Energy Musings - April 5, 2024

The first hurricane forecast for 2024 expects a "very active" summer season. The Colorado State University team forecasts 23 named storms with 11 becoming hurricanes and 5 major storms.

CSU Hurricane Forecast A Warning For Energy

April is too early for most people to pay attention to hurricane forecasts for this summer. Heck, the Northeast is recovering from a stronger-than-normal Nor’easter that dumped double-digit amounts of snow across the upper regions of New England. While snow in Maine in April is not unusual, double-digit amounts are.

The start of April every year brings the initial Atlantic tropical storm forecast from the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University. The forecasting began in 1984 under Professor Emeritus Bill Gray and continued until he died in 2016. It is produced now under the direction of meteorologist Phil Klotzbach, who studied under Gray.

The CSU team’s April 4 forecast calls for the 2024 Atlantic basin to be “extremely active.” Record-warm tropical and eastern subtropical Atlantic sea temperatures drive the forecast. The CSU team forecasts 23 named storms in 2024, with 11 reaching hurricane strength and five becoming major hurricanes. The table shows the details of the CSU forecast and how many more storms, hurricanes, major hurricane, and their respective days are expected compared to the averages for 1991-2020.

There will be more named storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes as well as many more associated days of storm activity.

April tropical storm forecasts began in 1995, and the outlook “historically has the lowest level of skill of CSU’s operational seasonal hurricane forecasts.” The lower skill level is due to the “considerable changes that can occur in the atmosphere-ocean between April and the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season from August-October.”

The press release announcing the forecast mentioned that that the warm waters and likely development of a La Niña has given the CSU team “higher-than-normal confidence” in its prediction. It noted this was the highest hurricane prediction the CSU team had issued in April. The previous high hurricane number (9) was issued several times.

What drives the higher tropical storm forecast? The CSU team points out that when the Atlantic has warmer-than-normal sea temperatures in the spring, it leads to weaker winds blowing across the Atlantic basin, which helps keep the temperatures higher into the peak of the hurricane season. A warm Atlantic basin leads to lower atmospheric pressure and a more unstable atmosphere, which favors more hurricanes.

Many people are unaware of the connection between weather and atmospheric conditions in the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic hurricane activity. At the moment, the tropical Pacific is influenced by El Niño conditions. The Pacific expects to transition to La Niña conditions by the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season. La Niña tends to decrease upper-level westerly winds across the Caribbean and into the tropical Atlantic basin. These lower upper-level winds reduce vertical wind shear that often inhibits the development and strengthening of Atlantic basin tropical storms.

La Niña is expected to develop. Its timing, strength, and even failure to develop could materially alter the hurricane forecast. That is why the April forecast has the lowest skill level of any of the four seasonal forecasts CSU issues each year. However, the CSU team points out that the 2024 hurricane season is exhibiting characteristics similar to the 1878, 1926, 1998, 2010, and 2020 seasons - all very active Atlantic hurricane seasons. That is why the CSU team has “somewhat lower levels of uncertainty” than other April forecasts.

Regardless, the CSU team warns: “It takes only one storm near you to make this an active season for you.”

Going back to Bill Gray’s final years overseeing hurricane forecasting, the CSU team has worked to perfect a model estimating the probability of where a major hurricane might make landfall. Major hurricanes are Category 3, 4, or 5. All major hurricanes have wind speeds above 110 miles per hour and scale upward. As wind speed increases structural damage grows. So, too, will the water that is pushed ahead by storm surge. Predicting the coastal landing point and surrounding region of exposure helps people prepare to weather the storm or to evacuate, thereby minimizing damage and possible loss of life. This knowledge is critical for public safety officials, utilities, and insurance companies.

The probability of a major hurricane making landfall along the entire U.S. coastline is 62% compared to the historical average for 1880-2020 of 43%. The East Coast probability is 34% (21% historical average). The Gulf Coast probability is 42% (27%) and the Caribbean probability is 66% (47%). All these probabilities are nearly 50% greater than their historical averages.

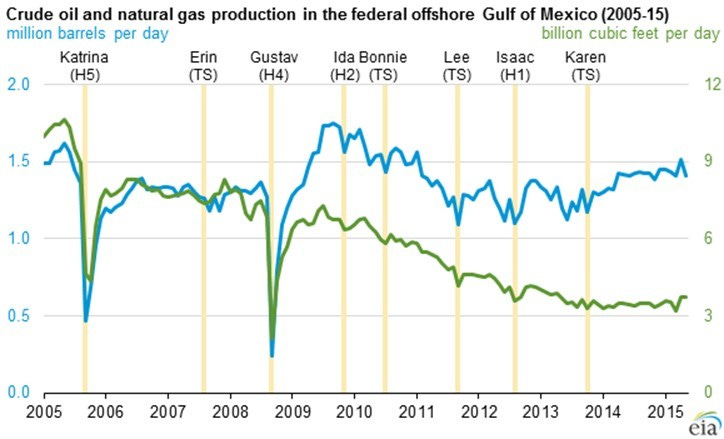

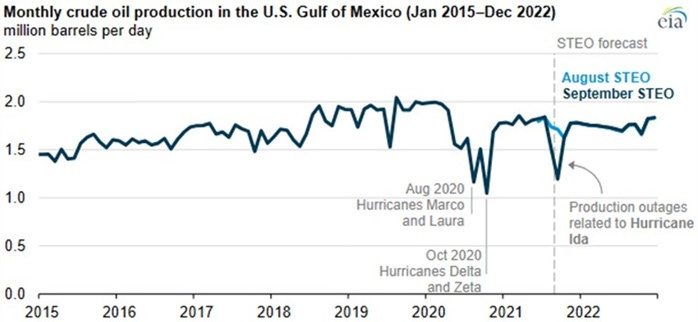

The Gulf Coast probability is critical for energy. While some hurricanes transit the Gulf of Mexico and make landfall in Mexico, Central America, or even northern countries of South America, the storms often force oil and gas production to be shut down. Besides the temporary loss of petroleum output, the production facilities - offshore platforms, pipelines, refineries, and petrochemical plants - can also be impacted. The following charts show Gulf of Mexico oil and natural gas production for 2005-2022. They show how much output was impacted by the various hurricanes.

The history of GoM oil and gas output impacted by hurricanes shows varying degrees of damage.

Hurricane Ida was extremely devastating for the Gulf Coast petroleum industry.

One of the most damaging hurricanes was Ida in August 2021. It forced the shutdown of 96% of the Gulf of Mexico’s crude oil output and 94% of its natural gas production. Nine refineries were shut down or forced to reduce operations. The loss of power along the Gulf Coast also complicated the recovery effort as pumps to empty areas surrounding refineries and petrochemical plants were inoperable for days. Even major petroleum product pipelines moving refined products from the Gulf Coast to the Southeast were forced to shut down for days causing gasoline and diesel shortages and associated pump price spikes.

LNG terminals were damaged. Therefore, LNG tankers were unable to load cargo. Damaged offshore pipelines leaked oil that needed to be stopped. These problems had to be managed despite the severe coastal damage to infrastructure and power that impacted people and assets needed to deal with the problems.

We are not saying that the very active hurricane season forecast by CSU will cause oil and gas shortages. There have been active hurricane seasons when no major hurricanes made landfall. However, even marginal hurricanes can inflict petroleum industry damage, or at least force the shut-in of output for days. These are risks that the domestic petroleum industry has dealt with for decades and managed well throughout history. The possibility of hurricane disruptions will begin to impact daily oil prices when the first storm of the season emerges, even if it is off the coast of Africa and days away from the Gulf of Mexico. Be prepared and buckle up.

Looking forward to see how the thousands of planned ocean wind turbines planned off the Atlantic Coast survive the hurricanes.