Energy Musings - December 16, 2024

Europe's wind lull and colder weather pushed electricity prices in Germany to record highs. It also pushed Norwegian electricity prices up as it sent surplus power to Europe. That supply may be cut.

Winter, Renewables, And Europe’s Economy – Part 1

“The German economy is struggling not just with persistent cyclical headwinds but also with structural problems,” said Bundesbank president Joachim Nagel. He was addressing the bank’s latest economic forecast for the German economy, which predicts 2025 growth of barely 0.1%. The central bank’s latest update is only one-tenth of its 1% 2025 GDP growth forecast in June.

Nagel’s reference to Germany’s “structural problems” highlighted its weak productivity growth and the nation’s struggles in the manufacturing industry. In reality, he might have said that Germany’s problems are self-inflicted. Politicians have embraced stupid climate change policies, which have driven Germany’s power grid to depend on unreliable renewable energy, with soaring electricity prices the outcome.

Nagel’s quote comes from a Financial Times article about the Bundesbank’s December report including the revised economic forecast. The article also discussed the bank’s warning that if President Donald Trump’s tariffs were implemented ‒ 10% on European goods and 60% on Chinese exports – the German economy would fall into a recession. The bank estimates Trump’s tariffs would cost Germany’s economy 0.6% next year, sending its 2025 GDP growth projection to a negative 0.5%.

Germany’s electricity problems are top-of-the-mind because a second winter wind lull has just hit the European continent, forcing countries to scramble for available power from their surplus-rich Scandinavian neighbors. The surplus power is shipped through a network of intercontinental submarine cables. Unfortunately, these interconnector cables are becoming a problem.

Here is data from Wind Europe showing the problem Germany’s grid faced from the wind lull. On Monday, December 9, Germany’s wind turbines produced 742 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of power, 49% of its needs. Tuesday, wind’s output dropped by nearly 70% to 234 GWh, 16%. Wednesday was worse. Germany’s wind turbines generated 56 GWh, below 8% of its needs. Thursday was even worse as Germany generated only 36 GWh, less than 6% of needed power. Friday’s output improved as Germany generated 152 GWh, 11% of the nation’s need. Wind Europe only lists the top 10 countries by wind’s share of the country’s power needs. It also lists the top 10 countries by national wind output. Therefore, the 8% and 6% figures cited above reflect the tenth country’s wind share, and since Germany was not on that list, its share fell below the last country’s percentage.

The insatiable power demands of countries like Germany and the UK that have gone all-in on renewable electricity are soaking up Norway’s and the other Scandinavian countries’ surplus power. This has sent Norwegian electricity prices sky-high, angering its residents accustomed to low prices because of the country’s 1,000 hydropower-generating plants. According to media reports, the wind lull pushed electricity prices in southern Norway to $1.18 per kilowatt-hour last Thursday afternoon. That is the highest the country’s electricity prices have been since 2009, almost 20 times the prices of the prior week.

Wind lulls in winter require fossil fuel backup power.

The chart shows the wind and solar power generated in Germany for 2024 through mid-December. Note the white areas in the chart – particularly in January, November, and December (end of the chart). Those are the times when the wind stopped blowing, and there was little or no solar power. The grid called on gas and oil-fired generators and imported power to compensate for the shortfall. This was costly for German ratepayers, and the residents of the countries supplying the imported power.

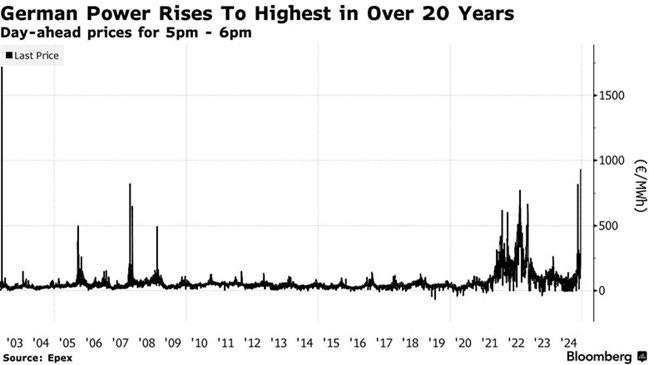

The domino of higher electricity prices began on Wednesday when the wind lull commenced. In Germany, fossil fuel-fired power plants ramped up to supply electricity. Power prices soared over €1,000 ($1,050) per megawatt-hour and remained elevated through Thursday. The power price spike stands out in the following chart. What we found interesting was how much higher power prices were following the 2022 energy crisis compared to all the history before. The higher power prices reflect the grid disruption and subsequent price response from the increased penetration of renewable energy.

German power prices soar, harming its citizens and economy.

Norwegian electricity prices, like those of Germany, exploded. In Norway’s case, it was due to the sucking up of the country’s surplus power. The price explosion was characterized by the country’s energy minister Terje Aasland as “an absolutely shit situation.” His center-left Labour Party government says it will campaign on turning off the interconnectors to Denmark when they come up for renewal in 2026. The Labour Party is being outdone by its junior coalition partner, the Centre Party, which wants to end the Danish interconnector agreement and also renegotiate the interconnector agreements with the UK and Germany.

We were surprised to learn of Norway’s large number of regional interconnections. According to Ingvild Kjerkol, a lawmaker with the Labor Party, Norway has 17 interconnections. It is connected to neighboring Sweden and via subsea cables to Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. This summer, Norway turned down a request from the UK to build a new interconnector. It was concerned about the impact of the additional interconnector on Norway’s power prices.

The two Danish interconnectors are reaching the end of their technical lives in 2026 and 2027. “But when these two cables need to be phased out anyway, then we don’t believe in replacing them,” said Kjerkol.

Norway is not about to stop sending surplus power to the continent and the UK, but the cost of that power is going up. Sometimes, Norway uses the interconnectors to import electricity from the continent because of problems with its hydropower supplies. The interconnections are considered great insurance for countries with high renewable generation shares, but the system has always been at risk of a continent-wide wind lull. In that case, there will be little or no surplus power to shift around. Surprisingly, that is not the rare condition renewable power promoters want you to believe. There is ample evidence in the history of extended continent-wide wind lulls.

Currently, the Norwegian government pays 90% of the cost of electricity above a specific price, cushioning Norwegians against having to pay those ultrahigh electricity prices. The right-wing Progress Party, which currently leads in the Norwegian polls, wants the government to pay for all the electricity above a lower price. It argues that the government makes billions of kroner from the high electricity prices through its hydropower generation. The Progress Party also wants to scrap the Danish interconnector and reform the UK and German agreements.

Scandinavian countries, however, have internal electricity pricing problems. Most hydropower generation is done in their northern regions, but their population centers are in the south. The challenges in connecting the generation to the consumption lead to low electricity prices up north and higher prices in the southern cities.

These interconnectors’ future has become a meaningful political issue, and their future will be a topic debated during the upcoming political campaign leading up to next September’s election. In Norway, another problem is that its natural gas has become a critical supply source for European countries forced to curtail their use of cheap Russian gas. This reshaping of the European electricity market will have long-lasting impacts – witness the Bundesbank’s GDP forecast. Part 2 will explore this impact.