Energy Musings - July 30, 2023

Climate To Be Stock Market Theme Of The Decade?

Legendary stock market investor, Warren Buffett believes in long-term investing. He has said, “If you aren’t willing to own a stock for ten years, don’t even think about owning it for ten minutes.” That certainly isn’t the mantra of day traders or momentum investors. It isn’t the investment style of most active portfolio managers. In Buffett’s case, he often owns a stock for decades, and in some cases even buys the entire company to add to his Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate.

If you focus on long-term investing, your portfolio will experience ups and downs as the stock market oscillates through periods of optimism and pessimism about the future of the world’s economy and its impact on company earnings. Stock prices reflect the mood of investors and the earnings power of companies. But other factors impact share prices such as investment themes that drive investors to favor certain types of companies at any point in time.

We recently listened to a professional wealth manager interview the founder and managing editor of an independent global macro research and trading advisory firm with a focus on major investment themes. During the podcast, he was asked about what investment theme investors should be focused on now. Before answering the question, the strategist reviewed the history of investment themes. His narration covered almost all our investment career. We found his history of decade investment themes insightful as it characterized what was popular at the time and made money for investors until the theme stopped working. Often, investors fail to realize a theme has ended and another has begun, which is what costs them money.

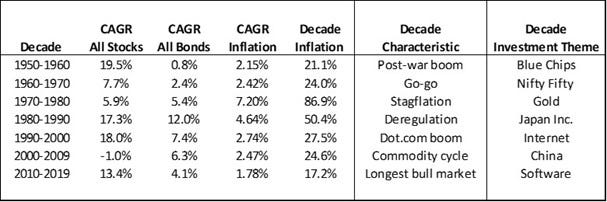

Every decade has had an investment theme that drove select stock or asset prices. Here is the record for 1950 to 2020.

Let’s look at the investment themes the strategist identified. To make the review parallel our career, we will begin with the 1960s, a decade the strategist didn’t mention. To understand the theme of the 1960s, we must first understand the 1950s. That market was an extension of the post-World War II boom driven by rapid economic growth as the U.S. transitioned from a war footing to one capitalizing on the many inventions of the late 1930s and during the war, rapidly growing young populations, and rising incomes and improving lifestyles. The public’s inability to spend on goods, cars, appliances, and homes during the 1930s and 1940s led to a buildup of savings which fueled the 1950s economy. But investing during that decade was heavily influenced by the conservative approach of Americans who had lived through the Depression and WW II.

The 1960s opened with the election of a wealthy, young Massachusetts senator, John F. Kennedy. His lovely and stylish wife, Jacqueline, and his young children, along with the large Kennedy clan, created a model of optimism and “vigor.” Not only were people able to benefit from the fruits of the past, but they were also encouraged to become more benevolent and involved in society. “Ask not what the country can do for you, ask what you can do for the country.” That line from Kennedy’s snowcapped inauguration speech set the decade’s tone.

The 1960s decade transitioned from the conservative 1950s era to the ‘go-go’ era and momentum investing that capitalized on rapid economic growth, rising incomes, and America’s vision of improving the lives of people around the world. The stock market was dominated by the “Nifty Fifty” stocks. This select group of stocks emerged from the holdings of Morgan Guaranty Trust portfolios and were known as “one-decision” stocks – one just had to decide to buy. Because of their growth prospects, company earnings would only go up, so being judicious in the price paid for the shares was of less concern than buying them to ride the momentum of that growth. Economic problems brought on by the ‘guns and butter’ clash between the Great Society and the Vietnam War ended this boom.

The decade of the 1970s opened with the Nixon administration’s decision to exit from the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971 cutting the dollar’s tie to the value of gold. This move contributed to a coalescence of international oil producers centered in the Middle East who began using crude oil as a weapon, since U.S. output had peaked, America’s oil imports were exploding, and America was backing Israel. Those producers saw the value of their oil output diminish as they were forced to take paper money rather than gold bullion. The oil shocks of 1973 and again in 1978 bookmarked the decade. Coupled with the massive dollar flows going to tiny Middle East kingdoms, higher oil prices, and the flood of paper money sparked a decade of inflation, marked by a weakening of the value of the dollar and soaring gold prices. Gold went from $35 an ounce to $850 over the decade!

Gold prices were pushed up by rapid inflation created by the oil shocks and the cost of redesigning economies. High inflation (the decade’s annual inflation rate was 7.2%) resulted in central banks fighting back to try to regain control over prices. Their weapon ‒ interest rates ‒ were hiked to unimaginable levels (21.5% in 1980) to snuff out demand. The corollary was rising unemployment rates as companies needed fewer workers as they faced weakening demand for their output. But as inflation’s fever moderated, consumption began rising and employment started climbing.

The gold era ended when the oil wars among Middle East producers broke out in the early 1980s and high interest rates caused recessions that undercut gold’s value as an investment. America’s deregulation era helped cut inflation in half, but the decade’s real story was the emergence of Japan Inc. as an economic powerhouse. Japan was seen as taking over the world’s economy because of its successful companies, which seemed immune to the economic and financial headwinds impacting others. In the 1980s, we became obsessed with how Japan’s economic and corporate management success could be mimicked. The soaring value of the Japanese yen enabled it to buy iconic New York and California real estate, only to see the nation’s fortunes wane as we entered the 1990s.

That was the decade of the Internet. Those early brick-like cell phones rapidly morphed into smaller, less costly, and eventually ubiquitous devices. Cell phones, desktop computers, and video games came to dominate our homes and businesses and quickly the investment scene. The Nasdaq provided a welcome home for the tech industry and soon we were immersed in the dot.com boom. The end of the 1990s was dominated by fear of the unknown – could our computer systems survive the calendar change from 12/31/1999 to 01/01/2000? Yes, Y2K. We survived the calendar change, but not the dot.com investment theme.

From a fascination with dot.com stocks, the market suddenly switched its focus to China as that nation emerged on the world stage nearly 30 years after Nixon toasted Mao Zedong in Beijing. In December 2001, China was welcomed into the World Trade Organization as it ramped up construction activity in preparation for hosting visitors from around the world attending the 2008 Summer Olympics. A commodity boom emerged driven by China’s infrastructure buildout. Soon everything was all about China because of its abundant and cheap labor supply, which, when coupled with access to substantial key raw materials for the high-tech and renewable energy industries, enabled it to become the manufacturer for the world. Global companies raced to build supply chains in China to capitalize on these favorable cost benefits. Improved operating margins resulted in outsized profits.

The high-tech revolution facilitated by China shifted into overdrive as we entered the 2010s. But suddenly the emphasis shifted from hardware to software. The decade’s investment theme was identified in a Wall Street Journal op-ed by Marc Andreessen. He identified himself thusly: “I am co-founder and general partner of venture capital firm Andreessen-Horowitz, which has invested in Facebook, Groupon, Skype, Twitter, Zynga, and Foursquare, among others. I am also personally an investor in LinkedIn.”

Andreessen wrote: “My own theory is that we are in the middle of a dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies are poised to take over large swathes of the economy.

“More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense.”

Since the start of the 2020s, the stock market, after being bounced around by the economic turmoil from the devastation brought by Covid-19 and the subsequent global economic recovery, has been marked by questions about high-tech company valuations versus other overlooked market sectors. While this question is preoccupying investors, the market strategist believes this decade will be dominated by climate. He specifically said, “Not climate change, but climate.” What does that mean?

The strategist surprisingly predicts that China will be the only country to meet its carbon emissions target. How could that be since China is building coal-fired power plants faster than anyone can count them? But it is also the world’s leading investor in new renewable energy capacity, as agencies such as IRENA point out. As the strategist said, this is a self-preservation issue. He asked: How good is it to become rich if you’re going to be dead? Improving China’s air quality, especially in its large cities, is a life-or-death issue. Since the country is an autocracy, making things happen in its economy and society is easier than elsewhere where governments must legislate, mandate, and persuade to effect change.

One way China will meet its emissions reduction target is by reducing its aluminum and steel manufacturing capacity. To the extent such a reduction is in line with China’s reduced internal needs, it seems possible. But if the reduction cuts global supply, then such a move could be inflationary. What people misunderstand is the cautious energy transition plan of China. As China’s President Xi Jinping, said, “carbon goals shouldn’t come at the expense of the ‘normal life’ of Chinese people or energy or food security.” He also stated, “We can’t toss away what’s feeding us now while what will feed us next is still not in our pocket.” Is this the climate change tortoise to the Western world’s hare?

We were shocked to hear the strategist’s observation, but it made us stop and think. Reflecting on the nature of the articles that populate our newsletter, we are shifting away from dwelling on the day-to-day details of the global oil and gas markets and spending more time analyzing and writing about non-fossil fuel markets and clean energy topics.

Climate is a ‘big tent’ concept. It covers not just the issue of fuel sources and supplies, but also how we reconfigure economies, our transportation systems, our food supplies, and even how we build our housing stock including our choices for heating and cooling them. While some people think climate is related to the commodity cycle, the strategist says not all commodities will benefit.

In our thinking, climate as an investment theme is not anti-fossil fuel or pro-renewable energy, it is both. We will need all forms of energy to power our world for decades given growing populations, longer lifespans, and rising living standards. Maybe we will find a magic energy source to replace our current system, but we will not hold our breath that it will arrive anytime soon. How much of each type of energy we use depends on the laws of physics and how we integrate and complement the use of each fuel. Maybe China’s approach is better – invest in both.

When one thinks about it, climate touches every sector of the economy, just as did each of the prior decade’s themes. It touches old established companies and technologies and spawns new ones. It will provide investment opportunities, but they may not always be obvious. It will change what we consider normal for our lifestyles. This reality will only be evident when we look back on the decade and as we consider the investment theme for the 2030s. Enjoy the journey.