Energy Musings - April 28, 2025

BP faces an uncertain future as the failures of strategy moves and corporate governance continue to hinder its share price from recovering. History may offer a guide to the future.

BP Surfed The Wave Until It Wiped Out

Like all great surfers, finding the perfect wave is challenging, but riding it is glorious. It can be a spectacular ride and often a soft landing as the wave crests and the surfer slowly descends. But other times, it can end in a crash as the wave overwhelms the surfer. This century has demonstrated these truths for BP shareholders. The wave has overwhelmed long-time shareholders who have seen their early gains from the perfect wave wiped out. They are now wondering what the future holds.

We are describing BP’s green energy voyage, which began at the start of the millennium and continued through the tenure of its chief executive officers, starting with John Browne (now The Lord Browne of Madingly). The green energy voyage seems to have crashed with the “hard reset” engineered by CEO Murray Auchincloss.

Not everyone is happy with the recent strategic adjustment. They are focused on the company’s caving to the demands of activist investor Elliott Investment Management. Their focus is further stirred by the news that BP’s chairman, Helge Lund, plans to retire sometime in 2026. This will set up another interesting management change and a read on BP’s corporate governance.

Multiple interviews and newspaper articles crystallized our interest in revisiting the last 25 years of BP’s history, leadership, and governance issues. BP actively restructured the global oil industry at the end of the 1990s. The wave of industry consolidation shrunk the number of major international oil companies and created the current handful of super-majors. However, BP’s embrace of renewable energy captured investor attention and drove its share up.

Lord Browne headed BP from 1995 to 2007. When he was elevated (the CEO and chairmanship roles had been previously separated), Browne acknowledged that BP was behind industry leaders Exxon and Shell. He described BP as “too small to prosper.” That was despite BP’s involvement in Alaska's giant Prudhoe Bay field through its ownership in Standard Oil of Ohio. Browne played a role in the discovery, as Alaska was his initial assignment when he joined BP.

During his leadership of BP, a period described by the Globe and Mail as the company’s “golden period of expansion and diversification,” he engineered mergers with industry rivals Amoco in 1998, Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) in 1999, Burmah Castrol in 2000, and Veba in 2001. His initial deal set off a massive global industry consolidation. Furthermore, Browne helped BP gain access to Russian oil reserves by creating the joint venture TNK-BP. BP evolved into a global energy heavyweight from a company with little direction and subject to the vagaries of Middle East oil politics.

While a successful oil executive, Browne maintained an active interest in the arts and got BP to sponsor numerous theatrical endeavors. “A renaissance man, the Sun King of the oil industry” was the view of Browne, according to an American oilman. The Financial Times noted, “the remark is double-edged, a tribute to the breadth of Browne’s interests outside the oil industry - but also a warning about the risk of a monarchy developing at BP as the Browne myth grows.”

While many overlook Browne’s success in building a global oil powerhouse, one no longer dependent on the volatile Middle East, he also helped kick off the industry’s commitment to improving the environment, and in a seminal speech at Stanford University in 1997, dealt with the global climate. The speech sent shock waves throughout the oil industry.

He spoke of a “discernible human influence on the climate,” a “link between the concentration of carbon dioxide and the increase in the temperature,” and a “need for action and solutions.” He told the audience that BP would be taking steps to control its emissions, fund scientific research, invest in the development of alternative fuels, and contribute to public policy debates on solutions to the problem. Browne said BP’s efforts would go beyond the regulatory requirements. His comments came as other industry leaders rebelled against environmental regulation and questioned the science.

That speech set Browne on a course to reinvent BP in 2000 as “Beyond Petroleum.” The strategy included a new green sunflower logo signifying that BP was moving away from oil and gas. According to Browne, the new logo and slogan “tested very well, so we said, ‘OK, let’s use it.’ But it was not meant to be taken literally that we were going to get out of petroleum.” The Beyond Petroleum move caught the growing environmental movement, leading to a soaring BP share price. Over the decade of 1997-2007, BP’s share price climbed 150% while the S&P 500 rose just 43%. Browne and his team were convinced they had struck gold.

Browne acknowledged in an interview with the FT that at the time, “it was unclear if you could make money [with renewables].” With the effort focused on getting the risk/return metrics right for the barely profitable renewables, BP was bitten by accidents in its core business. In 2005, an explosion at BP’s Texas City refinery killed 15 people. An oil spill occurred in Alaska the following year, putting a blemish on the company’s environmental record. These accidents set in motion the end of Browne’s tenure at the helm of BP.

BP’s logo highlighted Lord Browne's Beyond Petroleum effort.

Tony Hayward, a geologist who had risen through the E&P ranks at BP, had been identified by Browne as an up-and-coming executive in 1990. Browne made Hayward his executive assistant. In 1992, Hayward moved to Colombia as exploration manager. He then headed up the company’s Venezuelan operations, before returning to London as the director of BP Exploration. In 2000, he was appointed BP group treasurer. In 2002, he was elevated to an executive vice-president role and then chief executive of exploration and production.

Browne was expected to retire in 2008 when he turned 60, the mandatory retirement age at BP. However, the Texas City and Alaska accidents spurred BP’s non-executive chairman, Peter Sutherland, to accelerate the process for finding a replacement for Browne. Safety and production issues drove the process. It was a three-way contest between Hayward, Bob Dudley, CEO of TNK-BP, and John Manzoni, head of BP’s marketing and refining.

At an internal management meeting in late 2006, Hayward criticized BP management. He told a town hall meeting in Houston, “We have a leadership style that is too directive and doesn’t listen sufficiently well. The top of the organization doesn’t listen to what the bottom is saying.” In January 2007, Hayward was announced as Browne’s successor. He was appointed BP’s CEO on May 1, 2007, immediately after Browne resigned due to the fallout from a personal legal dispute with the Daily Mail. He sought an injunction against the paper, preventing it from publishing allegations about his personal life. However, Browne lied to the court during the legal proceedings about how he met a former partner. After his court defeat, the Daily Mail outed Browne as gay, forcing him to resign from BP.

While Hayward’s tenure progressed smoothly, it wasn’t apparent to the outside that he was willing to tolerate more risk in BP’s exploration and development operations. That risk contributed to the April 20, 2010, explosion on the Deepwater Horizon semi-submersible drilling rig working offshore Louisiana. Not only were 11 people killed, but the explosion and fire caused a massive oil spill, which would eventually become the industry’s largest oil spill ever.

Hayward’s comments and actions following the accident began his undoing. The environmental impact of the Gulf spill would likely be “very, very modest,” he told the media, and he called the spill “relatively tiny” in comparison to the size of the ocean.

He told a Louisiana reporter, “We're sorry for the massive disruption it’s caused to their [residents] lives. There’s no one who wants this thing over more than I do, I’d like my life back.” Critics mocked his statement. Hayward also suffered through a contentious and disastrous congressional hearing in June 2010. The PR missteps continued, and the stress became evident.

The day after the hearing, the chairman of BP announced that Hayward would step away from daily involvement in the company’s efforts to stop the spill and its clean-up efforts. American and Mississippi native Bob Dudley was put in charge of handling the oil spill. A month later, Dudley was announced as Hayward’s replacement effective October 1, 2010.

Dudley was charged with saving BP. His first tasks were verifying the safety of BP’s operations worldwide, restoring the environment of the Gulf Coast, and securing the company’s finances. Money was needed to meet the oil spill’s costs and legal claims. This forced Dudley to restructure the company – the number of BP-operated upstream installations was cut by half, the number of wells by a third, but only about 10% of BP’s oil and gas reserves were sold. Dudley’s “value over volume” approach drove the three-year effort. While his efforts saved BP, the debt from the oil spill still weighs on the company’s finances.

He also used the Deepwater Horizon disaster as the catalyst to change BP’s culture. He installed a new set of values, with safety being the most prominent. BP became more open, and Dudley encouraged leaders to “listen to the quietest voice in the room.”

Dudley was also able to broker a deal to sell BP’s interest in TNK-BP for a significant infusion of cash and a 19.75% stake in Russian oil giant Rosneft. The cash helped with the oil spill expenses. The deal also simplified BP’s management issues in dealing with the Russian joint venture.

Just as it seemed BP’s situation was stabilizing, Dudley and the entire international oil industry were upended by Saudi Arabia launching an oil price war that sent prices down from $115 a barrel in mid-2014 to $27 in January 2016. Profitability went out the window. Dudley became famous for his observation that the industry would have to learn to manage with oil prices “lower for longer.”

The industry devastation from the oil price war set the stage for its leaders to embrace the demands of investors for “financial discipline” and abandon growth for growth’s sake and return excess cash to shareholders in the form of dividends and share repurchases. This discipline continues to guide the industry today as oil prices slide due to President Donald Trump’s tariff warfare.

As Dudley guided BP through the financial peril from the Gulf oil spill and the industry oil price war, environmentalism emerged as a significant social issue. Lord Browne’s comments about climate change and the role of fossil fuels seemed to be coming true. The anti-fossil fuel movement grew powerful in Europe, but less so in America. The movement played a role in the selection of Dudley’s successor.

In 2019, Helge Lund was appointed chair of BP. The former Statoil and BP Group chief executive promised to oversee two transitions: BP’s appointment of a new CEO, and a shift to become a global energy company rather than an oil and gas major. In BP’s 2019 annual report, Lund wrote, “We enter a new decade with a new company purpose: to reimagine energy for people and our planet.”

According to former senior BP executives, the board believed there was a case for building a leading position in the energy transition. It was worried about being left behind as competitors “scooped up subsidies and flows of money from investors allocating capital according to environmental, social, and governance criteria,” wrote the FT.

For a company whose share price has been treading water for years, the vision appeared as a guiding light for a better future for BP. Once again, a three-man competition for replacing Dudley was conducted. The three men were asked to set out their vision for BP. Bernard Looney, the head of BP’s oil and gas production, set forth a view of the company leading the energy transition. Another executive was skeptical, while the third competitor was in the middle.

Looney was chosen and stepped into the CEO’s position in January 2020. He assembled his team and, in February, presented BP’s green energy plan. It included goals such as building 50 gigawatts of wind and solar generating capacity, which could supply all the UK’s energy needs. More significant was the aggressive plan to cut oil and gas production by 40% by 2030. At the same time, BP would ramp up its green energy spending, reaching a tenfold increase by 2030. Looney did warn BP pensioners at the February presentation that they should no longer expect dividend increases as they had received in the past because the profitability of renewables was lower than that of oil and gas, but over time, things would improve.

Looney’s vision was lauded when the Covid-19 pandemic forced economic shutdowns that destroyed oil and gas demand, briefly sending oil prices into negative territory in the spring of 2020. Government responses to the pandemic launched a significant wave of inflation globally. That forced central banks to raise interest rates, killing the economics of renewable energy projects dependent on cheap money. In September, when Looney presented his detailed plan to investors, BP’s share price dropped more than that of other international oil majors as investors questioned its feasibility. The plan was further upended when Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022.

Looney’s departure from BP in September 2023 was sudden. In the spring of 2023, the board was made aware of questions about Looney’s relationship with former colleagues that he had failed to disclose when being selected as CEO. After Looney detailed the relationships and promised no others, the board was presented with new allegations. Looney’s misleading the board doomed his tenure as CEO. Once again, BP leadership was thrown into turmoil.

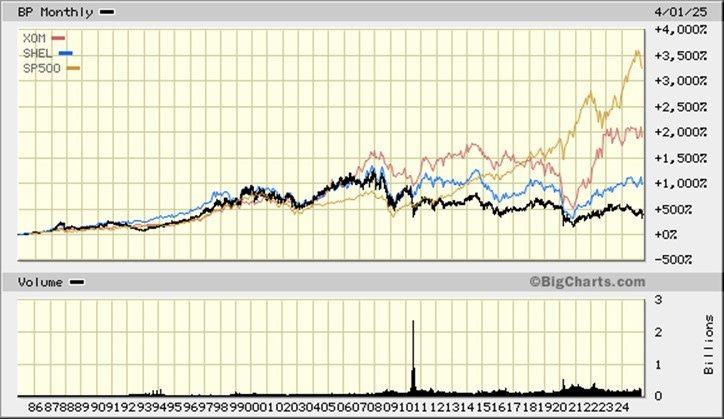

The company diligently searched for a new CEO and settled on Murray Auchincloss, BP’s CFO and long-time Looney lieutenant. Auchincloss, a long-time employee, took nearly a year to develop a new business plan. BP’s quarterly results and share price underperformed its primary competitors during that time. The long-term BP stock price chart shows how badly BP has performed in recent years compared to ExxonMobil, Shell, and the S&P 500 index.

BP’s new plan is to refocus on oil and gas, but the company has underinvested in its resources for five years. The company still has $50 billion of debt (mainly from the Deepwater Horizon disaster) and needs higher oil prices to generate cash. Auchincloss promised shareholders at BP’s recent annual meeting that he was only thinking about four things: cash flow, operating costs, debt levels, and generating higher returns. He previously told the public he was keeping his options open on renewable energy investments. Thinking and generating results are often different things. How patient will investors be after years of lagging investment returns?

BP’s long-term share price record is not positive.

With activist shareholder Elliott Investment Management agitating for a more aggressive plan to increase the value of BP’s shares, Auchincloss is under pressure to deliver better earnings performance soon. Given lower oil prices, it may be a challenge. Reducing the company’s debt would demonstrate progress, but it would be a tough move in today’s energy market.

The huge valuation gap between BP shares and its leading competitors is hanging over any step Auchincloss might take. BP has a debt-to-total capital ratio of 35% compared to ExxonMobil and Chevron’s average of 19%. BP is trading at an EV-to-EBITDA (enterprise value to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) multiple of 4.9x, while its peers average 5.8x. This valuation gap and activist shareholders have sparked renewed speculation that BP is a takeover candidate. With a market cap of roughly $100 billion, less than a third of ExxonMobil’s $371 billion and half of Chevron’s $190 billion and Shell’s $204 billion market caps, it is conceivable one of these giants would be interested in BP’s assets.

Auchincloss’s tenure at the helm of BP may become as consequential as his CEO predecessors but for a different reason. The “sticky wicket” for Auchincloss results from questionable corporate governance at BP in recent years. Lund’s tenure during this time is proving controversial. He has acknowledged mistakes. However, investors wonder if Lund has merely replicated mistakes he made when running Statoil. The company, now Equinor, has booked tens of billions of losses on investments made during Lund’s tenure as the company rushed to join the fracking revolution in the United States. Lund admitted Statoil “invested too much and bought at too high prices” and “took too much risk.” Lund has offered similar explanations for the problems BP has been dealing with in recent years. His announcement of plans to leave in 2026 did not prevent 25% of shareholders from voting against his reappointment to the BP board.

The past may provide a study in mistakes made, but history cannot be changed. A radical strategy reset by Auchincloss may be the only alternative for BP to remain independent. Will Auchincloss demonstrate the leadership skills of Lord Browne and Bob Dudley, or the mistakes of Hayward and Looney? Only time will tell, and time may be short.

Good job, Allen,