Energy Musings - February 24, 2025

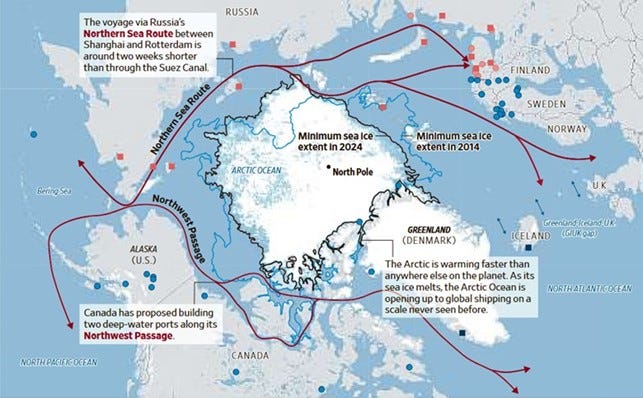

The world viewed from the North Pole shows the importance of Greenland. It also highlights the lack of deep-draft shipbuilding capacity in the U.S. Icebreakers are only the tip of the issue.

Icebreakers Spur Concern About Global Shipbuilding

Most of us grew up studying world maps like the one below. The map presents the world as flat, not the globe we know it to be. This map does not depict the world Columbus worried about falling off if he went too far west. It is flat because that was the only way people could envision the world.

The most popular presentation of the world.

However, looking at the world from the North Pole gives you a different perspective. One sees how close Russia is to the United States, Canada, and the Scandinavian nations. The map highlights Greenland’s geographic importance. It lies in the middle of all the countries bordering the Arctic Ocean.

One also sees how large Greenland is, although its size is due somewhat to the extent of the ice covering it. What is amazing is to understand that Greenland has a population of 56,000 residents concentrated along the southwestern coast.

A totally different perspective of the Northern Hemisphere.

The North Pole map highlights the shipping routes opening as the Arctic Sea ice shrinks. From a national defense perspective, new shipping lanes provide easy access for Russian and Chinese naval ships to the North Atlantic, potentially threatening European and North American countries.

The strategic location of Greenland was recognized in the early days of World War II. After German troops overran Denmark, the owner of Greenland, the Nazis established weather stations to gather information for its planned attack on the U.K. Fearing for the safety of American ships plying the Atlantic to bring military supplies and goods to the U.K., President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the establishment of U.S. weather stations and a military presence on Greenland. The troops maintained an airfield and fuel supplies for American planes shuttling across the Atlantic and a port for naval ships protecting merchant vessels on their way to the U.K. Roosevelt also ordered the military to destroy the Nazi’s weather stations, which they did.

Opening Arctic Sea shipping lanes requires nations to maintain icebreakers to keep them ice-free. Icebreakers are also available to free any ship becoming icebound. Therefore, the capabilities of icebreakers are essential. Icebreakers are classified based on the thickness of the ice they can handle. Polar-class ships are built for the thickest ice, while conventional icebreakers are limited in the ice thickness they can break up.

Icebreakers are designed to push their bows onto the ice and break it with the ship’s weight. Therefore, power and strength govern their design. Typically, oceangoing ships are designed and built for speed and fuel efficiency. Icebreakers are built with reinforced hulls to deal with the strength of ice flows. Those reinforced hulls add significant weight to the ships. The additional weight and strength to crack the ice means icebreaker engines must sacrifice fuel economy for power.

A Wall Street Journal analysis of the global icebreaker fleet, based on The Arctic Institute and Arctic Marine Solutions data, shows the world’s largest fleet is Russian. It owns 32 icebreakers, six of which are Polar-class. Russia has three icebreakers under construction. Canada has the second largest fleet – five vessels with three under construction, one Polar-class, and two conventional icebreakers. The U.S. icebreaker fleet ranks sixth with two ships, including a Polar-class ship. It has a traditional icebreaker under construction. Sweden, China, and Finland have fleets larger than the U.S.

The challenge for the U.S. and other Western nations is having the shipbuilding capacity to construct the number of icebreakers they need to keep shipping lanes open. Last year, China built 75% of the delivered global merchant ships. The U.S. lacks the shipyard capacity to build large ships such as icebreakers. This lack of shipyard capacity also impacts the building of navy and merchant ships.

Polar Star, the U.S.’s largest icebreaker, was commissioned in 1976 and is nearly 20 years beyond its designed service life. A sister ship, Polar Sea, was commissioned in 1977 but has been out of service since 2010.

Polar Star has six 3,000-horsepower (hp) diesel engines and three 25,000-hp gas turbine engines. It can travel at 18 knots and 3 knots in 6-foot thick ice.

Healy, the nation’s second icebreaker, was commissioned in 1999 but has less horsepower than Polar Star. Although larger than the Polar Star, it is classified as a medium icebreaker. It was designed and operates as a scientific research vessel. Two 15,000-hp diesel-electric engines power it. While it can travel at 17 knots, it is limited to 3 knots in 4.5-foot thick ice. Therefore, it often requires assistance when operating in thicker ice regions.

The Trump administration has recognized the importance of strengthening its Atlantic defenses, which is behind the push for some deal involving securing control over Greenland. Recognizing the importance of the Arctic region from a defense perspective means adding to the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard’s capabilities for operating in the ice-prone regions.

The U.S. government commenced an icebreaker fleet upgrade plan in 2019. It contracted the first of three planned icebreakers but is not expected to be delivered before 2030. The Congressional Budget Office projects that the program will cost $5.1 billion, 60% more than original projections. Long delivery times and inflated costs plague almost all U.S. military and commercial shipbuilding projects.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Bollinger Shipyards had to invest $20 million to expand and upgrade its yard to take over construction of the Coast Guard’s new Polar icebreaker from VT Halter Marine, a company it had bought. Halter had lost $250 million on the project before starting construction. The losses likely resulted from the lack of institutional knowledge about constructing a Polar-class icebreaker. More than 40 years after building our last icebreaker, we are now building a new one. The shipyards that built Polar Star and Healy have shut down. The skills required to design and build these ships have been lost. Realistically, our large ship construction skill set has shrunk and must be rebuilt to protect our defense capability. These skills will be necessary for the revival of our commercial shipbuilding industry.

Globally, between 2009 and 2022, the number of “large” active shipyards fell from 320 to 131, with reports that the number declined further in 2023. In the U.S., a database maintained by www.shipbuildinghistory.com lists five shipyards building large U.S. naval vessels and submarines, 15 active shipyards that build large vessels, and 60 formerly active shipyards. Included in the 15 yards capable of constructing large vessels are Bollinger Shipyards and VT Halter. Based on our knowledge of most of the 15 shipyards, we believe few can build the large ships our merchant fleet needs.

The Shipbuilding and Harbor Infrastructure for Prosperity and Security for America Act of 2024 (SHIPS Act) is designed to revitalize the United States as a maritime nation by establishing national oversight and consistent federal funding for the U.S. maritime industry. Key provisions of the SHIPS Act include:

1. Establish a White House-level Maritime Security Advisor position.

2. Establish a Maritime Security Trust Fund to support U.S. maritime transportation.

3. Directs the Secretaries of Transportation, Defense, and Homeland Security to acquire and maintain sufficient commercial and military sealift capability to meet U.S. national defense and economic security objectives.

4. Establishes the Strategic Commercial Fleet Program to establish a fleet of 250 privately owned, U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged, U.S.-crewed that operates in international trade.

5. Establishes a shipbuilding financial incentive program that allows the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) to aid in the construction of U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged vessels and to make investments in U.S. shipyards and facilities that produce critical components for shipyards.

6. Provide incentives for recruiting and retaining mariners and shipyard workers.

7. Provides for the Maritime Security Trust Fund to be funded by duties, fees, penalties, taxes, and tariffs collected by Customs and Border Protection.

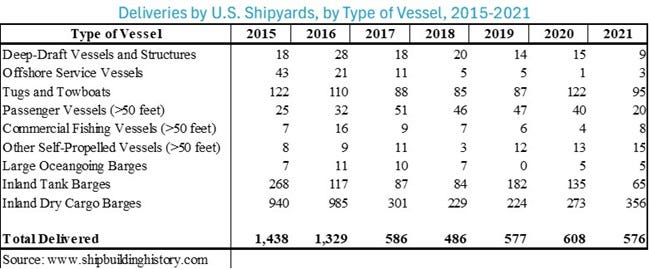

While there are claims in the media that the U.S. shipbuilding industry is healthy and robust, the following table shows it is not competitive in the global shipping industry. The U.S. has a number of shipyards and ship repair and maintenance facilities, but it does not have yards that can build many large oceangoing ships.

U.S. shipyards are good at building small vessels but not large, deep-draft ones.

While the data ends in 2021, the record is clear that only a fraction of total vessels delivered from U.S. shipyards are deep-draft vessels. Between 2015 and 2021, an economic period of low inflation and low interest rates, the total number of vessels built in domestic shipyards fell by more than half.

The SHIPS Act has not received much publicity. It is clear from the above data that the U.S. shipbuilding and maritime industry needs government support, such as the provisions of the proposed legislation. The most recent action of the Trump administration is to impose substantial port fees on Chinese vessels to encourage U.S. importers to use U.S.-flag vessels. These fees would be part of the Maritime Security Trust Fund funding. There is also a provision in the SHIPS Act that requires the use of U.S. flag vessels for a portion of the goods imported into this nation.

However, as we follow the maritime industry, other countries active in shipbuilding and maritime activities are taking steps to bolster their domestic industries. China is actively expanding its shipbuilding capacity, which has constructed nearly half of all the ships delivered in the past three years and three-quarters of those built last year. Chinese shipyards that went bankrupt or closed during the pandemic are reopening or have been acquired by active shipbuilders.

South Korea is investing 260 billion won ($181 million) in its shipbuilding industry this year, up 40% from last year. The spending is to ensure its shipbuilding sector remains competitive. The industry sees the need for local shipowners to build 100 ships a year to meet the nation’s carbon emissions reduction goals.

In December, Davie Shipbuilding announced partnerships in Canada to help it transform a shipyard in Quebec into North America’s largest and most versatile shipbuilding center. The expansion is backed by substantial funds from the provincial government. The upgraded facility is crucial for delivering seven Polar-class icebreakers and two hybrid ferries under Canada’s National Shipbuilding Strategy. Davie also wants to purchase a U.S. shipyard to complement its recent Finland shipyard acquisition and position the company for icebreaker orders in both countries.

Davie was named the third party to Canada’s National Shipbuilding Strategy in 2023. It joined Irving Shipbuilding in Nova Scotia and Seaspan Shipyards in Vancouver in the program. The strategy focuses on two vessel categories – non-combatant vessels (ice breakers, offshore science vessels, and support ships) and combatant vessels (frigates and Arctic offshore patrol ships).

India is the latest government to announce a commitment to expanding and upgrading its maritime industries. On February 1, the Indian government announced the establishment of a $2.9 billion maritime development fund for long-term financing of the country’s shipbuilding and repair industry. Recently, Maersk, the Danish cargo giant, announced plans to collaborate with Cochin Shipyard Limited to explore ship repair, maintenance, and shipbuilding opportunities in India. The collaboration capitalizes on the Vision 2047 maritime objectives and recent 2025-26 budget announcements to position India among the top five global maritime hubs.

The sudden focus on expanding and upgrading shipbuilding businesses in countries around the globe reflects the need for more ships. They will be needed to facilitate the growth in global trade. More ships than the industry can build will be required to move the critical minerals to enable the clean energy transition. Geopolitical tensions are forcing the creation of new and longer ship routes, which consume existing shipping capacity. Then, there is the need for ships with cleaner power to meet the International Maritime Organization’s push for carbonless fuels. Finally, there is the need to refresh the global shipping fleet, as inflation, COVID-19, and uncertainty about clean power fuel availability have slowed replacing existing shipping capacity.

The shipping industry is responsible for moving 80% of global trade. However, because ships spend most of their lives traversing oceans, the maritime industry has very low visibility, yet is critical to the functioning of the global economy. The Wall Street Journal article on icebreakers highlights the global shipbuilding challenge. We are waiting for the response.