Energy Musings - June 30, 2025

The 12-day war between Israel and Iran, with U.S. participation, caused oil prices to spike as fear about the Strait of Hormuz being shut gripped markets. We are not in a more volatile oil market.

Risk On; Risk Off – Oil And Markets

On Friday, June 13, the day Israel staged its initial attack on Iran, Gillian Tett, a columnist and member of the editorial board of the Financial Times, wrote her weekly column titled “Oil in the new age of volatility.” She described the financial community's tradition of “casual” Fridays during the summer. By “casual,” we are not referring to the dress code, but rather the tendency to turn Fridays into three-day weekends by working from home or at beach, lake, or mountain houses.

As the news of Israeli air strikes spread, she said, financial players rushed back to their offices to “prepare for the inevitable storm.” By that, she meant they expected stock, bond, and commodity markets to react. Oil prices surged, initially by 13%, before settling up 7%. Higher oil prices sparked fears of increased inflation, driving bond yields higher. U.S. stock futures fell.

Although Iran produces only 3.3 million barrels a day of crude and exports 1.7 million, the threat financial players worried about was Iran’s ability to shut the Strait of Hormuz, a 20-mile-wide channel connecting the Persian Gulf with the Gulf of Oman, through which about 20% of the world’s oil and significant amounts of its natural gas flow daily. Shutting off that oil artery could have a profoundly negative impact on the global economy.

Iran has waved this oil card in the past, although it has never closed the strait during political crises. However, there is always a first time. The closest to a closure was during the 1980s Iran-Iraq war, when the strait was mined. During that period, there were 450 attacks on ships, but oil continued to flow.

Merely waving the oil card is sufficient to increase oil prices (risk on), just as it is now. Tett quoted research from ING Barings about its worst-case scenario — a prolonged blockage of the strait, which would lead to oil prices doubling to a record high of $150 a barrel later in the year.

Never fear, Tett, who created Moral Money, the Financial Time's sustainability newsletter, brought some good news to readers. She reported that a significant but “oft-ignored” development is that the “oil-intensity” of the global economy has declined. Oil intensity refers to the amount of barrels needed to power a unit of growth. According to the World Bank, in 1975, 0.12 tons of oil equivalent were required to produce $1,000 of GDP. By 2022, it had decreased to 0.05. She attributed the decline to “spreading renewable energy sources, like solar, and rising industrial efficiency.”

Indeed, we have learned how to build more efficient equipment used in everyday life that helps reduce oil demand. However, if renewables were a major contributor to global energy, their share of total primary energy would exceed 14.6%. Oil consumption continues to rise in lockstep with increasing GDP. Furthermore, the annual growth in fossil fuel use exceeds that of renewable energy. That is why there is no energy transition.

Tett’s message was that oil is not only moving into a more volatile world, but investor psychology is, too. To support her view, she quoted investment firm Pimco, which told clients, “The traditional world order ‒ in which economics shaped politics ‒ has been turned on its head. Politics [are] now driving economies.”

A week later, Tett was musing about the concept of “social silence” and why the stock market seemed unfazed by the ongoing war between Iran and Israel. At the time, there was considerable speculation about whether the U.S. would join the battle. For Tett, the stock market’s 20% rise since President Donald Trump’s “liberation day” tariff announcement reflected a lack of investor panic. She didn’t buy the Trump Taco explanation (Trump Always Chickens Out on his threats). Instead, she focused on the problem of “time lags.” In a world accustomed to instant responses to actions, Tett cited numerous studies suggesting that the impacts of economic policies and military threats occur farther in the future, such as in 2026 or later.

When she wrote her second column, Tett was perplexed that oil prices were only around $75 a barrel and the stock market had not crashed. She believes the various markets – stocks, bonds, oil – reacted to investor silence, which she warned could change quickly. Little did Tett know that less than 48 hours after her column was published, U.S. B-2 bombers would attack three significant sites of Iran’s nuclear program. The U.S. involvement in the Iran-Israeli war, Iran’s token response, and Trump’s brokered ceasefire radically changed investor outlooks in a matter of hours.

What happened in the oil market was instructive of how traders react to geopolitical events that threaten to disrupt conventional supply and demand expectations. The Financial Times published an article containing this chart detailing the oil price response to the 12-day war.

The short-term spike in global oil prices.

While Iran was shooting its pre-warned missiles at the U.S. military base in Qatar, in response to the U.S. attack, oil traders in London were aggressively selling futures and driving the price of oil back to where it was before the Middle East exploded. It only took seven minutes for the decline to begin. The Financial Times documented the rapid decline in the oil price.

5:30 pm: The oil price slide begins.

5:50 pm: Oil prices fall by 3%.

7:30 pm: Oil prices fall 7.2% to $71.48, the largest daily decline in three years.

The FT reported that traders were examining satellite images of the U.S. base in Qatar, which showed that all the planes had been removed. This convinced them Iran’s response was symbolic and it would not shut down Hormuz. The paper tiger response allowed traders to focus on the abundant oil supply, with the possibility that demand would weaken as global growth forecasts were revised downward.

Traders often use derivatives to accentuate oil price trading moves. These leveraged trading vehicles become significantly more valuable when oil prices rise or fall toward a preset target. In this case, with oil markets under pressure prior to the risk-on war trade, producers were purchasing “put” options, which pay out if crude oil prices fall. Producers were hedging their cash flows in anticipation of a potential collapse in oil prices.

Dealers manage these put trades by purchasing futures contracts, which serve as the vehicle for setting global oil prices. Ilia Bouchouev, a former president of U.S. commodity trader Koch Global Partners, told the Financial Times, “As Brent fell, the probability rose that the dealers would have to pay out. So, they had to sell more and more futures.” He suggested that this additional selling contributed to the sharp decline in oil prices. A trader at Marex, Al Munro, said, “There was a mad rush to the top and a mad rush down.” As often happens, the climb higher takes much longer than the elevator ride down.

Now that the war-inspired oil price spike is a thing of the past, two questions remain. Are we shifting into a new era of more volatile oil prices, and what could this market disruption mean for future oil prices?

When the world speculated that Iran might close the Strait of Hormuz, Amrita Sen of Energy Aspects wrote about the long-term impact of oil supply disruptions from geopolitical events. At the time, there was much about how the war might impact Iran that was unknown, but needed to be factored into scenarios for future oil markets and oil prices. Would the world lose access to Iran’s oil production or just its exports? What might the impact of a regime change be on Iran’s oil industry? Could a change happen quickly with little economic and social disruption, or might the country degenerate into a civil war? Each scenario could have dramatically different impacts on global oil supplies. Sen included in her article the following chart, which shows the long-term impact on oil supply from major geopolitical disruptions, such as the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the 1991 Gulf War, the 2002 Venezuelan coup, and the 2011 Libyan civil war.

Major OPEC political disruptions and the impact on oil supplies.

Sen noted that while the details of each crisis are different, the response is similar – instability threatens output for years, often resulting in higher oil prices for varying periods. This suggests the loss of Iranian oil supplies for an extended period would significantly tighten the global supply picture and support higher prices. This possibility could not be ruled out, but at the time, it was not considered the most likely scenario. That assessment proved prescient.

The greater impact may be on risk-pricing for oil in the future. The most recent period in which the market added a risk premium to oil was during the initial phase of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, when that battle evolved into an extended war of attrition with minimal impact on the global energy market, complacency about supply negated the need for a risk premium.

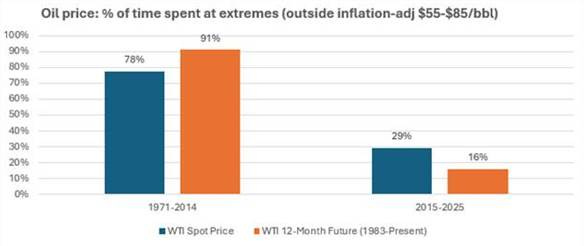

With short memories, the following chart, showing oil price volatility over the past 55 years, is enlightening.

Shale has made oil less volatile.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), World Bank, Energy Information Agency (EIA), St. Louis Federal Reserve (FRED), Bloomberg, Recurrent research.

The chart comes from Recurrent Investment Advisors LLC, which manages the Recurrent MLP & Infrastructure Fund. Recurrent has published several research reports outlining how the shale revolution has changed the global oil market. Their point is that before shale, OPEC supply actions during 1971-2014 created oil “supercycles,” keeping inflation-adjusted prices above $100 or below $50 for much of the period from 1970 to 2024. Prices remained outside an inflation-adjusted $55-$85/barrel range 80% of the time.

Starting in 2015, when the shale revolution shifted from natural gas to oil fields, the oil price became less volatile. Despite massive industry disruptions, oil prices remained outside the $55-$85/barrel range only 30% of the time between 2015 and 2025. Recurrent’s analysis found that WTI futures, which are less sensitive to oil’s physical constraints and more reflective of supply and demand dynamics, remained within the $55-$85 range almost 90% of the time. They also found that the oil cycle time was under two years from peak to trough, contrary to the earlier era when supercycles lasted for years.

Recurrent’s view is that too many market forecasters remain wedded to following the nuances of OPEC oil policies rather than the new dynamics of the oil market driven by America’s shale output. Those analysts who follow OPEC have been proven wrong repeatedly. Although OPEC output exceeds America’s shale, its production is more elastic and price-sensitive. Therefore, shale can become the marginal supply. Its shorter cycle time also helps undercut the extreme scenarios of $100 becoming the new floor price, or oil prices never recovering from their 2020 collapse.

The firm’s message is that any scenario forecast that extends beyond the 12-18 month response time for shale is doomed to be wrong. Therefore, they argue that investors should not invest based on the likelihood of prices falling outside the $55-$85 per barrel range. While the occasional spike up or down could provide investment profits, such a strategy is high-risk. It is better to focus on those oil and gas companies that benefit within the price range.

The dynamics of oil supply and demand remain challenging. Global economic conditions are uncertain. What we do know is that oil prices in the $60s will limit producer capital spending. We are seeing that now. Investors continue to demand that management return capital and refrain from overinvesting in new production. Meanwhile, the world’s population continues to grow. Moreover, billions of people want higher living standards, which requires increased energy. Rising demand and constrained supply ultimately lead to higher, sustainable oil prices.

Similarly, geopolitical tensions will continue to be a key consideration in investment decisions. Pimco’s view that politics, rather than economics, is driving the world order now remains to be seen. However, we are sure that shale has altered the global oil market. Long-term supply and demand dynamics continue to be the key to future oil prices, a relationship that remains unchanged. Expect higher oil prices down the road.