Energy Musings - August 9, 2024

The stock market crash was likely caused by the BOJ hiking interest rates and ending the Japanese yen carry trade. Still, recession fears abound. Revised EIA gasoline data added concerns.

Recession Talk and Energy Demand; What’s Up?

Last Friday’s jobs report produced a disappointing number that spooked investors, strategists, and liberal economists. OMG! The nation only created 114,000 new jobs; the second lowest monthly jobs increase since December 2020. Moreover, the estimated number of jobs created during the prior two months was revised lower by 29,000. Additionally, 430,000 people entered or re-entered the labor force, swelling it and pushing the unemployment rate up by two-tenths of a percent to 4.3%. That was the highest unemployment rate since October 2021.

Not only was the labor market data disappointing, but the sharp rise in the unemployment rate tripped the Sahm rule. The rule, named for economist Claudia Sahm who defined it, states that a recession is underway when the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate rises half a percentage point above its low from the previous 12 months. The July unemployment rate is nearly a full percentage point above its January 2023 low of 3.4%.

Investors reacted to their disappointing data by selling stocks. They shifted the money into the bond market causing interest rates to dip below 4%. Investors looked back at the Wednesday press conference by Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell where he teed up the possibility of a September interest rate cut. Something investors have been clamoring for.

As Friday’s disastrous stock market drop unfolded, economists and investors questioned whether the Fed had made a mistake by not cutting rates at its recent meeting. This stoked a narrative that the Fed was behind the curve, which would limit government efforts to hold off a recession. Therefore, an immediate Fed cut should be enacted and be greater than the typical quarter-point move.

Never buy stocks on Friday because who knows what might happen on Saturday and Sunday, given the hours investors have to stew in their worries. You could also have other bad news over the weekend, and there is plenty of time for articles pushing a negative sentiment.

Before the market opened on Monday, stock futures prices signaled a 1,000-point drop for the Dow Jones index. And that is exactly what happened. While the magnitude of the decline yo-yoed during the day, the Dow Jones ended slightly over 1,000 points lower. Investor panic drove talk of a Federal Reserve emergency meeting to correct their mistake of not cutting the interest rate. Crying investors clamored for the pacifier of lower interest rates.

As Monday’s disaster unfolded, recession talk dominated the explanations for what drove the market lower. Slowly, however, another narrative emerged. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) was the cause of the drop. How could that be? It was the “carry trade,” an investment trade in which money was borrowed cheaply in Japanese yen, immediately converted into U.S. dollars, and invested in high-tech Nasdaq stocks, which were soaring.

The BOJ spoiled that trading party. On July 31, the bank raised interest rates from 0.1% to 0.25%, the largest rate hike since 2007. In addition, the bank indicated it would begin scaling back its purchases of bonds. The new plan calls for reducing the buying by ¥400 ($2.725) billion each quarter through March 2026. Currently, the bank is buying ¥6 trillion ($41 billion) a month.

The impact of the interest rate hike and the signal of a reduction in bond buying (injecting money into the Japanese economy) was reflected in the value of the yen-to-U.S. dollar relationship. On the rate hike news, the yen immediately rose to about 150 to the U.S. dollar from about 162 earlier in July. By Monday morning, the yen rose further to around 143. Using “rose” is because the yen’s value relative to the dollar increased.

The estimated $4 trillion carry trade suddenly became less profitable. The hedge funds engaged in this carry trade were suddenly hit by a classic “margin call.” That is when the cost of the money borrowed to buy an asset rises to the point where the asset must be sold to repay the loan. This may save some profit from the trade, but it protects against larger losses. Between early July and last Monday, the yen’s value appreciated nearly 13%. That means hedge funds needed to earn 13% on their investments in addition to any interest charges involved in the carry trade. The increase in the carry trade’s cost explains why hedge funds dumped their stocks to repay their yen loans.

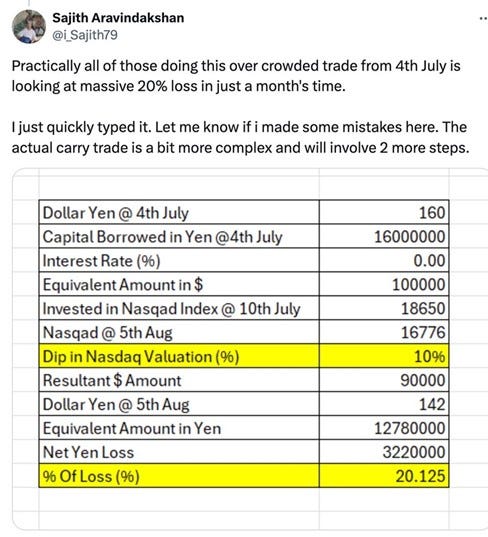

Adam Tooze wrote in his newsletter Chartbook about the yen carry trade. He utilized examples from others reporting on and analyzing the impact of the BOJ’s interest rate hike. Here is an analysis of how the carry trade worked and quickly became a devastating financial loss.

The sharp rise in the yen value turned profitable carry trades into money losers.

As the table shows a 10% decline in the value of the Nasdaq over the prior month was turned into a 20% loss by the collapse of the yen’s value due to the BOJ rate hike. Hedge funds are rapid traders, meaning they respond rapidly to conditions that differ from their assumptions when they instigate the trade. An almost immediate 21% loss needed to be cut off before the loss grew larger.

The BOJ began keeping interest rates low and engaged in an aggressive bond-buying program to help prop up the country’s economy for over a decade. It started in response to efforts to assist Japan’s recovery from the 2008 Great Financial Crash.

That monetary condition encouraged hedge funds to capitalize on the carry trade. When interest rates were low, the hedge funds made lots of money. They borrowed cheaply and invested in the high-flying tech stocks in the U.S. market. What could go wrong? Higher Japanese interest rates.

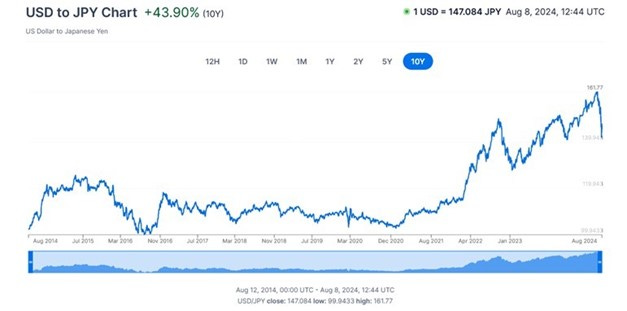

The following chart of the yen-dollar relationship since 2014 shows that until 2020, while the exchange rate fluctuated the change was almost non-existent. However, after the dollar strengthened (the yen value rose), Japan’s Finance Ministry became concerned with what was happening to its economy because of the weakening of the yen’s value. The BOJ began a major yen-buying effort in October 2022 to prop up the currency. This was the first currency intervention by the BOJ since 1998. Since that October intervention, the BOJ has made other moves to prop up the yen’s value.

The chart shows the yen going from about 100 at the end of 2020 to its recent high of 162. That explains why hedge funds borrowing in yen and investing in the tech-heavy Nasdaq made a ton of money. At the end of 2020, the Nasdaq index was trading about 7,500. Its recent peak was 18,400, a nearly 150% increase. By utilizing borrowed yen which cost almost nothing, hedge funds were able to boost their returns even more.

Since 2020, the rise in the Japanese yen’s value highlighted how hedge funds made money in their carry trade.

The Japanese carry trade is another example of the changed monetary world. Hedge funds engaged in the carry trade suffered as elevated Japanese interest rates dramatically changed the market conditions that had made the carry trade so profitable. It is like the renewable energy developers who tapped cheap money to build their projects. When interest rates increased in 2022 and 2023 in response to soaring U.S. and global inflation from pandemic-related government spending, those capital-intensive renewable energy projects suddenly became loss-generators. At one point, 60% of the approved offshore wind capacity additions were canceled. Developers exited previously negotiated electricity sale agreements paying nearly $100 million in penalties to prevent building projects that would lose money for decades.

As we struggle to understand the implications for economic sectors that benefitted from the cheap money era, the signals about the health of the current economy are mixed, making future investment mistakes difficult to uncover. A factor making the confusion about the economy more difficult to sort out is the latest revised oil demand data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

The EIA was established following the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo. While other government agencies had collected energy data, the reporting was not as timely nor as granular as the energy industry and the market needed. No other government agency engaged in energy forecasting, which the EIA was charged with conducting. Politicians recognized data timeliness, accuracy, and future assessments were crucial for developing sound energy policies.

An example of a data timeliness failure is the gasoline market during the 1970s energy crises. Using old data, the government set controls that ignored regional growth trends. Thus, regions with rapid population growth had to grapple with gasoline supply shortages. It forced gasoline stations to ration the fuel a vehicle owner could purchase. The famous odd-even rationing system based on the last digit of your license plate became a popular and easy way to regulate fuel purchases. On the other hand, regions with falling populations found their gasoline stations swimming in fuel. That meant no rationing or waiting in lines for fuel.

The EIA’s recent vehicle fuel consumption data revision reportedly has energy professionals scratching their heads. Media stories reported that energy traders who rely on the EIA’s weekly data to guide their buying and selling of supplies are upset.

The EIA periodically matches its weekly supply estimates with its monthly data. The match is done with a two-month lag. This time, the revision created a markedly different narrative about the health of U.S. gasoline and oil demand that existed based on the weekly data.

The May weekly gasoline numbers showed demand weaker than in the past. That supported traders’ belief that electric and more efficient gasoline-powered vehicles are eroding demand. However, the monthly data created the opposite narrative – demand was up. Instead of summer starting with weak gasoline purchases, it began with a post-pandemic high.

Why is the data revision of such concern? Traders and analysts are beginning to question their continued reliance on the accuracy of the EIA’s data. That could spill over into Washington’s energy policy decisions, the amount of oil produced by OPEC+, and how much oil and gasoline buyers should import.

Historically, the monthly weekly data revisions find differences of 100,000 to 200.000 barrels per day (bpd), marginal adjustments in a U.S. oil market consuming 20 million bpd.

This time, instead of May’s weekly data showing gasoline use at just over 9 million bpd compared to last year’s 9.1 million, the monthly data reported consumption was nearly 400,000 bpd higher. That topped 2019 use despite higher gasoline pump prices.

Along with the gasoline revision, other petroleum product demand estimates were adjusted. It resulted in May’s U.S. oil demand hitting a seasonal record of 20.8 million bpd. April’s consumption was also revised by 400,000 bpd above the weekly estimates.

The explanation for the dramatic data revision was that the EIA’s weekly figures in May overestimated gasoline output and undercounted exports.

The frustration of energy traders was summed up in a quote from Tom Kloza, head of energy analysis at Oil Price Information Service (OPIS). “It makes you wonder why anyone is paying attention to the weekly numbers,” he told EnergyNow.com. OPIS publishes its gasoline demand estimates based on data from about a quarter of the 150,000 gasoline stations in the nation. The OPIS data has consistently shown deteriorating year-on-year demand, consistent with the EIA’s original May weekly estimates.

GasBuddy.com, another fuel data and price tracking service, finds its data aligning more closely with the EIA’s May weekly estimates. GasBuddy had May gasoline demand at 8.87 million bpd, close to the EIA’s roughly 9 million weekly estimates.

Traders expressed frustration with the EIA data and whether they should continue to rely on it. Many subscribe to numerous private data feeds in addition to the EIA data. Some traders have even chartered helicopters to fly over storage tanks at oil trading hubs enabling them to estimate how much oil has moved in and out of them.

Rattling the traders and policymakers is that the EIA is the only government agency issuing such granular data and updates on consumption. They still believe it is an unbiased view of the oil market at a time when OPEC and the International Energy Agency (IEA) have widely different thoughts on the direction of the global oil market.

GasBuddy analyst Patrick De Haan, commenting on the data revision, stated, “It’s a trend that’s a little concerning to me.” De Haan summed up traders’ concerns. “The EIA has been the bedrock for analysts, but skeptics may be gaining more validity to arguments that the EIA numbers aren’t jiving to the real world,” he said.

Bad market data creates a conundrum for energy traders, policymakers, investors, and energy company planners. Should they believe and plan using their market intelligence, or continue relying on the EIA data? The data conflict will be resolved at some point, but that prospect is of little comfort to current energy market participants. In the meantime, the data confusion does not answer whether the U.S. and possibly the world are in or heading into a recession. Tread carefully and watch all the data coming from businesses and governments.

Thanks, Kit.