Energy Musings - July 26, 2024

Airplane passengers flying in and out of New York metropolitan airports may not realize their lives may be at risk by the construction of hundreds of offshore wind turbines. Read about it.

Can Offshore Wind Turbines Kill You?

Can an inanimate, three-armed structure standing miles offshore kill you? Of course not. Oh, but wait. We have learned that offshore wind turbines can kill and people flying into New York City area airports could die. Should you worry? Yes, if you fly. You should worry because the federal government agencies approving offshore wind turbines have put adherence to the Biden climate change agenda above the safety of mariners and fliers.

Let’s step back and examine why offshore wind turbines have become a lightning rod in the battle to industrialize America’s oceans. There is little doubt offshore wind has undying support from climate activists. But it faces fierce opposition from people worried about their incomes, jobs, and safety. The single-purpose focus of regulators on installing thousands of offshore wind turbines while disregarding their danger, potential environmental damage, and high electricity prices is unconscionable. The recent disintegration of a Vineyard Wind turbine blade letting toxic and hazardous debris wash up on the beaches of Nantucket Island, an iconic American summer tourist location, is the latest episode raising concerns over offshore wind.

Offshore Wind History

Currently, offshore wind turbines are linked with whales and the increase in their strandings. However, before whales entered the debate, offshore wind faced intense opposition from East Coast elites upset about the towers ruining their ocean views.

The history of U.S. offshore wind is longer than many people realize. It didn’t start with the January 2021 Biden administration declaration to deploy 30 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030. That pledge resulted in the mobilization of federal agencies to accelerate the approval for and construction of thousands of East Coast offshore wind turbines.

Massachusetts Offshore Wind

In 2001, a small environmental group conceived of building a wind farm on Horseshoe Shoal in Nantucket Sound in federal waters between Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket Island. The project envisioned 130 wind turbines with a maximum capacity of 468 megawatts (MW) and an average anticipated output of 174 MW.

The plan, submitted to the Army Corps of Engineers, was to use Siemens 3.6 MW wind turbine generators with a hub height of 258 feet above the water’s surface and blades 172 feet long. The lowest and highest tip heights will be 75 feet and 440 feet, respectively, above sea level. The turbines were to be spaced across a 25-square-mile area of Nantucket Sound, a region dependent on tourism and fishing, which sparked fierce local opposition.

Cape Wind scored victories with approvals from federal agencies even after the Energy Act of 2005 resulted in permit responsibility moving from the Army Corps of Engineers to the Minerals Management Service within the Interior Department. The project overcame objections from the Department of Defense, the Federal Aviation Authority, Mitt Romney, the governor of Massachusetts, the Audubon Society, the Wampanoag Tribe, and local homeowners. Cape Wind successfully secured financing for the project whose cost escalated from $780 million to over $2 billion during the 17-year battle. The project was even able to pre-sell its power to two local utilities. In the end, the opposition overwhelmed the resolve and financial resources of the Cape Wind sponsors who relinquished the lease in 2018.

Texas Offshore Wind

During the Cape Wind saga, on another coast offshore wind was moving forward quickly. In 2007, Coastal Point Energy grew out of Wind Energy Systems Technology (W.E.S.T.), a company that applied for and secured leases offshore Galveston, Texas.

A legacy of Texas’ entry into the U.S. (it was a sovereign nation and entered via treaty) was its control over coastal waters out 9 nm (10 miles). A condition of joining the U.S. was for the state to retain its coastal waters. Thus, developers only needed to secure a lease from the Texas General Land Office. Because of navigational concerns, the project approval and permits would come from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Both regulators maintained quick approval processes, cutting the time to weeks and months rather than years.

In 2008, the Corps of Engineers approved the company’s installation of an offshore meteorological tower near an offshore oil production platform to gather wind data. Under that permit, Coastal Point was allowed to install a single 3-megawatt (MW) turbine.

Using the data from the meteorological tower and the knowledge gained from the single wind turbine, Coastal Point planned to build a 12 MW test wind project using four 3-MW offshore wind turbines. Ultimately, the company anticipated building a 300 MW offshore wind farm as part of a long-term plan to build wind farms on the company’s Texas coastal leases stretching Brownsville on the Mexican border to Beaumont near the Louisiana state line. The leases contained sufficient acreage to build 4.2 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity.

Coastal Point worked to obtain a power purchase agreement from Austin Energy, the municipal electricity company for the city of Austin, Texas. The company was already a supplier of onshore wind to Austin Energy, but the $40 per MW was inadequate for the economics of offshore wind. It was estimated the price needed to be twice the onshore price or $80/MW. That price was competitive with natural gas prices which were trading in the range of $7-$8 per thousand cubic feet. But the shale revolution was underway and natural gas volumes began to climb and prices to fall. At the same time, the cost of building the wind farm rose. Falling competitive fuel prices and rising development costs necessitated negotiating a higher electricity price with Austin Energy. A power purchase agreement could not be reached and the project died.

Rhode Island Offshore Wind

In New England, as Cape Wind’s battles were being waged, a group backed by a New York hedge fund was able to secure approval to build a demonstration wind farm off the coast of Rhode Island’s Block Island. The five, 6-MW wind turbine project was to showcase the advantages of a much larger wind farm to be built in federal waters off New York. The final stumbling block for Block Island Wind (BIW), as the project is called, was getting its expensive electricity price approved by the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission.

Since the island had no connection to a mainland power supply, it entertained the idea of a permanent connection. Block Island’s power was generated by diesel generators, which in 2015 resulted in residents paying 50 cents per kilowatt-hour (ȼ/kWh) for their electricity. Deepwater Wind, the owner of BIW, offered to supply the island with electricity for 27.5 ȼ/kWh with a 3.5% annual price escalation.

When the proposed power contract was presented to the PUC for approval, the commissioners rejected it because they found the price to be excessive. The proposed Block Island price was about three times the cost of electricity onshore in Rhode Island. As Deepwater Wind had the support of the entire Rhode Island political establishment including the governor, federal and state officials, and influential local politicians, the legislature re-wrote the state’s PUC rules. No longer could the PUC use a cost/benefit analysis for renewable energy projects built in the state. With the new regulations in place, the rate case was resubmitted and the PUC reluctantly approved it. In the fall of 2016, Block Island Wind began operations.

Offshore Wind and Whales

Offshore wind turbines have become a lightning rod because their construction has been associated with an Unusual Mortality Event (UME) for North Atlantic Right Whales. The Fisheries division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is responsible for implementing the Marine Mammal Protection Act. A provision of that act explains NOAA’s responsibility. A UME is “a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response.”

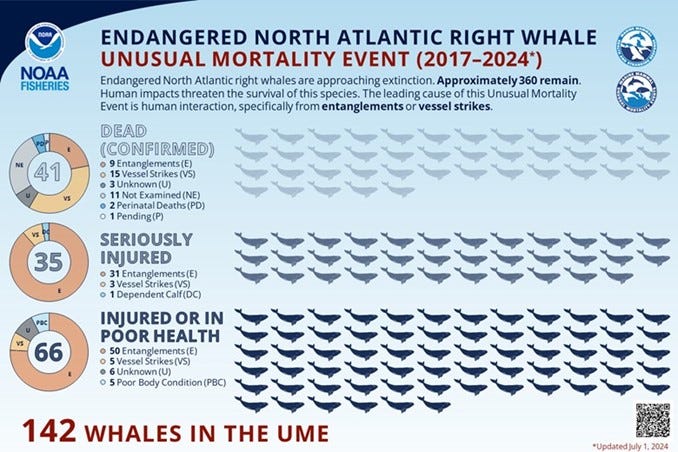

A UME for NA Right Whales was declared in 2017. Here is a chart from NOAA of the incidents of NA Right Whales. There are numerous explanations for the deaths, which is demonstrated by the details under each category of events.

NA Right Whales have suffered from an unusual number of deaths, experienced a large number of serious injuries, or are in poor health jeopardizing the population’s future.

We are not going to debate the issue of offshore wind turbine construction and whale deaths other than to say that there is more than circumstantial evidence of their involvement. We find it interesting that NOAA researchers say they do not have enough information to determine the relationship. However, the bureaucrats that head NOAA are quick to say “there is no proven link” between offshore wind construction and whale deaths.

Research in Europe has shown that loud underwater noise may cause mammals to become disoriented or even lose their hearing. Could that explain the increase in vessel strikes as whales are disoriented and swim into the paths of vessels, especially since vessel traffic has increased significantly in recent years? We do not know the answer but believe the question has received little attention and should receive more.

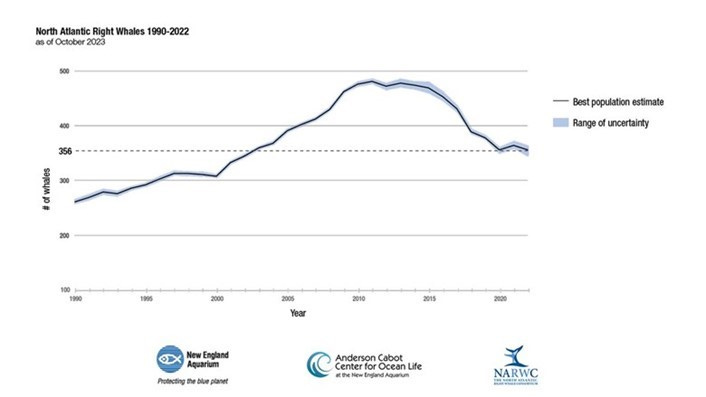

Here are why the NA Right Whale deaths are of great concern. After 20 years of a growing population of NA Right Whales, it peaked in 2010 and began to slowly decline until 2015-16. After 2016, whale deaths accelerated, scaring Fisheries officials and sparking the UME.

Since offshore wind activity began in 2015, NA Right Whale deaths have increased jeopardizing this endangered species’ existence.

The past few years show the NA Right Whale population plateauing. It has some mammal scientists optimistic that the worst of the UME is over. However, the head of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium, which produced the above chart, cautioned about that optimism. Dr. Scott Kraus, chair of the Consortium stated:

“We continue to injure and kill these whales at alarming rates, such that they cannot carry out basic biological functions like growth and reproduction. While the absolute population numbers are important, other indicators are discouraging. Until we implement strategies that eliminate injuries and deaths, and promote right whale health, this species will continue to struggle.”

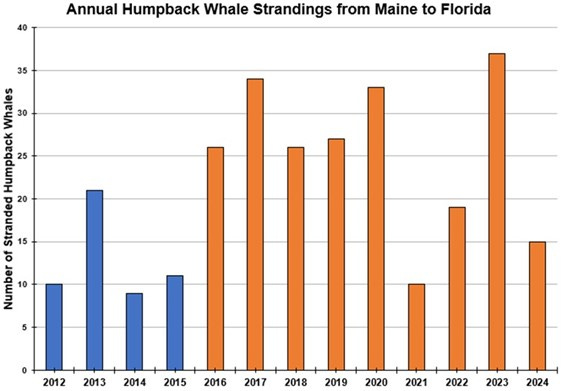

Dr. Kraus’ concern about whale deaths reflects not just the UME for NA Right Whales but the one for humpback whales. The chart below shows just how humpback whale deaths have increased in recent years. They have soared compared to the average number of deaths during 2012-2015.

Humpback whale strandings have soared since East Coast offshore wind construction activity began.

Environmentalists should be just as concerned over whale deaths, especially since NA Right Whales and Humpbacks are endangered species protected by federal law, as they are over carbon emissions. Since so little is known about the hearing ability of the whales that have died from vessel strikes along the East Coast, caution over offshore wind’s contribution to the UME is warranted. More research and a more measured pace of development are warranted. However, such caution goes against the Biden climate change agenda, and bureaucrats must obey their boss’s wishes.

FAA, Radar, And Offshore Wind Turbines

The FAA issue is scarier but has received little attention. The FAA objected to the construction of Cape Wind because it worried that the wind turbines would interfere with the radar system at Otis Air Force Base on Cape Cod. An agreement between Cape Wind and the FAA to fix the base’s system to ensure that it would not be affected by the wind farm earned the agency’s approval. We later learned there was no way to upgrade the radar system.

As East Coast offshore wind projects have moved through the approval process with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), we learned the Coast Guard will not be able to perform search-and-rescue operations within a wind farm because of interference with maritime radar systems. This means the Coast Guard cannot use low-flying helicopters in wind farms to search for missing vessels or people. Coast Guard ships cannot travel within wind farms because their radar does not allow discrimination between real and false signals of other vessels increasing collision risk.

When the radar issue emerged during the approval process for Cape Wind and no easy solution was available, federal agencies realized there was a potentially intractable problem. The radar interference issue came before Congress in 2006. The issue gained national attention when the Department of Defense (DoD) opposed the construction of the Shepherds Flat Wind Farm in Oregon because of radar clutter (i.e., false targets) from the wind turbine blades. The clutter was known to impair the ability to detect, monitor, and safely conduct air operations. As a result, the agencies, the White House, and Congress recognized the seriousness of radar interference.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Energy Musings to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.