Energy Musings - July 7, 2025

Offshore wind has become a legal battleground. We decided to update our performance charts on the two longest operating wind farms. We have added a chart for the newest wind farm.

Updating Offshore Wind Performance

We decided to update our charts on the performance of U.S. offshore wind farms. Three wind farms are currently operating, and four are under construction. One of the operating wind farms, Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind, is a pilot program that comprises two experimental data-gathering wind turbines that will become part of the larger wind farm currently under construction.

The pause in wind farm permitting ordered by President Donald Trump in January is being challenged in court by a consortium of 17 state attorneys general. They want the ban lifted so their states can pursue more wind energy. The suit is in a preliminary stage, as is a suit against the pausing and then restarting of construction of the Empire Wind I project. At issue in both cases is the question of the Secretary of the Interior and his regulatory agency (Bureau of Offshore Energy Management) following the provisions of the Administrative Procedures Act in governing their actions. With two federal district courts hearing cases involving the same question, a difference of opinion may result in the issue being sent directly to the U.S. Supreme Court for resolution.

It is impossible to know the offshore wind’s legal pathway, but we expect the journey will take numerous twists and turns over the next few months. We will be writing about developments as they unfold, but today we are interested in the latest data showing how these operating wind farms are performing.

Rhode Island

First up is the oldest operating wind farm – Block Island Wind (BIW), located off the coast of Rhode Island. Although BIW entered the offshore wind race behind Cape Wind, it crossed the finish line first. Cape Wind was initially proposed in 2001. The 170 wind turbines would be positioned in Nantucket Sound, five miles south of Cape Cod. Cape Wind was victimized by vigorous opposition from wealthy summer residents on Cape Cod, Nantucket, and Martha’s Vineyard, who wielded significant political influence. The opposition successfully killed the project after nearly a decade of effort. However, Cape Wind suffered from the emergence of operational issues that could not be easily or cheaply resolved. Some of these offshore wind operational issues persist, but regulators have chosen to overlook them in the current approval process. Could people die from their actions?

BIW’s five-turbine, 30 megawatt (MW) wind farm was developed by Deepwater Wind, an organization founded in 2007 by the financial hedge fund D.E. Shaw Group. The wind farm was designed as a test for larger wind farms anticipated to be built off the coasts of New York and Massachusetts. BIW is considered a success, despite never producing the amount of wind power its developer predicted. This is a story of how the goal post for performance has been moved, and a supportive media reports what they are told and nothing else.

In 2022, BIW celebrated more than five years of operation with federal, state, and local dignitaries attending an event hosted by the wind farm’s current owner, Ørsted. It acquired BIW and three additional offshore leases at the end of 2018 for $510 million. Deepwater Wind invested $300 million to build BIW, but that cost does not include the power cable connecting Block Island to the Rhode Island mainland. The cable was not part of the Deepwater Wind sale. The cable allows Block Island Power Company, the purchaser of BIW’s output, to ship surplus power to the mainland, while also being able to import mainland power when BIW does not produce sufficient electricity. The cable allowed Block Island Power Company to shut down its diesel generators when BIW began operation.

The Providence Journal’s science/environmental reporter attended the event and wrote a glowing report about BIW’s success. When we questioned its performance, we were informed that the reporter relied on data from the Public Utility Commission (PUC). He was uninterested in the press releases from Deepwater Wind and GE, the turbine supplier, that the wind farm would produce “over 125,000 megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity annually.” Multiple press releases quoting this number were issued when BIW sought to have its project approved by the PUC due to its high-priced electricity.

The PUC rejected the power purchase agreement as too expensive. That decision prompted an enraged Rhode Island legislature to write new standards for the PUC’s review of offshore wind projects. The historical cost-benefit analysis of power purchase agreements was banned. With the new standard in place, Deepwater Wind resubmitted its contract, and the PUC was forced to approve it, while noting in its decision that the approval ignored any cost-benefit analysis.

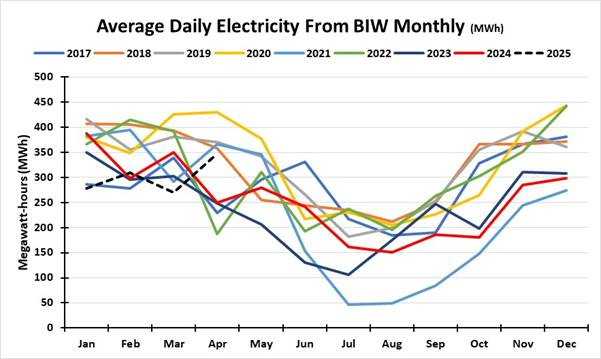

U.S. power plant operators, including those with solar and wind farms, are required to submit their monthly operating data to the Energy Information Administration, the statistical analysis and reporting agency within the Department of Energy. Their data is reported with a two-month lag. Therefore, we only have data for the three wind farms through April this year. The following chart shows BIW’s annual output for 2017-2024.

BIW has never achieved the output that Rhode Islanders were promised.

In the chart, we show the theoretical capacity factor (47.6%) for BIW based on the 125,000 MWh of annual output claims. No year has reached that threshold. The best performance was in 2020 when BIW reached 45.7%. However, Ørsted now says BIW’s theoretical capacity is 42%. They pointed to 2018-2020 as successful years, with 2017 being a start-up, but it nearly met the standard. The poor performance in 2021 was due to unscheduled major repairs for the turbines, especially the blades. We believe some of that repair work impacted 2022’s production. Ørsted’s problem is explaining why BIW’s performance was poor in 2023 and 2024.

Another way of looking at BIW’s performance is to examine the monthly output by year. The following chart illustrates the impact of the 2021 repair work. However, more importantly, it shows that in 2023 and 2024, the output was lower than in prior years during the winter months, when the wind blows stronger and steadier. It is during the winter months that Rhode Island Energy relies more on offshore wind to power the grid, thereby minimizing the need for expensive LNG and restarting coal and oil power plants to meet its generation needs.

BIW output is not off to a great start in 2025.

The first four months of 2025 show continued underperformance compared to virtually every prior year. April 2026 appears to be the first month that BIW output was closer to the historical high production for that month. It will be interesting to see if the May data shows a continuation of that better performance or a decline more in line with previous summer months.

Virginia

Moving down the coast to Virginia, we find a very different picture. Dominion Energy, Virginia’s primary electricity company, is building a massive offshore wind farm. Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind (CVOW) will have 176 turbines with a capacity of 2.6 gigawatts (GW) of power. It is located 24 nautical miles off the coast of Virginia Beach and began construction in late 2023. It is expected to be operational in late 2026.

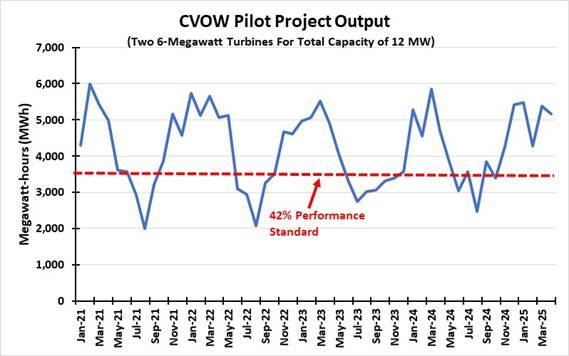

To gather data to help fine-tune the design of CVOW, Dominion installed two 6-MW turbines in 2020. The research project was also designed to help understand the challenges of turbine installation. These were the first turbines installed in federal waters, as BIW is located off Block Island in Rhode Island state waters. The turbines were installed on the western edge of the COVW lease.

Where the pilot wind turbines are located.

CVOW is the only offshore wind project being developed by a utility company. The approval process was contentious, involving multiple hearings and negotiations. The Commonwealth of Virginia State Corporation Commission (SCC) approved the project in the summer of 2022, but with several stipulations proposed by intervenors. The intervenors included two environmental non-government organizations (the Sierra Club and the Southern Poverty Law Center) and Walmart. These stipulations were considered non-starters by Dominion’s management, which led to subsequent hearings and negotiations among the parties.

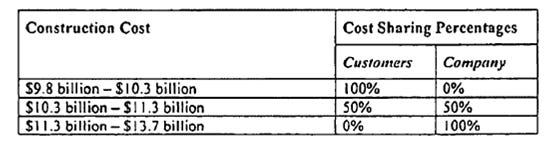

One issue was the estimated cost of CVOW and who would be responsible for cost overruns. The project was estimated to cost $9.8 billion. Dominion added a 5% contingency fund, boosting the project’s expected cost to $10.3 billion. Dominion’s $9.8 billion estimate included approximately $1.15 billion for interconnection and transmission facilities. The more telling number was Dominion’s acknowledgement that the project’s cost, including financing costs less investment tax credits, was estimated at $21.5 billion.

Given the magnitude of the project’s cost, intervenors representing the public questioned who would pay for future cost overruns. This is important because under Virginia’s utility regulations, a utility company earns a return on its assets, which include the proportion of CVOW’s construction costs already expended, as well as those that would be expended in the future. Dominion sought the most lenient cost-sharing formula, while the intervenors wanted the strictest. A compromise was struck and approved by the regulators that set forth the following cost-sharing arrangement.

The SCC determined that should the 176-turbine project’s cost “exceed $9.8 billion, and should any incremental costs be approved by the Commission as reasonable and prudent in a future proceeding, the Company voluntarily agrees to share responsibility for certain such incremental costs according to the schedule below.”

Virginia ratepayers are liable for $500 million of cost overruns.

The SCC further addressed what happens should CVOW’s total cost exceed $13.7 billion.

“There is no voluntary cost sharing agreement for any Project costs that exceed $13.7 billion. In the event that the Project’s construction cost estimate were to exceed $13.7 billion, the disposition of the Project will be determined in a future Commission proceeding and the stipulating parties agree that no construction costs in excess of this amount are entitled to a presumption of reasonableness and prudence; however, nothing prevents any party from arguing that construction costs in excess of $ 13.7 billion are reasonable and prudent.”

The key point is the issue of “reasonable and prudent.” All costs exceeding the original $9.8 billion estimate must meet this standard to be included in Virginia Electric & Power Company’s (Dominion’s operating company in the state) rate base under the cost-sharing agreement. We assume the SCC believes that a project costing 40% more than the original estimate reflects potential mismanagement by the company. Ratepayers should not be exposed to these costs unless the SCC determines otherwise about mismanagement.

Why is this issue important? Dominion has announced that the project’s cost has now risen to $10.7 billion, putting it into the 50/50 cost-sharing phase of the agreement. Two weeks ago, the company announced that its assessment of the impact of trade tariffs would add another $120 million to the project’s cost, pushing it slightly above $10.8 billion. While Dominion claimed it had locked in all project costs before construction began, it is already costing 9% more with 18 months of additional construction activity ahead.

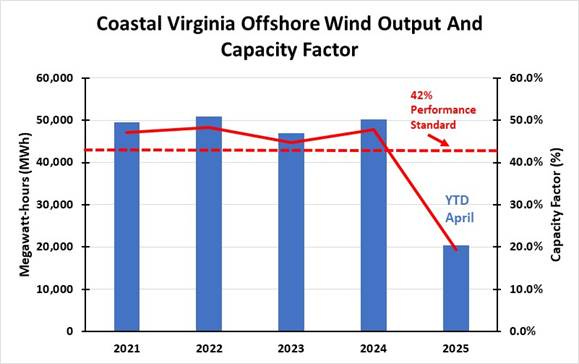

The chart below shows the performance of the two experimental wind turbines. Although these turbines represent only 12 MW, they are performing at a high level, well above 42%. This is significant because that performance standard nearly sank CVOW. The SCC, at the behest of the intervenors, initially included an annual performance standard for the project. It stated that CVOW would report its capacity factor annually, and if that measurement fell below 42%, the company would be required to explain the shortfall. They were also required to make up the power deficit at the company’s expense.

Interestingly, the 42% performance standard was below what Dominion claimed the wind farm would produce. It utilized higher outputs to demonstrate the reasonableness of the project’s cost. After the SCC’s performance standard was included in its approval, Dominion’s chairman told investors and analysts that the company would abandon the project if the performance standard stayed.

The intervenors and Dominion agreed to modify the calculation of the performance standard. The final agreement stated:

“Operating Performance Provisions: Beginning with the commercial operation of the Project’s final wind turbine, and extending throughout the thirty-year expected service life of the Project, the Company will report average net capacity factors for the Project on an annual basis in its Rider OSW update proceeding. To the extent the Project’s net capacity factor, as measured at the aggregate turbine level, is less than 42% on a three-year rolling average basis, the Company will provide a detailed explanation of the factors contributing to any deficiency.

“To the extent the Commission determines that any deficiency has resulted from the unreasonable or imprudent actions of the Company, the Commission may determine a remedy at that time to address any incremental energy or other costs resulting from such actions.”

If the wind farm fails to meet the 42% performance standard for a year, Dominion can hope that the three-year average keeps it above the threshold. Time is on Dominion’s side, and the likelihood of a three-year wind drought is low. Then there is the issue of how the SCC will measure the “unreasonable or imprudent actions” test.

Based on the performance of the two turbines, CVOW appears safe from falling below the performance standard. Of course, Dominion does not know how the actual wind farm will perform. Ratepayers should hope that the final CVOW performs above the standard, because the SCC said, “the electricity produced by this Project will be among the most expensive sources of power - on both a per kilowatt of firm capacity and a per megawatt-hour basis - in the entire United States.”

That is because this project is “the largest capital investment, and single largest project, in the history of the Company.” Moreover, it increases by 50% Virginia Electric and Power Company’s rate base. And it more than doubles the Company’s entire investment in generation rate base. The SCC said that “the magnitude of this Project is so great that it will likely be the costliest project being undertaken by any regulated utility in the United States.” That is an amazing statement given the Georgia Power Company’s Vogtle nuclear plant, which arrived seven years late, $17 billion over budget, and at a total cost of $36.8 billion. That is a story for another day.

CVOW’s pilot turbines are performing well.

The monthly performance of CVOW.

New York

The newest operating offshore wind farm, South Fork Wind, off the tip of Long Island, lacks sufficient data to make a judgment about its long-term performance. South Fork Wind has 12 wind turbines and a total capacity of 132 MW. The wind farm has produced high output during its initial winter months. However, its output was low during the summer months, which is when power demand on Long Island increases, and offshore electricity would be welcome.

South Fork Wind appears to be performing well, but it is early.

The blended power cost of South Fork Wind is $0.14 per kilowatt-hour, based on a blending of $0.16 for the first 90 MW of power and $0.086 for the remaining 40 MW. The electricity price increases by 2% per year for the 20 years of the wind farm’s power purchase agreement with New York State.

Conclusion

The newest wind farms – South Fork Wind and CVOW – are outperforming BIW. Given the geographic spread of the wind farms, it is impossible to determine the relative contributions of the different locales to the respective wind farm performances. Are the wind turbines of the newer wind farms of higher quality than BIW’s, or is BIW showing the impact of aging wind turbines? More performance data will be helpful, but the legal issues will dominate the discussion about future offshore wind farms. Buckle up for some exciting months ahead.