Energy Musings - December 23, 2024

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays to our readers. Part 3 of our series adds to the drama between Sweden and Germany over cheap power and looks at Europe's economic problems.

Winter, Renewables, And Europe’s Economy – Part 3

In Parts 1 and 2 of this series, we discussed Europe’s problems, especially those of Germany, Norway, and Sweden, during the recent wind lull. Idled wind turbines forced Germany to import cheap power from Norway and Sweden. Their cheap electricity enabled Germany to minimize the price spike. However, losing their surplus power caused electricity prices in Norway and Sweden’s populous southern regions to soar, angering their citizens and upsetting politicians.

The resulting backlash sparked politicians to demand changes to their interconnector cable arrangements that enabled the surplus power to be exported. Politicians threatened to renegotiate the interconnector contracts and even tear out two cables connecting Norway and Denmark. The spike has injected regional electricity prices into the upcoming Norwegian election campaign. Sweden’s energy minister even lectured Germany for its dumb energy policies – shutting down its nuclear power plants and gaming the continent’s electricity system to suck Scandinavia’s cheap power.

In this part, we first catch up on the latest Swedish news about the German interconnector issue. Then we address how Europe’s green energy policies are crippling its economies - Germany being Exhibit 1.

Sweden Challenges Germany Over Electricity

“I’m furious with the Germans,” said Sweden Energy Minister Ebba Bush. She pointed out that their decision to shut down their nuclear power plants has produced “serious consequences” for everyone else’s electricity grids. She meant Norway and Sweden, which have substantial cheap hydropower. The pain comes from the European Union’s Flow-Based Market Coupling, a market system designed to optimize cross-border electricity flows by prioritizing demand across the European power grid rather than focusing on specific national needs.

The system was introduced in Sweden in October, but the government had the opportunity to pause it and its disruption of the nation’s economy. High electricity prices hurt consumers and industry. The latter were critical of the system before it was adopted. They warned of electricity price spikes caused by Sweden’s surplus power being exported to Europe. That reality occurred a week ago and could happen again during the winter. Wind lulls and a lack of solar power put pressure on grids, forcing them to rely increasingly on hydrocarbon energy sources to generate electricity.

Soon after her comments, Energy Minister Bush told reporters that Sweden was prepared to approve a power cable from southern Sweden to Germany if it reorganized its electricity market to stop drawing so much low-cost power from overseas. Bush was referencing the proposed 700-megawatt Hansa Power Bridge. The project would remain postponed “until Germany gets its system in order.”

What changes does Germany have to do to win the support of Sweden and the new cable? Bush suggested that Germany should split its national electricity market into bidding areas that would increase the efficiency of the grid and lower prices. The problem with Germany’s grid is that with a significant share of renewable energy, it suffers from periods of overproduction and huge power deficits. The deficits force Germany to tap the cheap surplus power of Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Sweden.

Bush highlighted that the wind lull and Germany’s power pull caused southern Sweden’s electricity prices to jump from “minus prices” to around €1 ($1.04) per kilowatt-hour during the recent wind lull. She said, “That makes for a very difficult business case.”

Norway and Sweden are not the only countries criticizing the structure of the European Union’s electricity system. Last summer, Greece experienced inexplicably high electricity prices. Greek Prime Minister Kryiakos Mitsotakis referred to the EU’s electricity system as a “black box” that must be better understood. He suggested that there needed to be a regulator who was responsible for examining the issues and had the power to intervene.

These issues are becoming more important because the EU’s energy regulator reported that electricity network costs could double by 2050, “endangering the overall affordability of electricity bills.” This is not good news for European residents and, without restructuring its grid, the citizens of Scandinavia. They will face higher electricity bills, and their jobs could be at risk.

Europe’s Economic Woes From Costly Energy

Europe’s economy has struggled for most of this century, especially in recent years, as growth has slowed and energy costs have skyrocketed. In 2007, the Gross Domestic Product of Europe was $14,728 billion compared to the $14,474 billion of the United States. Last year, the U.S. GDP grew by 89%, while the European Union’s GDP only increased by 25%. Over this period, the gap between the EU and the U.S. shrank from 70% to 50% on a per capita GDP basis.

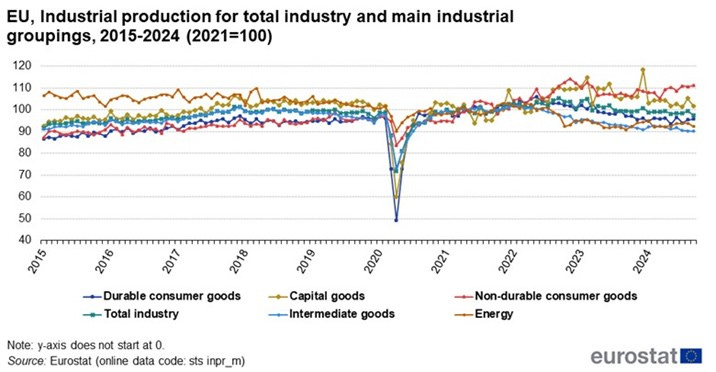

The reason for the lack of GDP growth is weak industrial production. The following chart based on Eurostat data for 2015-2024 shows there has been little progress in almost every category of goods. The only category noticeably higher than in 2015 is non-durable consumer goods. These are the things that families and businesses need for everyday living and operating.

Europe’s economy has shown little growth for a decade.

Eurostat commented on the trends in the chart. It noted that total industrial production increased slowly between 2015 and 2018, but the pace stagnated during 2018 and 2019. Activity in 2020 was upset by the Covid-19 crisis, but industrial output began to recover later in the year and continued in 2021. The industrial production trend changed after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022. Between August 2022 and September 2024, industrial production fell by more than 6%, driven by massive declines in durable consumer goods (-7.0%) and intermediate goods (-8.5%). However, non-durable consumer goods production increased by almost 3% during 2023-2024, again what people need every day.

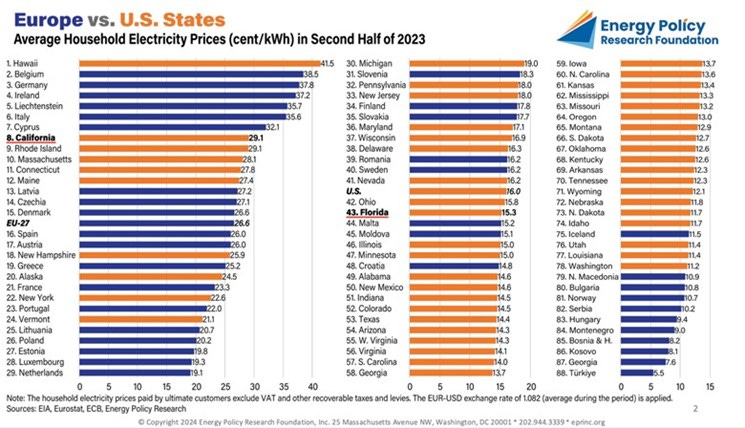

A major problem for Europe, and Germany, in particular, has been the price of energy and electricity. Between December 2007 and June 2024, the average EU price per kilowatt-hour of electricity went from €0.154 ($0.16) to €0.289 ($0.30), an 88% increase. Over the same period, the average U.S. residential price increased from 12 to 18 cents per kilowatt-hour, a 50% hike. Germany’s electricity is much more expensive than the EU average. For this period, Germany’s household electricity price climbed from €0.2025 ($0.21) to €0.3951 ($0.41), a 95% increase or nearly three times the U.S. increase.

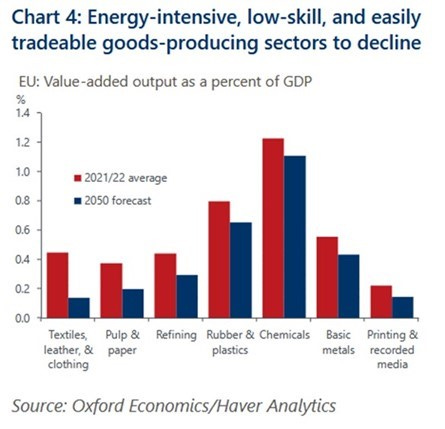

A study by Oxford Economics ‒ “The future of industrial activity in Europe” ‒ stated that the continent is not experiencing deindustrialization as popularly thought. Instead, it faces structural and cyclical headwinds. Oxford calls the environment an industrial recession.

The reason why it chose recession is because only certain industries are in decline. The declining industries have common traits: they produce lower value-added goods that can be easily transported and traded, need low-skilled labor, and are energy-intensive. The industries Oxford identified include textiles, basic metals, and, in some cases, chemicals.

European industries are shrinking.

Oxford believes that Europe will do well if it emphasizes industries that rely on specialized, high-knowledge, high-skilled workers. That means mechanical engineering, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and electrical machinery businesses. The Oxford researchers see these industries expanding and offsetting the declines of other industries.

A significant European industry challenged by economic issues is the automotive sector. However, the study said structural issues related to demographics, foreign competition, and the electric vehicle (EV) transition are impacting its future. We were surprised that Oxford believes this sector’s “output growth is likely to remain robust.” We question this conclusion based on the planned shutdown of three Volkswagen manufacturing plants for the first time in the company’s history and output cutbacks by other auto manufacturers. [Volkswagen and their unions agreed to a deal to avoid shutting down the plants or wage cuts in the near-term. There is more to learn about the deal. It sounds like kicking the can down the road, not solving Volkswagen’s problems.] Reportedly the deal involves future job cuts and Their conclusion appears to be based on the recent increase in auto exports, which assumes expensive German autos will remain competitive globally. Porsche, which is taking up to a $21 billion impairment charge for its Volkswagen investment, announced that it might be forced to shut plants, putting 8,000 workers at risk.

Oxford does get right that the automotive sector, with the shift to EVs, will not be the job creator it was previously. Moreover, unemployed automobile workers will leave high-skilled, high-paid jobs, negatively impacting local economies.

The Oxford study concluded that manufacturing’s share of the continent’s economy can grow but not employment. Breaking that historical linkage between manufacturing and employment is due to the shifting mix of industries growing or shrinking. The low-valued industries in decline have high labor input. Therefore, as their output declines and they shrink, a disproportionately higher number of jobs will be lost. Conversely, growing industries will be hiring, although those expected to grow do not employ as many workers relative to their output. This has been a problem for Germany for decades. While Germany’s manufacturing share of its total economy is about the same as in the early 1990s, it employs a quarter of the number of employees.

Germany’s manufacturing industries are not adding jobs.

The high cost of energy is a significant problem for energy-intensive industries such as metals, machinery manufacturing, and chemicals. Companies within these industries have announced plans to manage their output based on the cost of electricity. Their challenge was summed up in a report to EU leaders this fall by Mario Draghi, the former European Central Bank chief and EU economic guru. He used the high electricity bills to make his case for a massive overhaul of Europe’s way it conducts business.

His idea of an overhaul was to accelerate the shift to green energy. His message supported EU officials who see green energy as the continent’s future. They say cheaper renewable energy is coming but acknowledge that it will take years to make the necessary structural changes. This point is central to every consultant’s report to the government about their green energy plans. The message: financial pain from higher energy bills in the near term will be forgotten when cheaper renewable energy arrives.

For Germany and Europe, the problem is the time is short. China’s industrial strategy is to compete in the green energy space and in many basic manufacturing sectors, where its massive capacity, cheap labor, and control over critical minerals enable it to eat into Europe’s market share at home and abroad. At the same time, China sees that Europe’s efforts to compete in EVs and artificial intelligence will strain local grids, impoverishing Europe’s citizens while they await the arrival of the nirvana of cheap renewable power.

Maybe the citizens understand their future if they follow the EU’s plan better than the politicians. We were surprised that the EU officials aren’t paying more heed to Draghi’s warning. “For the first time since the Cold War, we must genuinely fear for our self-preservation.”

Our last chart shows the stark reality that European countries and U.S. states, which have embraced renewables, are at a competitive disadvantage versus those that have not. The prices will be higher in 2024. Ranking at the top of this chart is not an honor but should be taken as a warning.

European countries embracing renewables head the expensive power list.

The 2025 economic forecasts for Europe and its leading economies show more of the same – slow growth and painful futures for citizens and businesses. It should not be a surprise that the political elites are being tossed out by the voters when given the chance. Germany is likely the next to go through that exercise next February. The problem is that new government leadership that understands the damage done to their economies by the reckless energy policies of prior leaders cannot work magic and correct the mistakes as quickly as the public wants. Europe will be in turmoil for years to come.