Energy Musings - August 26, 2024

A survey by AAA Northeast caused distress among EV proponents but its findings are confirmed by the PEW Research survey. Only 3 in 10 Americans, or less than half in the AAA survey want an EV.

More Bad News For The Electric Vehicle Market

We are told the electric vehicle (EV) revolution is successful. Some will point to EV registrations in June outpacing the rest of the light-vehicle market and reaching 8.9% of sales, but the growth was achieved with more model choices and heavy discounts. For EV cheerleaders, sales are advancing. But EV manufacturers continue to lose money, cut their future manufacturing plans, and are emphasizing plug-in and regular hybrid vehicles instead. For some car manufacturers, hybrid models are vastly outselling their EVs.

The problem with all the EV hype is that the sales growth is falling below the expected trajectory. Growth has been supported by price cuts and margin contraction. Auto manufacturers are adjusting their output plans confirming the current market softness, a trend the industry sees continuing well into the future.

A recent survey conducted by AAA Northeast of their members in Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey showed more than half the respondents never plan to buy a fully electric vehicle. Additionally, nearly half said they would not consider a plug-in hybrid. The survey results were in an article in The Providence Journal, only days after Rhode Island Governor Daniel McKee announced a new program to subsidize the installation of home EV charging stations to help boost sales. EVs are a key component of the state’s clean energy mandate that requires all new car sales in 2035 to be EVs. Rhode Island is one of nine states with a 2035 ban on internal combustion engine vehicle sales, following California’s lead.

Not surprisingly, an AAA official said the disinterest in EVs was fear of the unknown. Drivers indicated they feared being able to drive them, while also worried about charging them. Better education is supposed to be the solution. If that is true, then why are governments throwing even more money to lure buyers?

Jillian Young, director of public relations for AAA Northeast said, “What’s interesting is that this is an area of the country with an above-average market share of electric vehicles and we’re still seeing this resistance.” Did she consider this is also a part of the country with a high percentage of virtue-signaling elites? Those were the early buyers of EVs, only to have seen their values fall like a rock during the last 18 months.

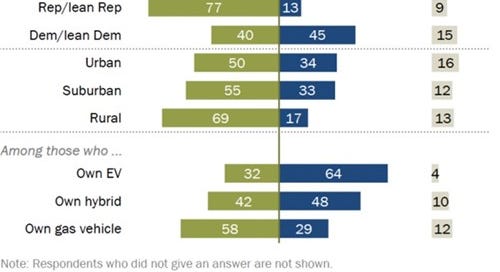

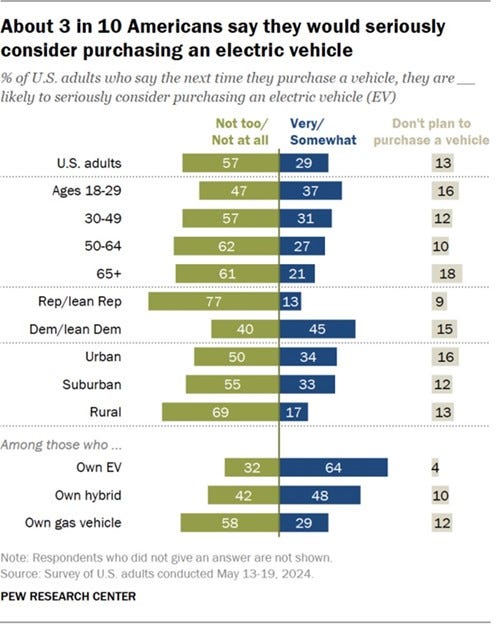

Ms. Young should rejoice at her survey’s results. The AAA Northeast survey showed 44% of respondents said they expect to buy an EV at some point. That share is better than the June Pew Research Center national survey that showed only three in ten Americans saying they would very or somewhat seriously consider purchasing an EV. That result is down nine percentage points in the past year.

The Pew survey results provide interesting reading. The interest in EVs decreases as people age. It is also interesting to see the political split, although Democratic enthusiasm and Republican dismissiveness are unsurprising. Likewise, the interest in EVs is highest in urban areas where people drive shorter distances so they do not suffer from “range anxiety” as much as suburban drivers, and certainly not as much as rural drivers.

Pew Research’s survey of Americans shows they are less interested in buying an EV than the AAA Northeast survey found.

We were also struck by the 32% of EV owners not interested in buying another one. Those owners of hybrid vehicles seem to be almost evenly split between EV buyers and non-buyers. Owners of gas vehicles seem to be wedded to them.

The rural market will be a huge challenge for EVs. Studies have shown that it is almost impossible for a public charging station to be profitable, let alone even recover its cost, because of the lack of vehicles that will pay to charge their EVs.

That is why we were interested in Rhode Island’s new subsidy program for home chargers. Like many government subsidies, it favors upper-income households. You have to own a single-family home, townhome, or condominium. The people in that segment not only have more income and can afford expensive EVs and costly home charging stations, but they also pay income taxes so that they benefit from tax credits for renewable investments.

You need to own a home to install a home charging station. Not all families in Rhode Island are in that situation. Only 62% of homes are owner-occupied according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau. The state’s food bank network provides food to 80,000 people a month, 8% of the state’s population. Eleven percent of the state’s population is below the poverty income line. For a large share of Rhode Island’s population, they cannot use EV tax credits. For this segment of the population, they cannot afford EVs.

EV owners who do not own a house must rely on public charging stations. They are more expensive to use and for the power purchased than an EV owner using a home charging station.

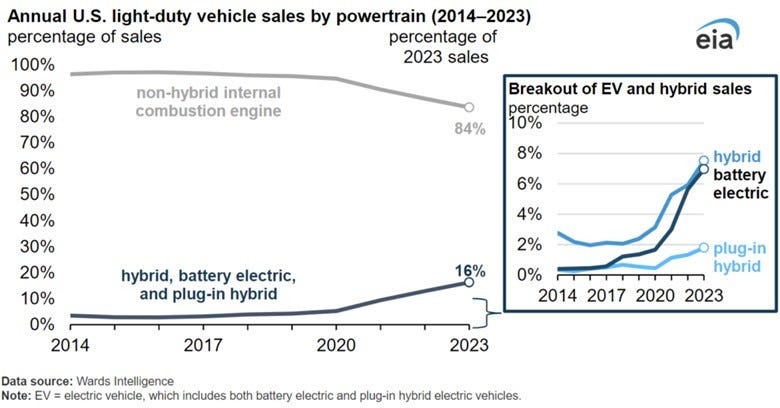

A problem when discussing EVs is their definition. When the EV revolution began, the definition and market forecasts were based on battery electric vehicles (BEV). EVs were associated with the early Tesla BEV model successes. In recent years, plug-in hybrids (PHEV) have become an EV option and the definition was adjusted to include both BEVs and PHEVs. The definition has been further expanded to encompass regular hybrid vehicles that employ EV batteries along with an internal combustion engine. Therefore, the numbers of EVs and their market shares vary depending on the specific EV definition used. When you read an article, be wary when they use the term EV, because you often do not know whether it describes the fleet narrowly or expansively. This could distort the analysis if the historical data cited is not comparable to the current definition.

A chart from the Energy Information Administration shows these definitional differences in the right-hand chart. Each component of the most expansive fleet definition is identified. Therefore, when you look at the market shares in the larger chart, it compares ICE vehicles to all EVs.

When we examine the market shares by sales by vehicle type, in 2023, traditional hybrids outsold BEVs. When you add PHEVs and hybrids, their market share exceeds BEVs’ share by nearly 40%. Based on sales data in 2024, we expect the gap will widen further.

The EIA EV market analysis highlights the popularity of hybrid vehicles compared to BEVs and PHEVs.

The definitional issue arose when reading The Providence Journal article on the AAA Northeast survey. The writer mentioned that “as of July 1, there are 12,272 electric vehicles in Rhode Island, according to the state Department of Environmental Management.” We assume the number comes from the state’s vehicle registration data. Based on the 338,351 automobiles registered in Rhode Island as of 2021 (latest data available from the Department of Motor Vehicles national database), EVs represent a 3.6% share. However, in Rhode Island, the state gives nice green and white license plates that say electric vehicle upon renewal starting this year. However, we have observed that these plates are given to all EV categories.

When we checked Rhode Island EV registration data maintained by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) with assistance from Experian Information Solutions, the 2023 data listed 5,934 all-electric vehicles (BEVs), or 48% of the figure claimed in the AAA Northeast article. This total equates to a 1.8% share of Rhode Island’s registered automobiles.

The NREL database was last updated in June. Interestingly, Rhode Island only exceeded the registered EVs in Montana. There were five states – Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wyoming – with no registered EVs. In these states, we suspect hybrid vehicles that are counted as EVs in some market assessments.

The AAA Northeast survey signals that the conversion to an EV fleet is happening very slowly. It is happening more slowly than auto manufacturers planned and invested in, so they are scrambling to cut their losses by not building as many EVs and producing the types of vehicles customers want. The EV revolution is stalling.