Energy Musings - April 14, 2025

The debate over whether there is an energy transition continues. We were shocked to see a vocal and long-standing proponent of the transition acknowledging it isn't happening and why.

Why There Is No Energy Transition

A BloombergNEF email promoting the BNEF Summit New York in April asked, “The Energy Transition in 2025: Moving Forward or Falling Behind?” That might be a good question if you believe there is an energy transition. However, in BP plc’s Energy Outlook last year, chief economist Spencer Dale wrote of the most significant challenge facing the world’s energy system: “The world is in an ‘energy addition’ phase of the energy transition in which increasing amounts of low carbon energy and fossil fuels are consumed. The challenge is to move – for the first time in history – to an ‘energy substitution’ phase, in which low carbon energy increases sufficiently quickly to allow the consumption of fossil fuels, and with that carbon emissions, to decline.”

The issue of ‘energy addition’ versus ‘energy transition’ has gained more notoriety lately with the publication of an essay in the March/April Foreign Affairs issue. “The Troubled Energy Transition – How to Find a Pragmatic Path Forward” was authored by Daniel Yergin, Peter Orszag, and Atul Arya. It concludes there is no “energy transition” but only “energy addition.” This counters the narrative that the substantial growth in renewable energy, which has occurred in recent years, will soon displace hydrocarbon energy in the world’s energy mix. The authors concluded their essay with the following.

“Today’s energy transition is meant to be fundamentally distinct from every previous energy transition: it is meant to be transformative rather than an additive. But so far it is ‘addition,’ not replacement. The scale and variety of the challenges associated with the transition mean that it will not proceed as many expect or in a linear way: it will be multidimensional, proceeding at different rates with a different mix of technologies and different priorities in different regions. That reflects the complexities of the energy system that underlies today’s global economy. It also makes clear that the process will unfold over a long period and that continuing investment in conventional energy will be a necessary part of the energy transition. A linear transition is not possible; instead, the transition will involve significant tradeoffs. The importance of also addressing economic growth, energy security, and energy access underscores the need to pursue a more pragmatic path.”

Energy analysts earlier recognized the reality that there was no energy transition. In the summer of 2022, Mark Mills wrote “The ‘Energy Transition’ Delusion: A Reality Reset,” which showed the failure of massive spending on renewable energy sources to push hydrocarbon fuels from the global energy stage. All the renewable energy spending contributed to higher inflation and increased energy insecurity. Other analysts have joined Mills in trying to move the energy future discussion to one based on realism.

We were intrigued to read recent issues of Cold Eye Earth, a subscription newsletter written by long-time West Coast-based energy writer Gregor Macdonald. We began reading his publication years ago when it was known as The Gregor Letter. Macdonald has been writing about and predicting an energy transition for years. In his February letter, we were surprised when he wrote, “The forward momentum of global energy transition has now stagnated, and the deployment of new energy technology has lapsed into becoming an additive rather than a transformative phenomenon.”

After years of tracking and predicting how electric vehicles would displace internal combustion engine vehicles and erase gasoline demand, the thesis has failed to develop. Based on the West Coast, Macdonald consistently reported the latest California data showing increases in renewable energy and how it would track the S-shaped acceptance curves of technology products, such as cell phone growth. So far, this transition has not yet occurred. While electric vehicles are cited for slowing gasoline consumption growth in the U.S., it is more likely that the government mandates for improved average fleet fuel economy are more responsible.

The following chart from the Environmental Protection Agency shows rising trends for vehicle miles per gallon (+106%), weight (+9%), and horsepower (+98%), but a 53% decline in CO2 emissions from 1975 to 2024. The ability to increase miles per gallon while building larger, heavier, and more powerful vehicles is a testament to the adoption of improved engine technology. Adopting catalytic converters, unleaded fuel, and more efficient engines also improved mileage while reducing CO2 emissions.

How vehicles have become less polluting.

The automobile industry is highly visible and has been an easy target for environmentalists. Improperly maintained internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles can emit more pollution than allowed. However, the idea that tailpipe-less electric vehicles (EVs) are the solution is disingenuous. Building EVs generates substantially more carbon emissions than a similar ICE vehicle, meaning they must be driven for years to offset their legacy CO2.

However, this transition has proven substantially more challenging than we were led to believe in the 2000s. The problem in transitioning the automobile sector is that people depend on their vehicles for everyday life and love the freedom to choose the type of vehicle they want that fits their needs. That option is being curtailed by government mandates to purchase EVs. Governments have facilitated the EV transition with substantial tax subsidies that favor wealthy buyers; however, the financial burden of these subsidies has become overly burdensome. Every withdrawal of EV subsidies leads to declining sales, showing their dependence on mandates and government handouts.

The U.S. government has worked out a loophole in its EV subsidy program to help stimulate sales. EVs must meet significant standards for sourcing components, which has made many popular models ineligible for buyer subsidies. However, declaring that every EV lease is a commercial vehicle and not restricted from subsidies has helped reduce EV costs and spurred sales.

Despite these efforts, Gallup recently reported a deterioration in EV interest among the public. While the percentage of people who already own, are seriously considering, or might consider buying an EV held steady with 2024’s interest at 51%, the total is down from 58% in 2023. The most eager supporters of EVs, those who own or are seriously considering purchasing one, have declined to 11% from 16% in 2023 and 2024.

Gallup’s poll showed that more Americans are interested in hybrid electric vehicles than EVs. Sixty-five percent of U.S. adults either own a hybrid electric vehicle, are seriously considering purchasing one, or are open to buying one in the future. More importantly, current hybrid ownership exceeds EV ownership (8% to 3%). And potential hybrid buyers exceed potential EV buyers by 57% to 48%.

This sentiment shift away from EVs creates a problem for the energy transition. It impacts the role electricity plays in the energy transition plans. “Electrify everything” is seen as a solution for cutting emissions from hydrocarbon-generated power. That’s because all the electricity is to be produced by renewable energy. The problem is it has not happened and is not likely to happen anytime in the future. This is where Macdonald has become a realist about our energy future. His analysis and explanations undercut the popular narrative of an energy transition. He summarized the narrative’s problem.

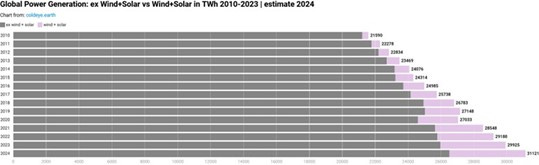

“The evolution of global power generation adheres to the Additive model of energy transition. In the Additive model, wind and solar maintain their fast and beautiful expansion, but wind up as a layer on top of legacy sources. This is in contrast to the Transformative model of energy transition, which looks at a chart like the one below and assumes that wind and solar will, after reliably taking 100% of annual marginal growth, get to work on the underlayer of incumbent energy sources in power, forcing them into decline. But there is no historical, nor economic justification for such a view. The Transformative model represents nothing more than the current consensus reality, shared by many climate observers.”

Energy realism upends energy transition predictions.

Macdonald wrote under the chart in his newsletter that Cold Eye Earth now believes in the Additive rather than the Transformative model. He cited four key points in support of this change. First, the Additive model does not conflict with continued growth in renewables. There is still a strong value proposition which gets more robust over time. Second, the Additive model aligns with energy history. Third, the Addition model reminds us that energy history shares the stage with economic history. The reality is that energy is tied to economic and population growth. Moreover, according to Macdonald, “Jevons was correct.” Making something more efficient leads to using more of it, which has been valid for energy throughout history.

Finally, Macdonald noted that the Additive model exposes the weaknesses of the Transformative model, which is propped up with unsupported assumptions and has no historical example. In his view (something he supported in the past), the Transformative model may have borrowed too many assumptions from new technologies' diffusion curves (S-curves). They are aligned with consumers who can afford to write down legacy products to zero when new, improved ones are introduced. That model doesn’t work for power plants.

Macdonald is now critical of those climate change proponents who hold up California as the glowing example of the success of the Transformative model. He writes:

“Yes, it’s nice that humans have built leading-edge states like California, dominated by knowledge work, creative design, and very little manufacturing. Emissions are in decline in California, unsurprisingly. Petrol consumption is in decline, natural gas consumption is in decline, and coal has been (nearly) zeroed out of the system. But that’s because the ideas, inventions, and products conceived of in California are manufactured elsewhere. One of the other pitfalls to the Transformative model, therefore, is that it treats states like California as a proof-of-concept that energy transition inexorably leads to actual decarbonization. Presumably, it’s not necessary to name the logic flaw in that view. But, if you insist: The Fallacy of Composition.” This same scenario can be applied to Germany, which has exported a significant amount of its manufacturing capacity. It has migrated to countries willing to accept higher emissions and have cheaper electricity and labor.

The problem Macdonald identifies with the Transformative model is the economic pain associated with its implementation. Politicians embracing the model for guiding energy policy have failed to address its weakness – “the burden of adjustment” – or they ignore the problem’s existence. Importantly, they are unwilling to determine who will bear the burden of shutting down economically viable power plants and vehicles because such answers are political suicide.

We identify their dilemma with the former Louisiana Senator Russell Long, long-time chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. He commented, “Most people have the same philosophy about taxes.” Their mantra is, “Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax that fellow behind the tree.” It is always easier for someone else to bear the burden and feel the pain. Socializing costs is another technique for solving the problem. However, everyone eventually pays the price.

Is there an energy transition? No. Why? Population and economic growth. More people and more GDP equals more power demand, which cannot be met with renewals. That inability means renewables can't displace legacy fossil fuel generation capacity. China is the best example. Environmentalists have praised China for its massive investment in wind and solar power. However, it also is aggressively adding to the world’s largest coal generation capacity.

Macdonald laments that “of all the systems we propose to decarbonize, the power system is the easiest to transform.” The power system is a network of wires that allows a new generation source to plug in easily as old sources exit. “So. what does it say that the easiest system to decarbonize continues to see fossil fuel growth?”

Until the failure to decarbonize the easiest system is corrected, the prospect of overcoming the challenges of decarbonizing more difficult sectors such as steel, cement, and other industrial processes is questionable. Do not point to states such as California, where the population is shrinking, as a role model for the energy transition. We want and need economic growth for everyone's benefit.

At the heart of the energy transition problem is that there is no agreement that the financial burden associated with the transition is worth the possible benefits. Most analyses of energy transitions only assess the economic, environmental, and health costs of increased carbon emissions. These costs are never weighed against the societal benefits of improved living standards and increased longevity from these legacy energy sources. Technological improvements in energy efficiency and cleanliness allow us to cut our emissions. However, this progress also suggests that seeing an energy transition happening soon is unrealistic until the financial burden issue is resolved and the public embraces its solution.