Energy Musings - June 10, 2024

The LCOE of wind has been and continues to increase. But the push for larger turbines has accentuated the quality issues pushing up costs. Wind's glory years had low interest rates but no more.

Wind Energy Performance Problems – Part 2

In Part 1 we dealt with the need for more high-tension transmission lines to move the wind power generated in areas where conditions are favorable to when it is needed. The need to grow transmission capacity, compared to the industry record of miles of lines constructed, suggests the needs will never be met. But we also spent time discussing the wind stilling issue and whether that was responsible for the decline in wind power generation last year in the U.S. We noted it was also possible that we located much of the six gigawatts of new wind capacity added to the U.S. industry is being located in areas where wind speeds are much lower.

There are other challenges for wind developers and utilities relying on wind power to meet their state clean energy mandates. One challenge is the cost of wind power, while the industry is also struggling with wind turbine quality issues.

Subsidies are the lifeblood of renewable energy. While its proponents proclaim that wind and solar power are the cheapest forms of power, the reality is that when the full system cost associated with them is considered, they become more expensive. That is because system costs include additional transmission expenses, backup power supplies, subsidies, and the costs to comply with state clean energy mandates. Those costs are not factored into the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) which divides the full cost to generate power (cost to build and install, the operating expense, repair and maintenance expenses, and the cost of capital and debt used to finance the project). Two key factors in the calculation are the capacity factor (how much energy will be produced compared to its theoretical maximum output) and the project’s life.

Renewable energy advocates use LCOE to sell the concept that their power sources are cheap. However, wind and solar power are intermittent. They depend on nature for their fuel. Thus, responsible analysts warn users not to compare the LCOEs of power sources that are not all dispatchable – can be produced and sent to consumers on demand – with intermittent ones – are available when nature produces them. Still, these comparisons are made.

An important difference between dispatchable and intermittent energy sources is that the former has a fuel cost but a lower capital cost, even though renewables charge nothing for their fuel but have much higher capital costs. This distinction has become a serious problem for many renewable energy projects as inflation drove up costs including the cost of debt that is aggressively used to increase their financial returns. Higher interest rates also inflate the risk premium associated with the equity component of renewable energy projects.

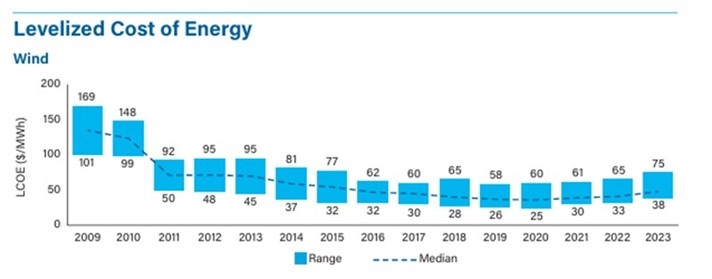

The 2023 annual market report of American Clean Power contained the chart below showing wind’s LCOE for 2009-2023. The chart is based on LCOE forecasts by BNEF and Lazard, two of the leading providers of this calculation. The chart shows wind’s LCOE dropping sharply in 2011 and slowly declining until 2019. Starting in 2020, the average of the high and low price estimates tics up slightly, beginning a pattern continuing to 2023. Based on media and analyst reports, the 2024 LCOE estimate will be higher, also.

After years of decline and forecasts the decline would continue, LCOE of wind has been rising and looks to continue going up.

The 1Q2024 American Clean Power market report presented the following chart of the annual and cumulative land-based wind capacity since 2000. We noted two interesting points. First, the cumulative installed capacity grew very slowly during the 2000s but then accelerated after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. The following years saw frequent expirations and revivals of the wind production tax credit subsidy. That subsidy was important in the economic analysis of wind projects and the erratic pattern of annual capacity additions in 2010-2019 reflects that environment.

Annual wind capacity additions have been declining since 2020.

Another factor involved in the economics of the wind industry helped it grow. It was low interest rates. To revive the U.S. and world economies after the financial crisis, monetary authorities cut interest rates to near zero and kept them there until the inflation eruption in late 2021. The impact of low interest rates cannot be underestimated in the sustained growth of wind capacity given the capital-intensive nature of wind projects.

That all changed when accelerating inflation forced the Federal Reserve to hike interest rates rapidly. Previously economic wind projects became uneconomic. The changed economic environment’s impact on wind projects can be seen in the data for annual offshore wind procurements and then cancellations.

The U.S. offshore wind industry has lost a substantial amount of previously contracted capacity.

The offshore wind projects canceled represented 35% of all procurements of 2017-2024. Those cancellations were made because the economics of these projects had changed materially when the cost of debt soared. Additionally, the procurements in 2024 were made at sharply higher costs. Many of the cancellations last year and this year were projects contracted in the past when interest costs and inflation were much lower. That shows how low-profit wind projects can be upended by any increase in costs not anticipated. The economic issue will continue to haunt wind projects for the foreseeable future.

The other major issue wind developers and their customers are dealing with is quality problems with turbines. The internet is rife with pictures and videos of wind turbine blades falling off, turbine nacelles catching fire, wind turbine towers buckling from strong wind gusts, and icicles hanging off the blades in winter. These are problems caused by equipment quality, age, maintenance, and exposure to extreme weather events.

Addressing the first issue of equipment quality, the recent decision by GE Vernova’s wind division to stop the development of its 18-megawatt (MW) offshore wind turbine created havoc within the industry. The decision was driven by the continuing losses experienced by wind turbine original equipment manufacturers (OEM) responding to customer demands for ever-larger turbines. Developers want larger turbines to harness greater volumes of wind power and lower the per-megawatt cost. This push led to OEMs designing and selling larger units before testing them. This pattern was to meet developer demands so they could compete in bidding contests by offering lower-cost units.

The business strategy led to increased warranty claims from faulty manufacturing and designs. According to a study from Wood Mackenzie, big wind turbine OEMs warranty provisions averaged 5.4% of revenues in 2023. That is up from 2.8% in 2018, but down slightly from 5.7% in 2022. The study did not include Siemens Gamesa, whose parent Siemens Energy set aside a provision of nearly €2 ($) billion for warranty and onerous contract costs. The set-aside equaled 22% of Siemens Gamesa’s 2023 revenues and 6.3% of Siemens Energy’s revenues.

Vestas, another leading wind turbine OEM, said 1Q2024 warranty provisions amounted to 4.5% of revenues. It exceeded the company’s target of 3%. Last year, Germany’s Nordex, an OEM, said its warranty provision was 5.5% of revenues in 2023, up from 4% in 2022. These large warranty provisions are hurting company profits, as well as supply chain and inflation issues.

We were also interested in data from Vestas about its “lost production factor.” That is a measure of reliability across the more than 40,000 turbines it has under full-scope service. The company deemed the performance “unsatisfactory” during 1Q2024, although it has declined since 2022. Vestas’ chief financial officer told investors the company was “not seeing any big new [warranty] cases.” However, it is still dealing with 2020 cases. Vestas also noted that inflation and delivery times have pushed up repair costs.

Vestas’ chief executive told the Financial Times that he had been concerned about seeing some component failures late in turbines’ life cycles. He said the company was working with its partners to resolve the issues.

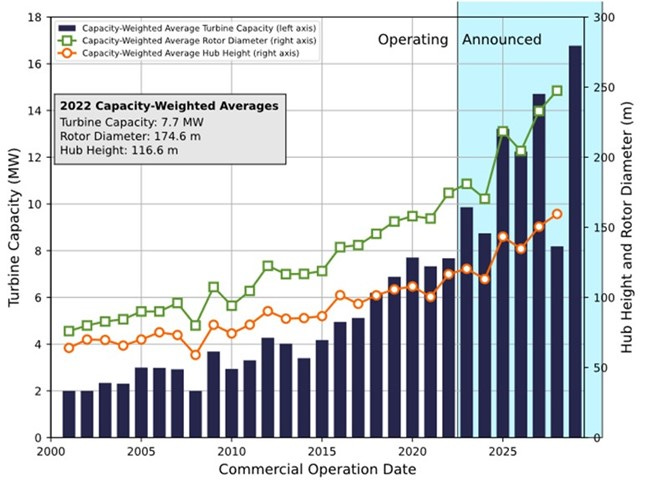

GE Verona, by concentrating on its existing wind turbine designs, hopes to improve its manufacturing efficiency. Such an improvement should improve profit margins following the recent years of large losses. Ending the race to build ever-larger wind turbines, especially for the offshore market, will upset the planning of some projects. It will also change the trajectory of growing average sizes for wind turbines in the following chart from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Offshore Wind Market Report 2023. The chart was prepared for the report, which was issued in mid-2023.

Turbine capacity has grown and may explain why manufacturers have suffered high warranty claims.

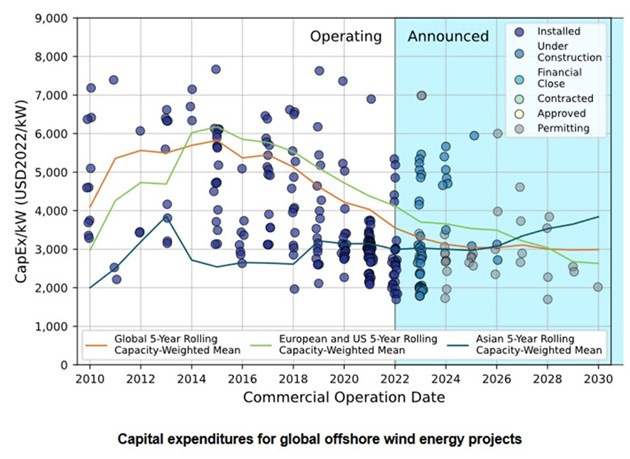

Another chart about global offshore wind cost dynamics offers some interesting data points to consider. The chart shows five-year rolling capacity-weighted means for the Asian, European, and U.S. markets, and the global average.

Rising Asian capex costs offset declines in Europe and the U.S keeping the global average flat.

We thought it interesting that the Asian line shows capex cost rising beginning in 2026 and climbing to an average comparable to its 2013 high. On the other hand, the European and U.S. line continues to fall and bottom in 2029. Combined, the global line bottoms in 2025 and remains essentially flat until 2030. Preparation of this chart relies on 2022 data, which does not reflect the market turmoil from high interest rates and inflation that have raised U.S. and European financing costs and equity risk premiums. We assume these conditions have impacted the Asian market, also. Therefore, this chart reflects the most optimistic near-term scenario for the cost of offshore wind power.

While many wind power proponents believe the economic wind storm that upended the market last year has passed, we would caution them that massive industry economic disruptions seldom are eliminated quickly. The subsidy costs for wind power are rapidly growing in many markets and the public is just becoming aware of how much their future power costs may increase. Based on the number of public protests over expensive energy and government mandates restricting their energy choices, it appears the industry’s landscape is far from settled.