Energy Musings - August 29, 2024

Settled science says we are destined to live in a hotter and dryer climate with negative outcomes for the world's population. More CO2 is greening the planet and slowing the increase in emissions.

Settled Science Isn’t So Settled After All

The science is settled. It says global warming, or boiling if you happen to be the Secretary-General of the United Nations, leads to greater desertification of the planet. More dusty and dry land is our future. The great agricultural regions feeding the world will be forced to move north to cooler locals if crops are to grow. It is not only that the heat would dry out the land but there would be reduced rainfall. What would be the result? A world with food shortages and people starving to death would be our fate.

What’s the cause of this disaster? It is hydrocarbons. Seizing on the settled science, climate activists demand we immediately end burning hydrocarbons.

Wait a minute. We are now learning that science isn’t so settled. The world is not experiencing massive desertification. Instead, the deserts and drylands are greening. How could that be happening?

Greening of the planet is driven by increased carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), which is the exact opposite of the “settled science” of global warming. It must be time to find a new science problem because the old one isn’t working.

A recent article in Yale Environmental 360 argues that greening deserts and drylands create water problems. This will disrupt the deserts and drylands because new plants will crowd out the native ones. In other words, we are destroying the deserts by greening them. That must be a bad outcome. There is no room for plant life to adapt to increased CO2.

The Landscape

Deserts represent about 40% of the world’s land mass. According to the International Union For Conservation of Nature, deserts provide homes to more than a third of the world’s population. They are also among the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world. What is causing the deserts to change is the large increase in CO2. And we thought green was good.

The article points out, the 50% increase in CO2 emissions since the start of the industrial era is not only causing climate change but it is boosting photosynthesis in plants. The latter happens because CO2 allows plants to use scarce water resources more efficiently. The CO2-rich air fertilizes plants and causes vegetation growth even in arid locations.

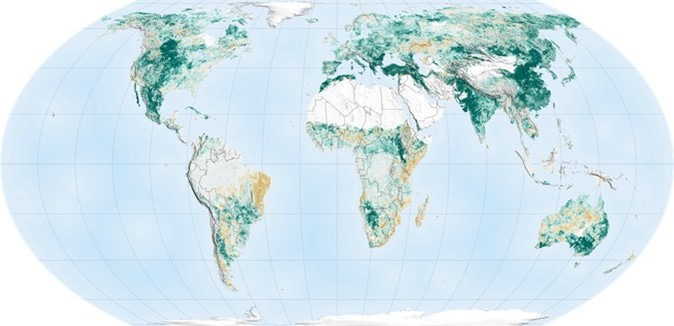

The article noted a study by Ranga Myneni, a remote-sensing specialist at Boston University. He teamed up with 32 other scientists in eight countries to study the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) satellite images to examine vegetation trends. The study concluded that since 1980, 25% to 50% of the world’s vegetated areas showed an increase in their leaf area index. That is a standard measure of vegetation abundance.

Myneni’s subsequent research pointed out that 70% of the increased vegetation could be attributed to increased CO2 fertilization. His research was substantiated by a 2021 study at the University of California, Berkeley that examined the rate of photosynthesis in various ecosystems worldwide. The study used “flux towers” that measure the exchange of gases between vegetation and the air above. Trevor Keenan, a carbon-cycle researcher, and other participants concluded that since 1982 there had been a 13% increase in photosynthesis driven by CO2 fertilization.

The world is growing greener rather than browner because of CO2.

Joshua Stevens of the NASA Earth Observatory noted that the green areas of the planet increased between 2000 and 2017, while the brown areas shrank. That should be good, right? Not quite.

Keenan observed that the extra CO2 was helping faster-growing plants slow the gas buildup in the atmosphere. “It’s not stopping climate change by any means, but it is helping us slow it down,” he said. The Paris Agreement was designed to slow down the rate of increase in temperatures by cutting the growth in CO2, or so we thought.

A 2023 study by Ziwei Liu, a hydrology modeler at Tsinghua University in Beijing, concluded that because of the impact of CO2 fertilization on aridity (the amount of moisture in the soil), desert areas will expand by only 5% by the end of this century, while vegetation productivity will increase green regions by about 50%.

A new study last month by three scientists at the University of New South Wales in Australia found similar conclusions. Their detailed modeling results “show continued increases in aridity due to climate change,” but “less than 4 percent of dryland areas [will] desertify.” While the exact extent of future greening will depend on the amount of CO2 accumulation in the atmosphere, under all the scenarios modeled, most drylands become greener.

The evidence of the greening from CO2 fertilization is becoming irrefutable. A study by Sami Rifai of the University of Adelaide examines the eastern Australian woodlands, which have experienced “repeated record-breaking droughts and heat waves” over the last 40 years. However, because of the increased CO2 fertilization, the greening of their woody ecosystems has overtaken the growing aridity from climate change.

Other regions where greening has been observed and studied include the Sahel region of the southern fringes of the Sahara Desert. Vegetation has benefited from the increased CO2 fertilization, but other natural cycles have also contributed. After the droughts of the 1970s and 1980s, rain has returned. Additionally, farmers have changed how they farm the land which has helped the natural regeneration of trees in their fields that provide shade and increased crop nutrients.

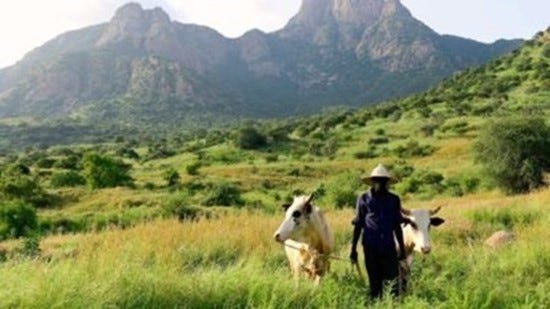

The mountains of Chad show how greening is at work and the opportunities it offers the people living there.

Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

The Guera Mountains in southern Chad, a region that has grown greener in recent decades, lie south of the Sahara Desert. The mountains are shown in the picture. This is an example of greening changing a region and opening up new agricultural opportunities.

Similarly, a World Resources Institute study that tracked Niger farmers showed that formerly treeless land in the south of the country now boasts about 200 million more trees across 12.5 million acres of land. More trees are good we were always led to believe.

What Is Good Could Be Bad

However, geographer Chris Reij of the World Resources Institute points out that “If CO2 fertilization was the determining factor in regreening here, it would happen everywhere in a region, but it does not.” He noted that the Niger greening stops at the border with Nigeria where farmers have little interest in nurturing trees. This dichotomy is cited as an argument against the science of CO2 fertilization.

Maybe the issue is education. Nigerian farmers may only need to be encouraged to make modest changes in how they farm their land to spur regreening. Nature seldom adheres to land borders, so to claim otherwise, as implied by Reij’s statement, suggests other factors are at work countering nature’s handiwork.

Another CO2 fertilization scientist seconds our observation. He told the Yale Environmental 360 paper’s author that the exceptional greening in Niger is probably also tied to farmer regeneration of trees. He pointed to Indian farmers also playing an important role in regreening areas of India. Again, it is a tribute to the impact of increased education of farmers about techniques that can improve the quality of their land by capitalizing on the benefits of CO2 fertilization.

Another attempt to put a negative twist on the regreening from CO2 fertilization is the claim there is a shift in the plants moving into the deserts and drylands at the expense of the “native” plants. Some climate scientists suggest that the impression of greening is an ecological breakdown because shorter shrubs, better able to adapt to less rainfall and higher temperatures, are overtaking the land.

Additionally, it was pointed out that four years ago, brushfires consumed an area in southeast Australia the size of South Carolina. Foresters blamed the fires on the combination of drought, high temperatures, and an accumulation of combustible woody vegetation due to CO2 fertilization. This argument seems to be from scientists wrestling with their theories challenged by a new scientific explanation of why drylands and deserts are turning green.

We guess Australian officials ignored the greening of the land because they were wedded to the climate change science that said the land could only get browner with more CO2. They therefore ignored the best practices in land management for preventing wildfires. This was like the U.S. and Canadian forest management officials who ignored historically sound forest management practices such as allowing logging of dead and dying trees, clearing underbrush, and periodic controlled burns, which contributed to the rash of forest fires in recent years.

Fred Pearce, the author of the Yale Environmental 360 article, wrote in his concluding paragraph:

“The world was wrong to expect that climate change would trigger rapid and widespread desertification in the world’s arid lands. In fact, the reverse is happening. But it could be a similar folly to imagine that the dramatic greening now visible in satellite images across many of those same regions is a reason to declare their troubles over.”

Maybe Pearce should stop looking for black clouds on a sunny day. He should be more concerned with the scientists who cannot grasp that maybe their settled science isn’t so settled. These scientists should acknowledge the good that comes with the message that they should revamp their scientific claims.

The greening of deserts has multiple positive impacts on the world’s population. It is slowing the growth of CO2 in the atmosphere, something that could be accelerated if better farming and land use management practices were embraced. The Niger and Nigerian greening difference is a case in point.

We should be challenging our agricultural specialists. New food crops that capitalize on CO2 fertilization could be developed to increase the world’s food supply. More food crops, especially near large low-income populations, could deliver huge human benefits.

Another Greening Example

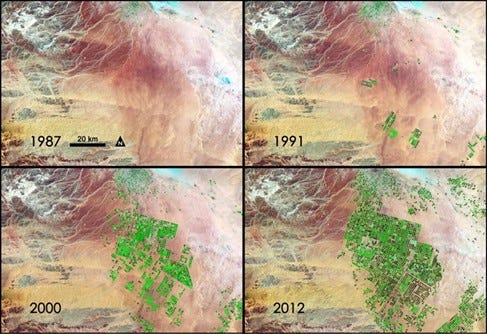

A series of NASA climate photos show an interesting progression of greening in the deserts of Saudi Arabia. This is an example of how powerful greening is since the four photos cover 25 years. We are not suggesting that in another 25 or 50 years Saudi Arabia will look like the Amazon or even the plains of North America. However, in that period, we can conceive that some food crops may be developed that will thrive and ease global hunger. Such a development could enable Saudi Arabia to diversify its economy, making it less dependent on hydrocarbon.

A 25-year history of the Greening of the deserts of Saudi Arabia shows the power of this force.

Climate.nasa.gov

Improving the fertility of the lands of Africa could work wonders for living standards on that continent. Fewer people suffering from malnutrition would dramatically benefit global living and health standards. It is also possible that the greening could slow the increase in CO2 even more than it has to date. More green plants suck up the CO2 from the atmosphere. That would be a global positive development, yet another nail in climate change science.

When the facts and the science change, scientists and policymakers should embrace the change rather than ignore or discredit it. More sinister are those scientists seeking to discredit the new facts. Scientists who question the settled science or point to alternative theories about CO2’s role in the climate routinely are labeled “climate deniers” when they are engaged in the scientific method by exploring the theories underlying a scientific belief. Greening from CO2 fertilization should be welcomed, even if scientists must give up their old science and embrace the new science.

I am actually in SEA. We get back the second week in September and head to Texas the following week. We need to get back to see our great grandson who was born a few weeks ago.

Good article, Allen. Are you still in RI? When do you head south? Be well and safe.