our fleet is superior in many ways, larger fleets have historically won wars of moderate or long duration. And China can build ships considerably faster than the U.S.

A new paper published by Foreign Affairs asks, “Does America Face a ‘Ship Gap’ With China?” Stephen Biddle, a Professor of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and Adjunct Senior Fellow for Defense Policy at the Council on Foreign Affairs, and Eric Labs, a Senior Analyst for Naval Forces and Weapons at the Congressional Budget Office, authored the paper. They possess the credentials to assess the question they pose, which is of growing concern among naval officials and now the White House.

While the paper’s question focuses on the military side of our maritime industry, assessing whether our commercial maritime industry faces a similar challenge is appropriate. Why should we be concerned about the private commercial shipping industry? Isn’t it more important for national security that we don’t trail our leading adversary?

Before answering those questions, let’s review the key points of the Foreign Affairs paper. It begins by noting that twenty years ago, the U.S. Navy had a battle fleet of 282 ships compared to China’s 220 ships. By the 2010s, the U.S. advantage had disappeared. Today, our Navy’s 295 ships trail China’s 400 ships.

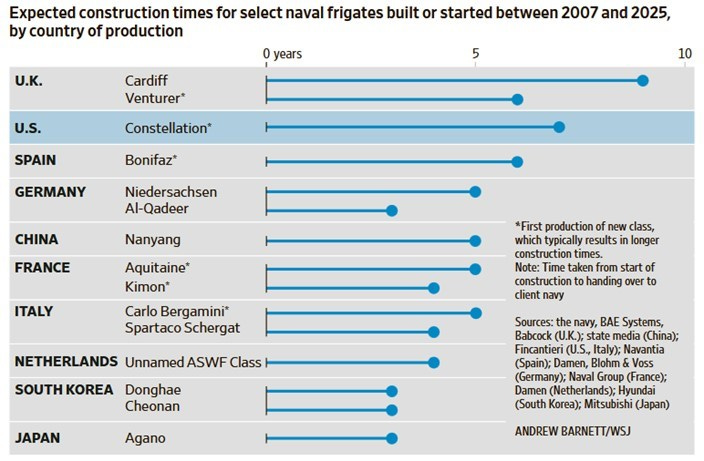

The Wall Street Journal authored an article about the construction problems of a new class of Navy frigates, years behind schedule and millions over budget. Much of the problem lies with changes the Navy wanted in the ship’s design. However, the ship’s construction delays demonstrate other U.S. shipbuilding shortcomings and why other countries elect not to buy ships from the U.S.

The WSJ analysis showed that of 20 different frigates built or being built around the world, all but one were or will be built in less time than the U.S. Constellation. Frigates are medium-sized warships used for submarine hunting and escorting larger naval ships.

U.S. Navy frigate experiences the second-longest construction time.

For the Navy to meet its most recent fleet growth plans ‒ going from 295 ships today to 390 by 2054 – and taking into account projected retirements means the shipbuilding industry must deliver substantially more ships than they did in the past decade, according to a report from the Congressional Budget Office. That report also predicts the construction cost will be about $40 billion annually over the next 30 years, or 17% more than the Navy estimates.

Regarding naval ship capabilities, as mentioned previously, U.S. ships are typically larger and have superior sensors, electronics, and weapons compared to China’s ships. We have more aircraft carriers and larger, more powerful ships such as cruisers and destroyers. Our submarine fleet is nuclear-powered, far more operationally capable, and equipped with more missiles than China’s mostly conventional diesel-powered submarine fleet. Moreover, our ships are operated by better-trained crews and are commanded by more experienced officers.

While our Navy fleet is qualitatively better than China’s and has superior seamen and commanders, our ability to replace lost ships is a huge concern. Many people are familiar with our vast shipbuilding capability during World War II. The Foreign Affairs paper’s authors noted this capability and its importance in winning the war. “It [the U.S.] launched so many new ships that year after Pearl Harbor, it was able to more than double the size of its fleet, even as the navy continued to absorb major losses. By contrast, Japan’s limited industrial capacity could only barely replace what its navy was losing in battle, let alone increase its fleet.”

The difference in shipbuilding capability between Japan and the U.S. influenced the fighting strategy of both combatants. Japan recognized the greater industrial capability of the U.S. However, it thought that surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor and elsewhere throughout the South Pacific could cripple the U.S. Navy’s fighting force. Japan believed combining high-quality ships and highly trained sailors would enable quick victories. By establishing a chain of island fortifications throughout the South Pacific, Japan hoped the U.S. would be dissuaded from fighting and agree to an early end to the war on Japan’s terms. We know that did not happen. As the war lasted longer than Japan expected, its inferior industrial capacity became a critical weakness that fore-ordained its loss.

The authors identified a critical weakness in our naval shipbuilding industry – it has become less efficient. While modern warships require longer to build than their World War II versions, the length of time has become substantial and has increased during the past 15 years. An aircraft carrier needs 11 years to be delivered and nine years for either a nuclear attack submarine or a destroyer. In World War II, we could build an aircraft carrier in a little over a year and a submarine in months.

According to the experts, China’s latest naval ships are now “in many cases comparable” to U.S. ships. That is because China is “quickly closing the gap” with the U.S. over ship design quality. China is building more aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines, and in roughly half the time it takes the U.S. to build similar ships. This is where China’s vast shipbuilding capability can tip the scale. It has the world’s largest shipbuilding industry. It delivers more tonnage a year than the rest of the world combined. The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence says that China’s shipbuilding capacity exceeds that of the United States by a factor of more than 200.

Most of China’s shipbuilding capacity is directed at commercial shipping, and modern warships are more complex to build. However, these commercial shipyards could quickly learn to build military vessels in a long war. That provides China with a tactical strength that is lacking in the United States.

Setting aside the military angle, the message of this paper for our leaders is that China’s commercial shipbuilding capabilities and its ship design and quality improvements should be a strategic concern. The most recent compilation of the history of U.S shipyards (2022) capable of constructing large ocean-going vessels shows 20 active shipyards and 60 inactive ones. Five of the 20 active shipyards are devoted to building large vessels for the U.S. Navy, while the remaining 15 are building U.S. Coast Guard and commercial vessels.

A 2024 compilation of large active shipyards building ocean-going commercial ships totaled 131. We do not have access to the list of shipyards, but we doubt all 15 U.S. large shipyards are included in that global list. Based on our knowledge of the large shipyards in the U.S., we estimate only 3-5 are included in the worldwide list. That means U.S. shipyards represent, at best, slightly under 4% of global active large shipyards.

It is essential to understand that our commercial shipping fleet plays a critical role in global trade and supports the economic growth and health of the United States. Moreover, commercial ships have played important roles throughout our history in times of war. A history of U.S. maritime policy from the founding of the U.S. until the passage of the 1920 Jones Act documents times when commercial ships were needed to help in the U.S. Navy’s efforts in fighting wars. As part of this documentation, the author also shows how commercial fleets helped other countries, such as the U.K. and France, with their large naval fleets during wartime. Large commercial fleets prevented opponents from extorting the countries, which can happen to nations that depend on foreign shipowners for their goods.

For readers interested in a detailed history of U.S. maritime policy, we recommend Journey to the Jones Act – U.S. Merchant Marine Policy 1776-1920 by Charlie Papavizas. This book is a highly detailed discussion of our nation’s maritime policy with over 2,000 footnotes and much more.

We are encouraged that the Trump administration has recognized the strategic vulnerability of the U.S. because of our limited shipbuilding industry. President Donald Trump has signed an Executive Order to create an office for shipbuilding in the White House. The office will deal with various policy prescriptions, including adding new shipyards, growing our commercial shipping industry, and training new U.S. mariners. However, the challenges are enormous.

In a recent report on U.S. shipyards, consultant McKinsey highlighted their sorry state. The analysts found metal casting equipment, cranes, and transport systems that were decades old—some of the equipment dated from before World War II. Equipment breaking down slowed construction times. In some cases, equipment replacement parts had to be fabricated from scratch because the units were so old parts were not available commercially. European naval shipyards typically have more modern equipment than U.S. shipyards. We do not doubt that this is even more true in Asian shipyards.

Added to aged equipment is the shipyard worker challenge. Developing a skilled shipbuilding workforce is necessary for the industry to accelerate its construction pace. The Navy blamed inexperienced workers for faulty welding on 26 vessels built by Huntington Ingalls Industries shipyard in Virginia. Quality problems add to construction times and inflate vessel costs.

Since our nation’s founding, we have benefited from the protection afforded us by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. These oceans also supported the nation’s growth through commercial trade. However, because of the lower cost construction of ocean-going vessels available elsewhere, the U.S. shipbuilding prowess that won World War II has been allowed to atrophy. Correcting this vulnerability will take decades, but we must start the effort now.